Guest Blog from Helen Lambert, Chair of Caversham and District Residents Association

This year marks the centenary of the opening of the new Reading Bridge. Although there had been one bridge at Caversham for over a thousand years, crossing the Thames further down at Lower Caversham was far from easy. It was not until after the boundary change in 1911 that a new modern style bridge in a new location was planned for Lower Caversham. Work was delayed by the outbreak of WWI and the new bridge opened on 3 October 1923.

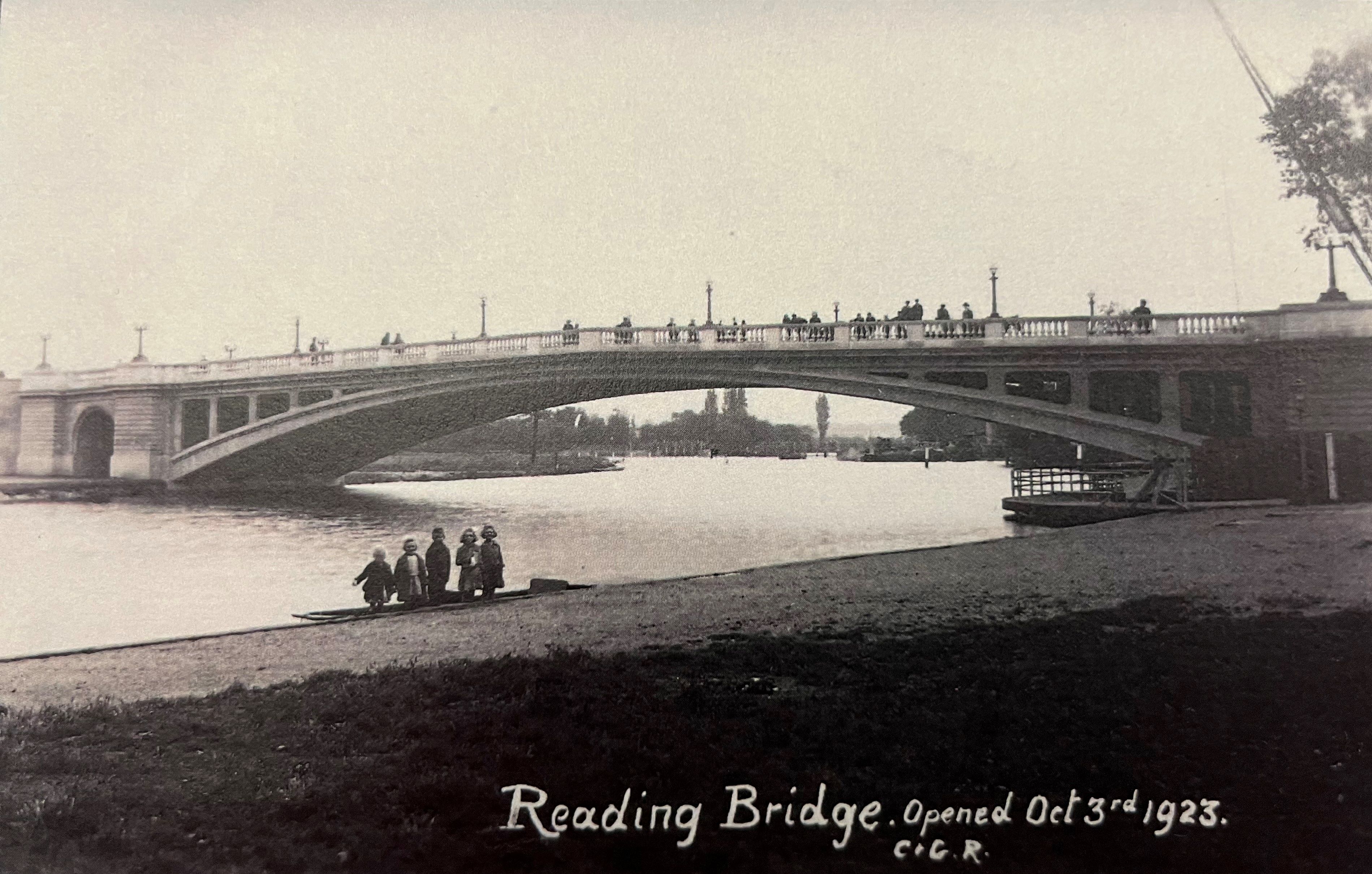

Old postcard showing the bridge after it opened. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

Before the Bridge

Crossing the river at Lower Caversham was not straightforward. There are several references to ferries. A pound lock dating back to 1778 was replaced in 1875. In 1871, the Corporation of Reading had obtained leave to build a swing bridge, just above the lock, but it never came to fruition. The weir was built in 1884.

The Clappers, a narrow plank footbridge that ran past the winding gear of the old weir, was a direct route to work at the Huntley & Palmers factory and the railway. About half of Caversham’s population worked in Reading. As terraced housing grew in Lower Caversham, the Clappers became increasingly busy: a census in 1905 recorded 4836 pedestrians, 19 trucks, 130 bicycles and 70 prams in one day.

Old postcard showing the Clappers and the Weir. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

With rapid growth in new housing on the Caversham side, better river crossings were required; the iron Caversham Bridge was proving inadequate, and the Clappers route was prone to flooding.

Map showing the route for the new bridge included in plans submitted for the parliamentary session 1913. RBA R/acc643.1.

Plans Emerge

The Extension Order required the Corporation of Reading to either replace or widen Caversham Bridge and ‘construct ... a footbridge not less than ten feet in width across the River Thames between the Parish of Caversham and De Bohun Road in the Borough’. With increasing demand and the need to maintain vehicle crossing while Caversham Bridge was replaced, it became clear a second bridge was needed; Charles Powell of Eastfield Caversham offered to contribute £5,000.

In 1913, the Council received parliamentary powers to enable them to erect a vehicular bridge 40 feet wide instead of the footbridge, including new approach roads. A single span of 180 feet would be required with limits of headway and rise. The Thames Conservancy feared that the bridge might slow the flow of the river and it was agreed that the weir should be enlarged, and land cut away, including part of View Island.

A single span and low rise could be achieved by a stiffened steel suspension structure and two designs had already been submitted.

Details of plans submitted by Mr John Webster April 1912. RBA R/acc4447.55.

On 18 Nov 1913 the Borough Extension Committee met, chaired by Alderman John Wessley Martin. In December, Mouchel & Partners, specialists in reinforced concrete, submitted their first report with design and cost for both bridges and work began to acquire land for the approach roads. The outbreak of World War I on 28 July 1914, then halted further progress for almost seven years.

New Methods and Designs

The French inventor and engineer François Hennebique (1842-1921) had developed a means of strengthening concrete using iron and steel bars which provided high tensile strength. Louis Gustave Mouchel, another Frenchman, became Hennebique’s agent in Britain. He made it his life’s work to introduce ‘ferroconcrete’ across Britain and before his death in 1908, founded L. G. Mouchel & Partners Ltd.

The new Reading Bridge would be:

- An elegant modern structure with graceful lines

- Made of concrete, reinforced by steel bars

- 600 feet long with a span over the river of 180 feet

- The largest structure in ferroconcrete in the UK and the longest single span

From journal ENGINEERING 28 September 1923. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

Would this long single span be safe? Mouchel assumed a load of as many traction engines of 20 tons each as the roadway would carry.

The benefits of ‘ferroconcrete’

Although the designs in steel may have saved almost £7,000, it was agreed to proceed with the Mouchel plans. Ferroconcrete needs very little maintenance whereas steel needs protection from the elements. A steel structure gives its maximum strength when new and then deteriorates through corrosion. But a reinforced concrete structure increases in strength after its construction, especially when such masses of concrete are involved.

From journal ENGINEERING 28 September 1923. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

Building the Bridge

Early in 1922, a contract for the construction was agreed with Holloway Brothers Limited of Westminster. Work started in March 1922 and took 18 months to complete.

Four piers were built in the river and a structure across it called ‘falsework’. This supported the shuttering for casting the ribs. The steel reinforcement was then assembled within the shuttering, and freshly mixed concrete placed and compacted in situ. The structure is monolithic, which means that there are no joints in the concrete. Apart from the Portland stone parapets and the northern embankment, the whole structure was built in reinforced concrete.

The main span during construction, showing the piers supporting the shuttering. From a booklet commissioned by the Borough Extension Committee to mark the opening. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

The deck is 40ft (12.2m) wide between the parapets with a road width of 27ft (8.2m) and two footways 6.5ft (2m) wide.

View from the South bank during construction. From a booklet commissioned by the Borough Extension Committee to mark the opening. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

On each side of the river, behind the abutments, is an arch over the riverside footpaths. On the south side is a walkway, above the river, to allow horses to tow barges beneath the main span without interruption. On the northwest and southeast sides of the bridge are stairs to take pedestrians from the riverside paths up to the bridge deck. The Reading approach consists of an arched viaduct connecting to Vastern Road and the Caversham approach is over an earth embankment connecting to the original part of George Street.

Old postcard showing the bridge after the opening. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

Unemployment was very high after the war, and grants from the Unemployed Grants Committee, set up in 1920, helped pay 60% of local wages for building the new road. The total cost of the bridge and its approach roads was almost £70,000, of which £6,000 was donated by Charles Powell of Eastfield Caversham who added investment proceeds to his original offer.

The Lights

After considering designs and costs for lampstands in stone, cast iron or bronze, it was agreed to fix eight large and eight small standard lamps in bronze. Gas filled lamps would be more economical and the globes were to have horizontal bronze bands and bronze caps. Cables and fittings would be provided by the Reading Electricity Supply Co. The total cost was £1,145.

The globes were replaced in the 1960s and again in 2022 when converted to LED.

Drawing by Martin Andrews showing the original lamps.

Around the Bridge

North and south of the Thames, land had to be purchased and cleared to build the approach roads to the bridge.

On the Reading side, De Bohun Road led to the river from Vastern and Kings Meadow Roads. The MacDuff Temperance Hotel was purchased by the Corporation before the outbreak of war and then used for billeting soldiers. East’s Boat Building Company Limited, immediately next to the bridge, received a settlement for lost business.

On the Caversham side, George Street only extended just past the end of the Reading and Caversham Laundry Co Ltd; beyond it were grazing meadows previously owned by Arthur Hill. The road had to be raised and the laundry entrance moved to connect with the new road across the embankment to the bridge.

Access to the river and a new promenade was by stairs down from the bridge deck on both sides of the river, and pedestrian arches under the bridge approaches. As early as July 1923 a quote was submitted for installing a paddling and yachting pool in Christchurch Meadows at a cost of £2,718. The pool opened in 1924. In 1936, the now iconic avenue of 24 Lombardy poplars was planted along George Street to commemorate the coronation of King George VI.

This aerial photograph shows, on the Reading bank, the Men’s Swimming baths built in 1879 and the Ladies Baths – now Thames Lido. On the Caversham bank is the paddling and yachting pool opened in 1924. (1928 C Historic Environment Scotland)

Safety Testing

The testing of the bridge was scheduled for 25 September 1923. Thirty traction engines and Foden wagons , in three rows of ten engines each, lined up and completely covered the bridge. Their combined weight was almost 372 tons, well in excess of the standard rolling load laid down by the Ministry of Transport at 293 tons. The consultant engineers, Mouchel, reported that “the test demonstrated the great strength of the bridge and can be considered as eminently satisfactory.”

Testing the strength of the bridge, 25 September 1923. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

The Opening Ceremony

According to the Reading Standard at the time, the formal opening on Wednesday 3 October was preceded by a luncheon at the Town Hall with speeches. Moving to the bridge, mackintoshes and umbrellas were in evidence, but despite the weather there was a good crowd. At the southern end of the bridge, Alderman Martin, Chair of the Borough Extension Committee, unlocked a chain with a golden key presented by the contractors, Holloway Brothers, and declared the bridge open. The Mayor’s chaplain gave a blessing, and the Mayoral party crossed the bridge. The tablet on the Eastern parapet was unveiled by Charles Powell who had donated £6,000 towards the cost. The tablet on the Western parapet was unveiled by Alderman Parfitt, Vice-Chair of the Borough Extension Committee.

In the evening a supper was given for the employees of Holloway Brothers who had worked on the bridge.

Old postcard showing the bridge after the opening. Courtesy of Reading Libraries.

The Caversham and District Residents Association (CADRA) published a booklet to mark the centenary of Reading Bridge. This is available to buy at Fourbears Books https://www.fourbearsbooks.co.uk/ and is free to download at https://www.cadra.org.uk/readingbridge100