Written by Dr Laura Cleaver, Senior Lecturer in Manuscript Studies, Institute of English Studies, University of London.

Harley 978 contains the earliest known copies of two major works by a writer who calls herself Marie de France (or Marie of France). The presence of these works alone makes Harley 978 extremely important, since Marie was not only an exceptionally talented writer; she was also the earliest known female poet writing in French!

Marie was celebrated as a great poet and entertainer, as even her rival, Denis Piramus, acknowledged. Denis called her ‘Dame Marie’ and noted that she was highly regarded and rewarded by counts, barons, knights and their ladies, although he sourly pointed out that her works are not true stories.

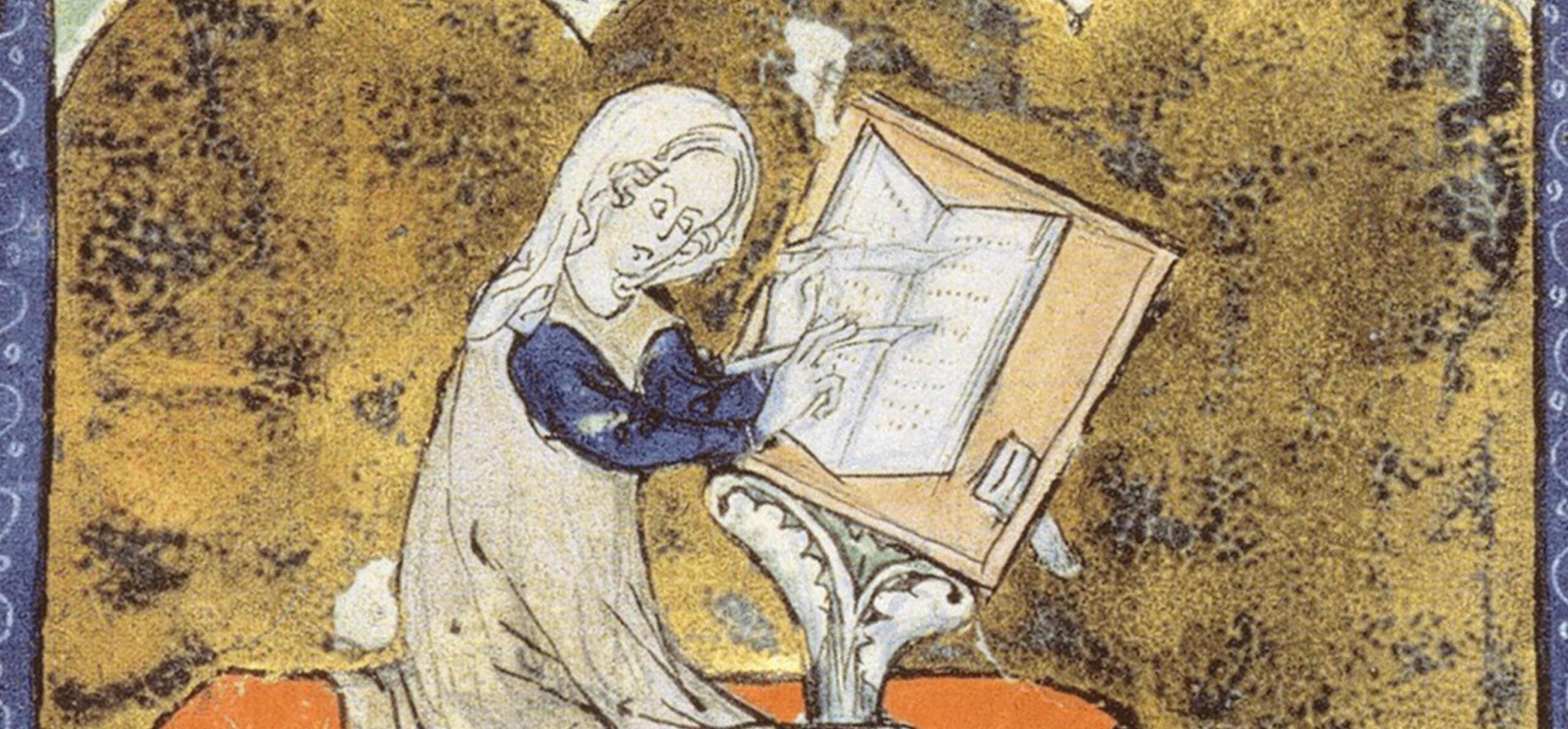

Marie de France: detail from Paris, Bib de l’Arsenal MS 3142, folio 246 (image, public domain)

Marie probably originally wrote both of these works in the second half of the twelfth century. The small number of surviving copies of these texts underlines the important role of monasteries in preserving books in the Middle Ages. Although these works may seem unusual reading matter for the monks of Reading Abbey, such stories were hugely popular, and around the time that Harley 978 was made, scenes from the tales of the knights of King Arthur even decorated a set of floor tiles found at Chertsey Abbey.

This floor tile from Chertsey Abbey, made in the 13th century, shows the figure of Richard the Lionheart. (British Museum: 1885,1113.9051-9060)

Fables of Marie de France

The first text is a collection of fables, starting on folio 40r. Fables are entertaining stories with a moral often featuring animals as the main characters, in the tradition made famous by Aesop. Latin versions of these fables were often used as school textbooks to make Latin translation more entertaining. By providing versions in fashionable French poetry, Marie made these well-loved stories attractive to aristocratic adults!

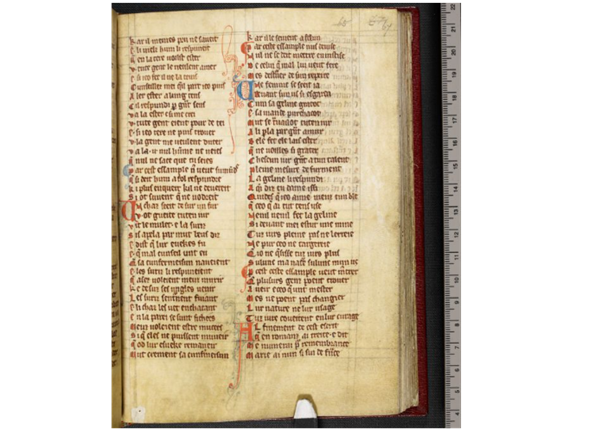

Folio 67 shows the name of Marie de France as author:

On the final line of this page, at the end of the Fables, Marie tells us: ‘Marie ai nun si sui de F[ra]nce’ ('Marie is my name and I am of France'). In the twelfth century, France meant the area around Paris that we would now call the Île-de-France, and large parts of modern-day France were ruled by the kings of England. Marie appears to have worked for members of the English court, and her stories are set in Normandy and Brittany, regions governed by the kings of England. Over the page, she addresses a ‘Count William’, who she flatters as the most valiant count in the kingdom, and for whom she claims to have translated the Fables from English into rhyming French. Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, French was the dominant language of the English ruling elite. In the epilogue to the Fables, Marie places herself in a long line of translators, pointing out that Aesop’s Fables were translated from Greek into Latin, and that King Alfred had then had them translated into English.

The Lais of Marie de France

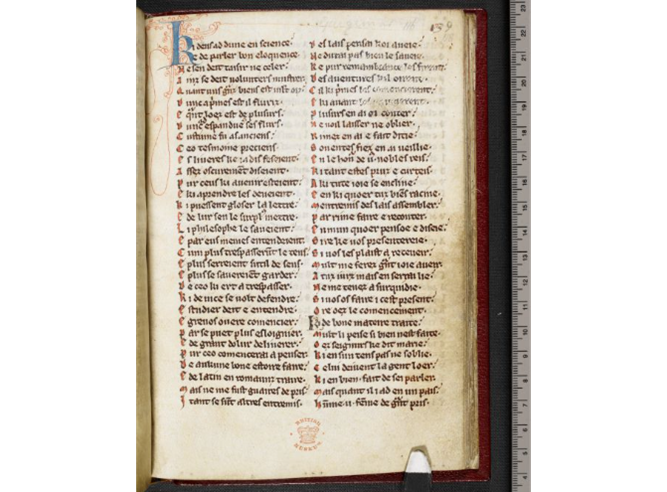

The second text by Marie is a set of stories of chivalry and romance, known as the Lais, starting on folio 118r. These too are in French. Here is its beginning below!

In the prologue to the Lais, Marie declares that she has undertaken to translate these stories from Latin into French ‘in your honour noble king’. She does not specify which king she is addressing, but it is likely to have been Henry II of England, or his son, known as Henry the Young King. Tales of knights and romance were very popular among the extended royal family.

Books presented to royalty were usually more highly decorated than Harley 978, and another copy of Marie’s work, now in Paris, preserves a hint of this. It contains images of Marie writing and holding up her books, all on expensive gold backgrounds (see image at the top).

Marie de France was unusual, though not unique, in being a highly educated woman in the late twelfth century. All that we know about her comes from her writings. Although many theories have been put forward about her identity, she remains rather mysterious. She was probably from an elite family, giving her access to both education and court patronage.

Women play a central and active part in most of the Lais, although, unlike the knights, very few of them are given names. In one of the stories (Chaitivel, f. 149) a woman unable to choose between four knights competing for her love sees three of them killed and the fourth wounded. She arranges burial for the three and treatment for the survivor, before setting herself the task of telling the story. At the end, Marie puts distance between herself and the story’s central character, by declaring that she has just retold a story she had heard, but the idea of women as composers of stories resonates with her own work.

In addition to being authors, women were patrons for works like Marie’s Lais. Chrétien de Troyes dedicated his poem, Lancelot, to Marie of Champagne, daughter of Henry II’s wife Eleanor of Aquitaine by her first husband, King Louis VII of France. Elite women also commissioned other kinds of texts. Henry I’s widow Adeliza (who was a patron of Reading Abbey and was buried in the church) was responsible for a history of the deeds of her husband. This work does not survive, but it may have been related to a volume of the ‘deeds of King Henry and history of Reading’ recorded in a list of books at Reading Abbey in the Middle Ages.