Blog written with the invaluable guidance of the Royal Berkshire Medical Museum.

Across the UK, people are acknowledging the vital work of the NHS and key workers in responding to the coronavirus pandemic.

One of the temporary hospitals built in London, NHS Nightingale, celebrates the life of one of the most pioneering nurses in our history: Florence Nightingale. Nightingale gained national attention for her nursing during the Crimean War. After returning to the UK in 1856, she used her new-found fame to transform nursing into a highly respected profession.

On Nightingale's 200th birthday, we’re looking back at her impact on the Royal Berkshire Hospital here in Reading and what the Hospital’s life was like in the 19th century.

27 May 1839 - The Royal Berkshire Hospital Opens

The Royal Berkshire Hospital began its life as an independent charitable organisation. The former Prime Minister, Lord Sidmouth, donated the site, and the hospital was built by public subscription. Sidmouth’s initiative was supported by King William IV (1765 – 1837), who granted the use of ‘Royal’ in its name.

By the end of July 1839, the Royal Berks had admitted fifty-nine inpatients: forty-nine men and ten women. There were thirteen medical cases and forty-six surgeries; ten of these resulted from railway accidents during the construction of the Great Western Railway cutting at Sonning. Three operations were all unfortunately amputations due to rail-related accidents.

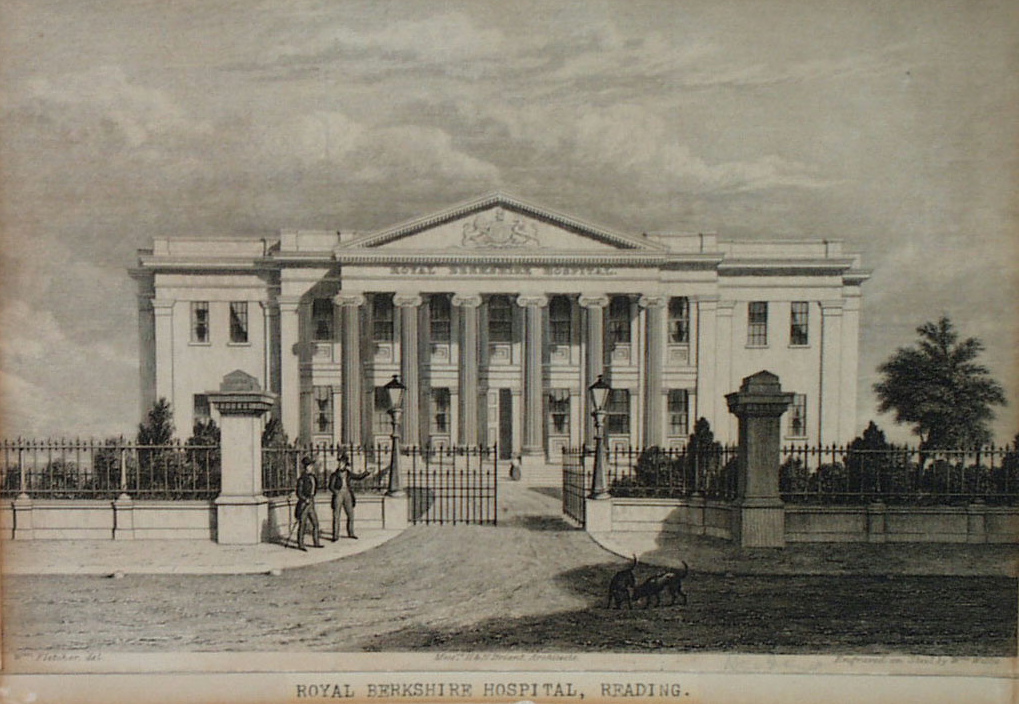

Engraving of Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading. Drawn by William Fletcher, and engraved by William Willis, 1830s (museum object no. 1931.127.1)

The first 'nurses'

The Royal Berkshire Hospital’s first matron was Mrs Sophia Hogg, who had previously worked at St George’s Hospital, London. As matron, Hogg was responsible for an enormous range of duties across the hospital, including ordering goods and furniture, managing inventories, overseeing diet sheets, handling patient’s effects, organising provisions, and supervising both nurses and servants. Hogg received a salary of £30 a year in addition to board and lodging, and served until 1846, when she resigned due to ill-health.

At this time, the hospital had two wards – one for men (Benyon Ward) and one for women (Victoria Ward). Both were sparse, with high ceilings, bare wooden floors and iron bedsteads. There was one coal fire for heating, one closet for washing, and one bathroom per ward.

Matron Hogg was supported by two nurses. A man, Alfred Cotton, looked after the men, while a woman, Nurse Hollis, cared for the women. Each received a salary of £12 a year. In comparison, the cook was paid £15, the housemaid £8, and the porter £20. This included board and lodging, but all had to supply their own tea and sugar!

As more patients were admitted, the Hospital opened two more wards – Sidmouth (men’s) and Adelaide (women’s) – and hired two further nurses: Nurse Maskell and Nurse Page.

At this time, the duties of a nurse were very different to today. Nurses cleaned wards, served meals and kept an eye on patients, but they had no qualifications. Their only medical duty was to see that patients took the medication that was prescribed by the medical staff. Most nursing applicants came from workhouses and were often rather unfortunate characters, dealing with social and medical issues of their own.

Victoria Ward, one of the Hospital's original wards in the early 20th century (Royal Berkshire Medical Museum)

Unsuitable nurses and complaints

It wasn’t long before Matron Hogg declared that Alfred Cotton, the Hospital's only male nurse, was inefficient and ‘not a proper person for the appointment’. She had received a report from the House Surgeon that Cotton was negligent in his duty and had fallen asleep when in charge of patient on the eye ward! Hogg dismissed him, and sought to replace him with a woman, as she believed that a woman would provide more satisfactory care.

Nurse Hollis and Nurse Maskell formed a solid core, but finding more nurses to work alongside them represented a significant challenge, and the Hospital’s part-time staff was a revolving door.

Cotton’s replacement, Nurse Butler, could neither read nor write, and so the House Surgeon was required to check that the right medicines were being given to the right patients. Nurse Isabella Jones was literate, only to be dismissed after being found drunk, having stolen spirits from the dispensary. Another nurse seemed a good fit, until she was identified as having been a barmaid at a local pub, an association that, for the Victorians, didn't sit right at all.

By the 1850s, the Hospital admitted double the number of patients but still had only five nurses and one night-nurse. Female patients regularly complained of ill-treatment and cruelty, and the Board received many anonymous letters. The chief allegation was that patients were being made to scrub the wards when they weren’t well enough to do so. Nurses were responsible for cleaning the wards and were allowed to call on the help of able-bodied patients. In 1853, the Board agreed to hire dedicated cleaning staff, and complaints subsided.

Advice from Miss Nightingale

Upon her return to England in 1856, Florence Nightingale promoted the importance of good nursing and hygiene in hospitals. However, her innovative solutions would take a while to be embraced by the Royal Berks!

Initially, improvements were held back by the difficult character of the incumbent Matron – Matron Tillbrooke – who served from 1850 until 1860, leaving just as the hospital expanded with two new wards. These were described as airy and pleasant, and increased the Hospital’s capacity to one hundred beds.

In 1863, the Hospital was inspected on behalf of the Health Department of the Privy Council. While the inspectors were ‘much pleased by the building and the general arrangements’, they noted that the staff was insufficient in comparison to similar institutions. In the years that followed, the Hospital Board reviewed its service, and by 1866 was considering fundamental changes, which included hiring trained nurses for the very first time.

Florence Nightingale’s nursing institution, and others, were approached for advice, and the Hospital Board received several ‘kind and invaluable’ letters from Miss Nightingale herself! This culminated in June 1866 when the Board entered an agreement with a Dr Falconer of the Bath Home for Trained Nurses. The Home would supply the Royal Berks with one trained Superintendent Nurse and three trained nurses. In exchange, the Hospital would give training to the Home’s probationers.

In August, 1866, the three trained nurses and the new Superintendent herself – Miss Smith – arrived. Within a week, Smith asked for three more nurses, increasing nursing staff to ten, alongside further kitchen and laundry staff.

‘A visible improvement in the general management of the wards’ was noted, but the agreement was short-lived: by December it was terminated completely, and recruitment and nursing management returned to the control of the Hospital.

Nevertheless, the Hospital ended the 1860s in a considerably improved position. The Board noted that nursing staff were ‘greatly superior in education and intelligence to those previously employed’, and nurses received a well-earned pay-rise. They were also given materials to make their own clothing (although their creations remained the property of the hospital)!

Mary Seacole - nursing pioneer

Another medical pioneer of the Crimea was Mary Seacole, a ‘doctress’ who practised Creole or Afro-Caribbean medicine and had learnt nursing and herbalism from her mother. Mary heard about the Crimean campaign and travelled there where she set up her own business, the British Hotel, a general store and a place where soldiers could come to be nursed. She was affectionately known by the troops as Mother Seacole, because of the care she gave them. In Reading she is commemorated by the Mary Seacole Nursery and she also features on Reading's 1990 Black History Mural (her image is held by Reading nurse Shirley Graham-Paul who worked to raise awareness of Seacole's legacy). There has been a call to name one of the new temporary Covid-19 hospitals after her, to honour her contribution to the development of nursing.

Late 19th century developments

In June 1871, a new Superintendent arrived at the Hospital, on a salary of £70 a year: Miss Ann Baster.

Baster’s tenure at the hospital oversaw many significant changes. Under her guidance, the Hospital added a new nurses’ home on the east side of the site, facing London Road, and a new outpatients and private nursing department on the west. The outpatient department was reorganised, and a private nursing scheme was introduced. By the time of completion in 1873, the hospital featured ten main wards, two convalescence day wards, and seven small side rooms.

Matron Baster suggested that the Hospital should have its own ward specifically for children, which was opened in 1874: ‘Alice Ward’. It was described as more like a nursery, with toys, games and a cheerful atmosphere.

In the twenty-years that followed, the Hospital staff expanded considerably. An Assistant Matron, seven additional ward sisters and six private nurses were all appointed. This included the first male nurse since Alfred Cotton’s dismissal in 1839 for sleeping on the job. The male nurse’s duties included attending the post-mortem room, cleaning surgical instruments, and bathing male patients (and later massage).

In May 1895, the House Committee received a complaint made against a nurse. It was found to be justified and the nurse was dismissed. Unfortunately, the House Surgeon who had made the complaint had not notified Miss Baster. She queried how she could be responsible when she had not been informed, but the House Committee accepted charges of inefficient nursing and recommended that reorganisation should take place.

It was stated that any new matron should be aged between thirty and forty years and have full professional training and knowledge of hospital administration. For this, she would receive a salary of £100 a year.

All of this resulted in Matron Baster’s resignation at the age of sixty-three. While the Hospital board expressed their great appreciation for her twenty-four years at the helm, in which important and worthwhile work was achieved, the tone used by the medical staff was contrasting: ‘no formal notice was to be taken of Miss Baster leaving’, they said.

Miss Baster (seated) Royal Berkshire Hospital Matron, with other staff about 1892 (Royal Berkshire Medical Museum)

1899 - financial crisis

As the 19th century drew to a close, the Hospital board was presented with a far-reaching report into the Hospital’s financial position and administration. The report found that patients at the Royal Berks stayed for far longer than at similar institutions, an average stay of forty days compared to twenty-eight days elsewhere. This was adding considerably to the hospital’s annual deficit of £1,500 per annum.

To remedy this, efficiencies were made, including ward closure and reducing the number of nurses to twenty-seven. This did ultimately reduce the length of the average stay, and left the Hospital on a firmer footing to start the 20th century.

The Royal Berkshire Medical Museum

You can discover more about health and medicine in Berkshire's history at the Royal Berkshire Medical Museum located in the hospital's old laundry building. See their website for opening hours and other events.

Further Reading

Margaret Railton and Marsall Barr, 1989, The Royal Berkshire Hospital 1839-1989, The Royal Berkshire Hospital

Look out for our next guest blog, coming later this week, by Richard Havelock, Chairman of Berkshire Medical Heritage Centre: 'From Sarah Gamp to Emergency Ward 10: Florence Nightingale and the birth of the nursing profession'.