This blog marks UK Disability History Month (16 November – 16 December). Join us as we explore objects in our collection that shed a light on aspects of disability history, and society’s changing attitudes towards disabled people. We also look at how Reading Museum's galleries and services have been made accessible over the last 100 years.

One of our welcome volunteers talking to a museum visitor

Reading Abbey: caring for the sick and infirm in medieval Reading

From the 12th century until its dissolution, Reading Abbey provided care and support to the poorest and most vulnerable in the medieval town through its almshouses, guest houses, and hospitals. This included a leper hospital built by Abbot Anscher, the second Abbot of Reading, between 1131 and 1135.

The abbey's leper hospital was located on the eastern boundary of Reading in what is known today as Cemetery Junction (after the later 19th century Reading Cemetery). One of the female skeletons found at the site, and now in our collection, shows evidence of a rudimentary medical treatment: copper plates around one arm, thought to hold an ivy leaf dressing, possibly a treatment for ulcerated skin caused by leprosy or another skin disease.

A medieval man with leprosy from one of Abbey Quarter interpretation panels that explore Reading Abbey's history

William More, Tudor harpist and composer

In 1971, Reading Museum published a book titled Reading Abbey - An introduction to the music at the abbey by Peter Marr. This includes an account of William More, a blind harpist and composer from Reading, who in 1520 was described as the principal English harpist. More travelled across England to play for the rich and powerful. It was said he succeeded in rising from a beggar to gentleman. More was born in about 1490 and was first mentioned in the churchwarden accounts of St Laurence’s Church in 1507-08 when he was paid four pence to play at the church’s May-tide festivities.

By the 1530s, More was employed by both King Henry VIII and his chief adviser Thomas Cromwell. He was paid five pounds for playing at the royal household’s New Year celebrations in 1538-9, only months before Henry dissolved Reading Abbey on 19 September 1539.

It was at this time that More became caught up in the tensions between Henry VIII and Cromwell, and the Abbot of Reading Hugh Faringdon. More was accused of acting as a messenger between Hugh Faringdon and Richard Whiting, Abbot of Glastonbury. Henry VIII later executed both abbots for treason. More was imprisoned by Henry VIII in November 1539 but was released in time to play at the royal household’s New Year festivities of 1539-40. His musical career continued under Queen Elizabeth I until he died in 1565.

hadst thou nought to do but to become a traitorous messenger between abbatt [abbot] and abbatt?…Nay verily, thou shalt be called William Moor the blind traitor…thou wast blind in your eyes and they were blind in their consciences.

- Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, 1539, no 613

Medieval monks playing an organ

William Moon, inventor of Moon type

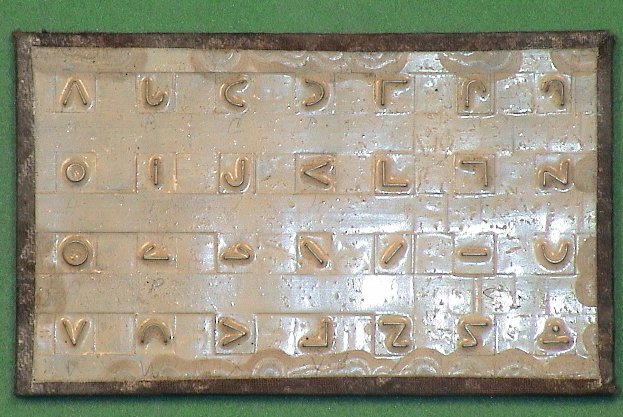

The museum’s collection contains a 19th century alphabet board for teaching a written language for blind people called Moon type. This was developed by Dr William Moon of Brighton in 1845.

As a child, Moon suffered from scarlet fever, which severely damaged his eyesight. His sight then deteriorated until he became totally blind at the age of 21. Having lost his sight, he decided to teach other blind people to read, using the embossed systems currently available. However, he discovered that many of his pupils found it extremely difficult to use these systems and so decided to create a new, easier option. By using his Moon system he was able to teach a blind boy, who had been struggling with the other embossed systems for five years, to read in ten days.

Many of the symbols used in Moon type are simplified forms of letters from the standard Roman alphabet (the alphabet used by sighted people to write English). This may be why those who lose their sight later in life find the Moon system easier to learn than other systems, like Braille, as they are able to recognise the symbols. The type is read using the fingers to feel the shapes of the symbols.

This Moon board has 28 characters embossed onto the surface. These symbols represent the 26 letters of the alphabet, and the words ‘and’ and ‘the’. The board would have been used as an aid to help learners familiarise themselves with the characters. The symbols can also be used to represent sounds, words, parts of words and numbers.

Moon Board. Top row: A-G, second row: H-N, third row: O-U, bottom row: V-Z; 'and' 'the' (Museum object no 1933.113.1)

Private Edward Beesley: successful graft surgery

Edward Beesley was born in Reading in 1897. Beesley joined the Royal Berkshire Regiment in 1915 as a private and saw active service in the First World War. He was wounded at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, losing his right thumb. In October 1916, he was honourably discharged from the army due to this disability, one of more than two million British soldiers wounded during the war.

On his return to Reading, Beesley was admitted to the Royal Berkshire Hospital, which had opened dedicated military wards in response to the high number of war casualties. Here, he underwent an experimental procedure, conducted by Dr J. L. Joyce, to graft the third finger of his left hand onto his right hand to create a replacement thumb. To ensure the graft was successful, it was necessary for Beesley to have his hands clasped together for several months.

Whilst recovering from the graft, Edward Beesley embroidered a badge of the Royal Berkshire Regiment. The act of sewing the picture would have stimulated the muscles in his hands, and trained his new thumb. Following the success of the graft, Edward Beesley is reputed to have shaken hands with Queen Mary.

The photo below shows Edward Beesley on his wedding day in 1921 with his bride, Miss Rebe Case. The result of the graft can be clearly seen.

Edward Beesley and Rebe Case on their wedding day in 1921, the result of the graft can be clearly seen (Museum object no, 1997.133.1)

Object handling at Reading Museum

Our records show that Reading Museum began loaning objects for handling to Reading schools in 1911. Over the years, the loan service grew to around 2000 collections of artefacts and pictures, covering the whole of the school curriculum and reaching all schools, care homes, day centres and hospitals across Reading.

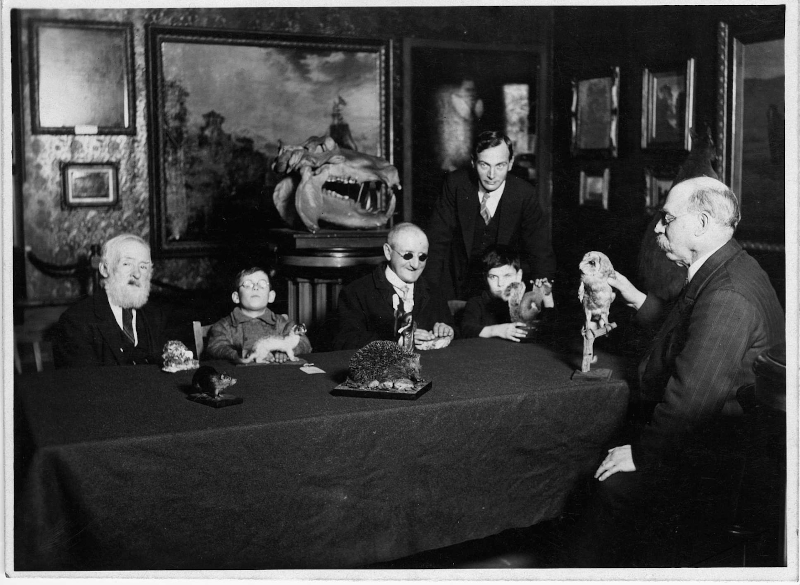

In the 1920s, the museum’s first professional curator William Smallcombe introduced collection handling sessions for local blind people. Smallcombe was an innovator in museum education. He had become interested in the welfare of blind people while he was the deputy curator at Sunderland Museum, where the chief curator Mr Charlton had started 'the movement for showing museums to the blind'. At Reading, Smallcombe devised 'lessons' in which groups of blind people could handle taxidermy and other objects. Most of the specimens used in the session in this photograph are still recognisable in the collection, including the hedgehogs and barn owl. We continue to run handling sessions for visitors to the museum and out in the local community.

Blind visitors handling natural history objects at Reading Museum, 1 July 1930 (Museum object no. 2007.1302.1)

Changing attitudes to disability

Charity boxes were a common sight on Britain's high streets in the 1960s and 1970s. They were placed outside shops to attract the spare change of passing shoppers. The museum has an example of a Spastics Society charity collecting box from the 1960s. As attitudes towards disability changed, the image they presented of disabled people became outdated and caused offence and they were withdrawn from use.

Charity collection boxes made of moulded plastic were often shaped to represent people and animals to catch people’s attention. This box depicts an image of childhood, a young girl holding a teddy bear, but closer inspection of the model shows us why they were withdrawn. The girl depicted has cerebral palsy, a muscle tone disorder. She is wearing callipers; leg braces designed to aid a person’s ability to move. She also holds a tin that asks, 'Please help your local spastics'. People with cerebral palsy did not want to be presented as helpless and in need of pity; they wanted acceptance and an equal place in society.

The Spastics Society was formed in 1952 by a group of parents whose children had cerebral palsy. The Society aimed to improve the services available to people with this disability. However, the true meaning of the word spastic became overshadowed by slang. It came to be used as a playground taunt, and as an abusive term for anyone with a disability. In 1994 The Spastics Society changed its name to Scope and now campaigns for disability equality.

Spastics Society charity collecting box, 1960s (Museum object number 1997.72.17)

Access for all

In October 2022, we were delighted to learn that this website was among the UK’s top 20 for its online access information. The Heritage Access 2022 report, led by VocalEyes and supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, reviewed the online access information of 3,150 museums and heritage sites. The access information for both Reading Museum and the Riverside Museum at Blake’s Lock was independently reviewed by volunteers from a team of 61 researchers (many with lived experience of access barriers).

However, we are not resting on our laurels and we continue to regularly review and update our access provision, including online information, in line with our Access Policy. We firmly believe that people are disabled by the barriers of attitude, environment, and organisation in society, not by their impairment or medical condition. We continue to remove barriers identified by our access audits, visitor, staff and volunteer feedback, and engagement with local support and advocacy groups.

Workshops and tours

Reading Museum has an ongoing relationship with Berkshire Vision, a charity providing support and activities for visually impaired children, adults and their families. In the last few years, we have developed and delivered tactile workshops for children and young people and audio-descriptive tours of Britain's Bayeux Tapestry for adults. The tactile workshops give visually impaired young people the opportunity to handle a variety of museum objects, from ancient Greek pots and Egyptian shabtis to modern sculptures. Inspired by the experience of shapes and textures they create their own art using modelling clay. It is an immersive and interactive workshop which gives visually impaired young people an exciting opportunity to express their creativity through art.

The young people were very engaged in handling the objects and making something in clay…. we were late finishing as they were so keen! Thanks very much for being so flexible and accommodating to the group.

- Berkshire Vision team

Our audio-descriptive tour of the Bayeux Tapestry for visually impaired adults are supported by using paddles with 3D relief drawings of scenes of the tapestry. These add a tactile experience of the artefact to its verbal description by the audio guide.

It was a great experience, and the ramp and lift helped a lot.

- Berkshire Vision team

Children visiting Reading's Bayeux Tapestry

School visits

Reading Museum’s work with disabled children is embedded in all our standard learning activities. Before a school group visits the museum for a session, we take the time to meet the teachers and learn about their pupils’ special needs. We want to be prepared to support all children in the best way possible on the day of their visit so that all of them can get the most out of their experience. For example, we have breakout rooms equipped with beanbags and sensory bags for those children who sometimes need to have a quiet moment away from the rest of the group.

We know that special needs schools have often found barriers to using our education offers as they have very small groups of children with very different disabilities for whom a one-size-fits-all offer doesn’t work. So where possible we try to organise sessions tailored to the needs of a group or even a single child.

This summer, we worked with year nine students from Addington School, a local special needs school, and old Reading Cemetery to engage pupils in the environment and history of Reading. The project had several strands, involving our learning team visiting the children in the school, and the children visiting the museum as well as the cemetery. As part of the project, they completed artworks and showcased these to the museum team at the end of the project. The children gained experience of the museum environment, and our team really enjoyed sharing information and exploring their achievements.

Museums, My Way

Finally, with The Museum of English Rural Life (our partner in Museums Partnership Reading, a collaborative programme of activities supported by Arts Council England’s National Portfolio Organisation programme) we developed Museums, My Way, a series of free sessions for neurodiverse visitors of all ages. Developed with Autism Berkshire, these provide a safe environment to explore the museums at times when they are usually closed to the public or are less busy. There are facilitated activities on themes inspired by the museums’ collections, and a quiet break-out space. Siblings, families, carers and friends are all welcome. Find out more on the Museums, My Way page. Museums, My Way is part of Museums Partnership Reading,.

If you are planning to visit us, you'll find everything you need to support your visit on our access page. We look forward to seeing you.