At the end of 2021, a guest article was featured on the Reading Museum blog by John Nixon, author of The Gentlemen Danes. It explored the remarkable story of Reading’s Gentlemen Danes. These were Danish prisoners of war–often sailors–captured by British forces during the Napoleonic Wars. Many Danish officers served their sentences on parole, living freely among the English population (with the one proviso that they were unable to leave the country). One of those parole towns was Reading, and the Gentlemen Danes left a lasting impression on our town.

Of all the Danish prisoners of war, one figure whose story stands out from the rest is a Dane by the name of Jørgen Jørgensen. In various times of his life, Jorgensen was the first Dane to circumnavigate the globe, a privateer and explorer, a socialite, a writer, a spy, a prisoner and a policeman, and (in the unlikeliest turn of them all) the King of Iceland.

In this blog, we explore the story of Jørgensen’s life in England, and the personal and political history of a man described as ‘one of the most interesting human comets recorded in history’. As his trail blazed through the dawn of the 19th century, Jørgensen’s path entwined with Reading’s, and we highlight his known and likely links with the history of our town. Jørgensen’s legacy was a complex one, particularly during his time in Tasmania, and we discuss this and its implications at the end of the article.

From clocks to docks

Jørgen Jørgensen, born on the 29th March 1790, was the son of a Copenhagen clockmaker, who left school at age fifteen with dreams of glory. He enrolled as an apprentice on an English collier (a ship carrying coal), the Janeon. Over thirteen years he became an accomplished sailor, privateer, and whaler, on a journey that took him from Copenhagen as far as Cape Town and Tasmania.

When Jørgensen returned to Copenhagen in 1807, he witnessed his hometown become embroiled in the conflict that was raging across Europe: the Napoleonic Wars. Though Denmark-Norway’s stance was of armed neutrality, Copenhagen was attacked in August 1807 by the British navy. This action had the goal of capturing the Danish fleet, to prevent it from falling into Napoleon’s hands. Britain bombarded Copenhagen with missiles–including around 300 Congreve rockets–until the city surrendered. Over a thousand homes were destroyed in the attacks, and many lost their lives.

Nicholas Pocock: The Battle of Copenhagen, 2 April 1801. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

After the guns fell silent off the Copenhagen coast, and the British navy absorbed the Danish fleet into theirs, the Danish government instigated a naval war against Britain. Jørgensen enlisted in the Danish navy as the captain of a privateer brig, the Admiral Juel (variably known as the Admiral Jawl).

Jørgensen’s commission, with his years of varied maritime experience, quickly paid off. Within months of enlistment, he brought three prizes back to Copenhagen: an English and a Prussian merchant ship, and a Swedish fishing boat.

However, like the many Gentlemen Danes in Reading, Jørgensen’s war didn’t last long. On the 2nd March 1808, the Juel was intercepted off the English coast at Scarborough by a British ship of the line, the HMS Sappho. On approach, Jørgensen’s crew had the audacity to hoist a British flag. These wiles didn’t convince the Sappho’s captain, who correctly perceived that the boat, with ‘the appearance of a man of war’, seemed ‘to have no other for its object than to cut of (sic) several vessels to leeward of her’. The Sappho fired a warning shot. In response, the Juel raised a Danish flag and brazenly replied with cannon fire. This refusal to surrender conjures up the mix of bravery, optimism and naivety that will recur throughout Jørgensen’s life.

After forty-one minutes of engagement, in which the Danes suffered one fatality, the Juel and its crew were captured.

This painting, made by the English painter Francis Sartorius II, shows the moment that the HMS Sappho captured the Admiral Juel. (RMG, BHC0582)

Winning and losing the lottery, and the eruption of Laki

As a member of the officer class, Jørgensen was granted parole by the British and allowed to see out his sentence in comfort, provided that he remained in the country. At this time, he took up lodgings at the Spread-Eagle Inn on Gracechurch Street, London.

Like much of Jørgensen’s life, the highs were followed by lows; and the lows by highs. Soon after arriving in London, Jørgensen won a significant amount of money in the lottery. He supplemented his winnings with a £1,000 loan, and made the decision to invest in cargo and smuggle it into mainland wartime Europe.

True to form, Jørgensen's cargo vanished at sea. It was possible it had been seized by the French, in the same way that Jørgensen himself had been captured by the British. Wherever its final destination, Jørgensen's small fortune vanished with it. Only the debt remained.

However, there was much that Jørgensen liked about his stay in London. It is likely that at this time he also travelled to Reading, where many Danish officers were paroled. We will talk more about how we know this and Jørgensen's life in Reading later on!

A highlight of Jørgensen's time in England was the people that he met and the network of connections that he made. These included many businessmen and traders with remarkable stories to tell. Among them were two Icelandic merchants by the name of Bjarni Sívertsen and Weste Petræus. Sívertsen, Petræus and Jørgensen had all met a similar fate: captured by the British at sea. And though the two Icelanders hadn’t fired cannons at the British, they were considered fair game, due to Iceland being a colony of Denmark-Norway.

From these Icelandic merchants, Jørgensen learned about the stark impact that the war was having on Iceland and its people. Denmark-Norway maintained a commercial monopoly over Iceland, and was its sole provider of critical supplies (often at exorbitant prices). The actions of the British navy, aggressively capturing merchant ships, prevented the delivery of key resources, and Iceland’s situation was quickly growing bleak.

For the people of Iceland, the timing of this couldn’t have been worse. The 1780s had borne witness to an enormous volcanic eruption. Between June 1783 and February 1784, fissures at Laki (within Iceland's Vatnajökull National Park today) erupted to devastating effect, producing (it is estimated) 42 billion tons of lava and clouds of poisonous gasses. The impact had been catastrophic: almost all of the island's crops were destroyed, around 50% of its livestock perished, and from years of famine that ensued, close to 69% of the Icelandic population died.

The central fissure at Laki, also known as Lakagígar (meaning 'the craters of Laki). (Credit: Chmee2/Valtameri, Wikimedia)

In this moment of jeopardy, Jørgensen identified a double opportunity. It was a chance to be a hero, bringing essential supplies to a people in need. At the same time, it bore commercial prospects, and the possibility of recouping some of those lost lottery winnings that now filled Napoleon’s treasury, or loomed at the bottom of the sea.

From prisoner to Protector

Many of the Danish prisoners on parole in England would travel from town to town, and enjoy the best that the English countryside had to offer. However, none broke the terms of their parole so liberally as Jørgen Jørgensen. On the 29th December 1808, at Liverpool harbour, Jørgensen embarked upon a ship named the Clarence and sailed to Iceland. Not once, but twice.

Jørgensen’s Icelandic enterprise was in partnership with two English merchants: James Savignac and Samuel Phelps. The tree had the support of Sir Joseph Banks (the botanist, President of the Royal Society, and later co-founder of Kew Gardens). Banks had been liaising with the two Icelanders that Jørgensen had befriended. He held a lifelong interest in Iceland ever since visiting the island as a younger man. Through his wealth of connections and contacts, he was able to ensure that the Clarence had all the legal papers that it needed to embark upon the journey north.

Jørgensen and Phelps’ first expedition was in some ways successful, yet tempered by disaster. Predictably, the Clarence met a hostile reception from Iceland’s colonial government, who were officially at war with Britain. Particularly after the Battle of Copenhagen, it is easy to see that a ship displaying the Union Jack would not have been a welcome sight.

After bartering that was more akin to bullying (with outright threats), the English merchants forced an agreement to bring the cargo ashore. Unfortunately, though, Jørgensen, Phelps and Banks’ humanitarian aspirations (which were genuine) found a poor choice of destination in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik. The city's population (of around 300 permanent residents) were all largely affiliated with the colonial Danish government, and privileged as a result. These were not the starving rural Icelanders who the supplies were needed to reach. In this sense, the first expeditation was both commercially and humanitarianly a disaster.

It was during the second Icelandic expedition (which, ironically, sought to recoup some of the merchants’ losses from the first) that the situation escalated. The Danish governor of Iceland, Count Trampe, had been absent from the island when the informal trade agreement had been reached. After he returned, he was horrified to hear how the local authorities had capitulated to the traders’ demands. The agreement was immediately scrapped, and when Jørgensen and his allies arrived (this time on a different boat, the Margaret and Ann), they found, to their ire, that there was no deal to be had.

So, with an army of eight (yes, eight) sailors, Jørgensen descended into Reykjavik, captured Trampe, imprisoned him aboard their boat, and installed himself as the ruler of Iceland. It was to be a very unexpected revolution. Iceland had a rich history but little nationalistic sentiment. And whilst eight sailors might sound like a very small number of troops, it was the ship that they arrived on that did all of the convincing. Reykjavik was very much undefended, and the cannons on board the Margaret and Ann were proportionately as threatening as the British fleet that attacked Copenhagen two years earlier.

On the 26th of June 1809, six months after setting sail from Merseyside, Jørgensen proclaimed himself ‘His Excellency, the Protector of Iceland, Commander in Chief by Land and Sea’. Effectively, whilst serving his parole, he had become the King of Iceland.

The notion of a nation he now had to lead

Jørgensen’s vision of Iceland was one of social democracy and liberty, inspired by the revolutionary struggles of America and France. He attempted to restore the ancient Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He sold grain at heavily discounted prices, toppling the exploitative practices and monopolies of the Danish colonists (including the then-imprisoned Count Trampe, who had lucrative trade with the island he governed). And he communicated his plans through a range of proclamations (that quickly grew more regal in tone, bearing shades of Napoleon himself).

However, Jørgensen’s reign was as short-lived as it was surprising. Within less than two months, a military vessel arrived at Reykjavik harbour. It bore not the flag of Denmark-Norway, as you might expect, but of Great Britain. And its crew were not interested in Jørgensen the Protector of Iceland. They were here for Jørgensen the prisoner, who had broken the terms of his parole with as much gusto and drama as quite possibly anyone in the whole of English history.

Jørgensen was taken back to Britain, where he was found guilty of breaking the terms of his parole by the Transport Board and imprisoned for two years. But before he left Iceland, he did accomplish one final act of heroism. As the cannon-clad ship he arrived upon, the Margaret and Ann, began sailing away from Reykjavik harbour, returning to England with all of the purchases that Phelps had made (including highly flammable oil and tallow), the boat burst into flames. Jørgensen sailed out and rescued the ship's crew and passengers, but all the cargo was lost and the ship sank. The merchant Phelps was bankrupt by the time he arrived back home.

Down and out in London and Reading

After the end of his unique Icelandic saga, Jørgensen’s life showed no signs of slowing down. One highlight of the next ten years was to be his brief career as a spy for the English intelligence service, travelling across France and Germany during the latter stages of the Napoleonic Wars. And true to form for a man who seemed to crop up everywhere, like the turn of the nineteenth century’s answer to Forrest Gump, Jørgensen was even at the Battle of Waterloo, which was just a little larger in scale than his eight-man siege of Reykjavik.

Whilst Jørgensen’s spirit of adventure kept up the pace, so did his debts, which resulted in several stays in debtors’ prisons. In fact, it is in the paper trail of his many creditors that we find the evidence of his connections to Reading.

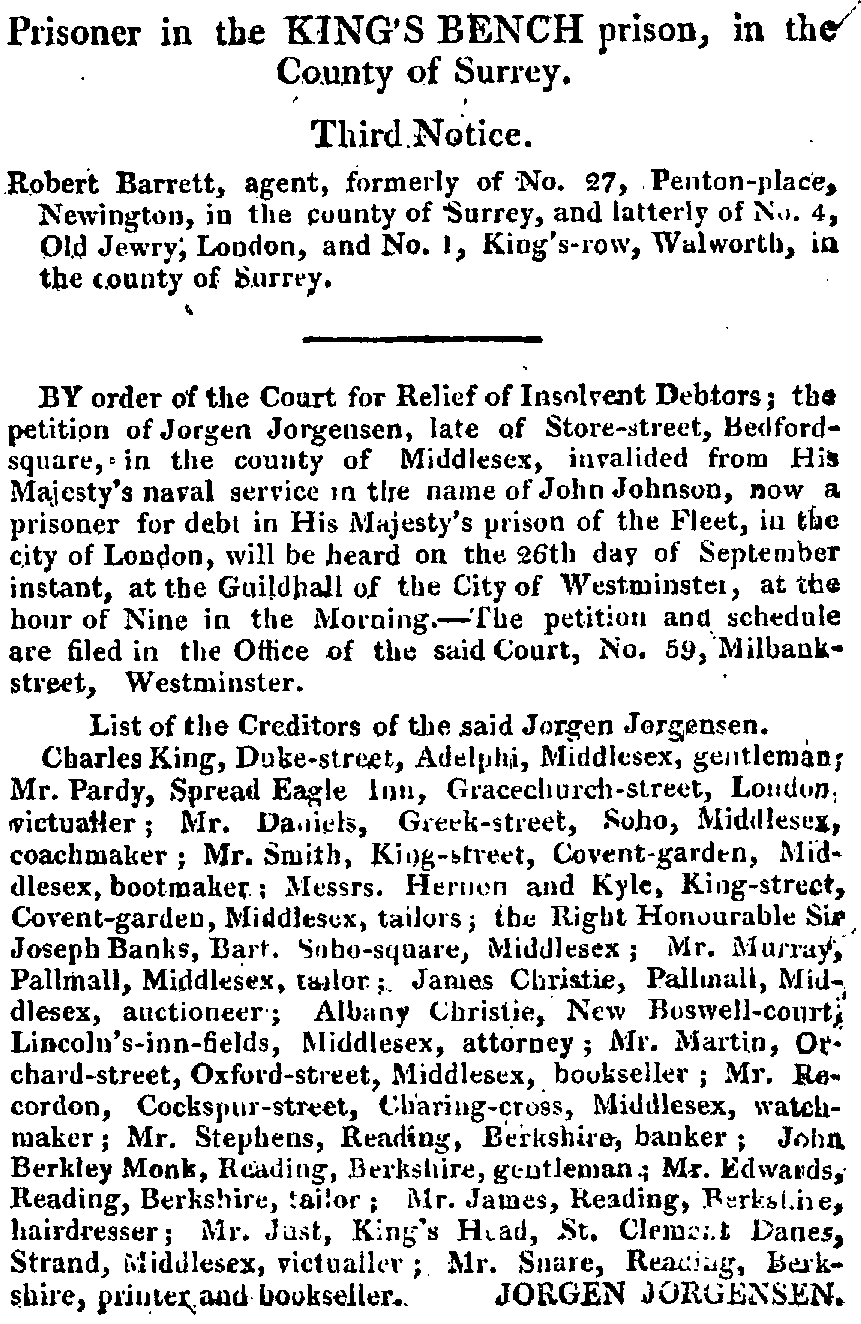

In 1814, a full list of Jørgensen’s creditors was featured in The London Gazette (ahead of an appearance for Jørgensen in court).

The London Gazette, 6 September 1814

Jørgensen's list of creditors includes many recognisable names from early 19th century Reading’s high society. Just as he was fraternising with influential figures like Sir Joseph Banks before his Icelandic forays, it is clear that Jørgensen continued to make connections with notable figures in Reading too (and, equally, owe them substantial amounts of money).

John Berkeley Monck was the son of a wealthy Bath landowner, who moved to Reading in 1796 to practise law. He became a local landowner (living at Coley Park), was involved in local politics, and served as MP for Reading from 1820 until his retirement 1830. Although known as 'the absent-minded member', Monck was a champion of parliamentary reform and supported the abolition of slavery. It is interesting to think whether Monck ever learned about Jørgensen’s own unlikely attempts at parliamentary reorganisation.

This painting of John Berkeley Monck (1769–1834) was made by Richard Jones. Today, it is part of our art collection. (REDMG: 1996.226.1)

Robert Snare was a well-known Reading publisher. He was a printer in Minster Street and in 1816 he published A History of Reading by John Man. Jørgensen himself was a prolific writer throughout his lifetime, writing accounts of his life and his travels, meditations on philosophy, and political tracts.

The Stephens were a Reading brewing family that went into banking. In 1781, a partnership was formed between William Blackall Simonds (of the famous Simonds brewing fame), Robert Micklem (a draper), John Stephens, and Robert Harris (a mealman). Their office was on the east side of the Market Place, and the building forms Reading’s Market House today.

Leaving Britain

There is something strangely poetical about the rhythm of Jørgensen’s life: how his highs became lows, how routinely surprising it all was, combined with the way that places, people and fates recurred like musical themes with subtle variation and differences, symmetries and inversions.

On the morning of the 8th May 1820, Jørgensen was arrested and accused of theft. He was charged with stealing the bedding, mattress and quilt from a room he was renting and pawning as if it were his own property. In fact, suspecting this had happened, the landlady and a police constable burst in on Jørgensen whilst he was having breakfast, pulled back the bedcover, and found his bed stripped bare.

Whilst the sentence for theft was typically seven years’ transportation, Jørgensen was imprisoned at Newgate Prison instead and was given a relatively comfortably cell. It felt clear that he had a benefactor looking out for him. Their identity was never known, but he had made many friends in high places throughout his time in England (from notables of high society, to the Foreign Office during his time as a spy). In the same way that Sir Joseph Banks had helped him sail to Iceland, it seems somebody else had saved him from a journey to Australia.

In October 1821, Jørgensen was released on parole, with terms that must have struck him as uncanny. As a prisoner of war, the condition of his parole was that he was unable to leave the country. This time he was told that leave he must. He was given one month in which to arrange his exit, effectively managing his own transportation to a place of his choice, and he was forbidden from returning until the end of his original seven-year sentence.

Jørgensen ignored the advice of his parole in 1809, and he did the exact same thing in 1821. He remained in London and evaded the police for almost a year, before being tracked down on the 28th September 1822, when he was returned to Newgate and this time sentenced to death. However, like before, this sentence was to be commuted, and after three further years’ imprisonment, Jørgensen was transported to Tasmania; the place that he had sailed to as a free and much younger man twenty years before.

Jørgensen’s later life and legacy

Whilst much of Jørgensen’s life in England and Europe bore all the hallmarks of a literary rogue, his legacy is a complex one, particularly in relation to the colonial settlement of Tasmania. Jørgensen served as a convict constable in the Tasmanian Field Police, which was heavily in conflicts with the island's Aboriginal people. Later, he participated in what was known as the Black Line: an enormously aggressive policy by colonial settlers that sought to force Tasmania’s Aboriginal population to relocate from their homeland.

By the time of Jørgensen’s transportation, this native population had already been devastated by fifty years of colonial violence, dating back to the first recorded arrival of European settlers in 1772. Much more about this policy and its impact can be learned on the website of the National Museum of Australia. It serves as a reminder of the complex impact and legacy of colonial politics, which are so ingrained within the history of exploration and adventure, and yet have been overlooked for so many years.

In Iceland, Jørgensen is remembered today as Jörundur hundadagakonungur: the Dog-Days King, for his reign began and ended in the dog-days of summer. And whilst it was a short tenancy of the Icelandic throne, Jørgensen proved to be a dog that knew many tricks, and it is remarkable to think of the many ways in which his history crossed with Reading's.

Find out more about Reading's history

Thanks for reading our blog about the life of this remarkable figure from early 19th-century history, and how fate brought him to Reading. For more information about the history of our town and the people that have called it home, check out more reads on the Reading Museum blog.

If you'd like to read more about the Gentlemen Danes and their lives in Reading, buy your copy of The Gentlemen Danes from the Reading Museum shop.

References

- The English Dane, Sarah Bakewell

- The Gentlemen Danes, John Nixon

- The London Gazette (6 September 1814, p. 1822)

- Iceland's 1100 Years: History of a Marginal Society, by Gunnar Karlsson

- The Convict King, James Francis Hogan, available at https://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/pdf/hogconv.pdf

- ‘REVIEW OF NEW BOOKS: A Winter in Iceland and Lapland by the Hon. Arthur Dillon. 2 Vols’ by Henry Colburn, The Atlas (25 January 1840)

- The website of the National Museum of Australia, https://www.nma.gov.au/