Chris Darbyshire, author of 'Hugh Cook of Faringdon, last abbot of Reading'

Hugh Cook, the last abbot of Reading Abbey, was probably born in about 1490 in or near the town of Faringdon, then situated in west Berkshire. He is generally known as Hugh Faringdon, although more correctly should be called Hugh Cook of Faringdon.

Ordained as a priest in March 1511, he rose to the post of sub-chamberlain by 1520. In that year Abbot Thomas Worcester died, and Hugh was elected abbot of Reading Abbey.

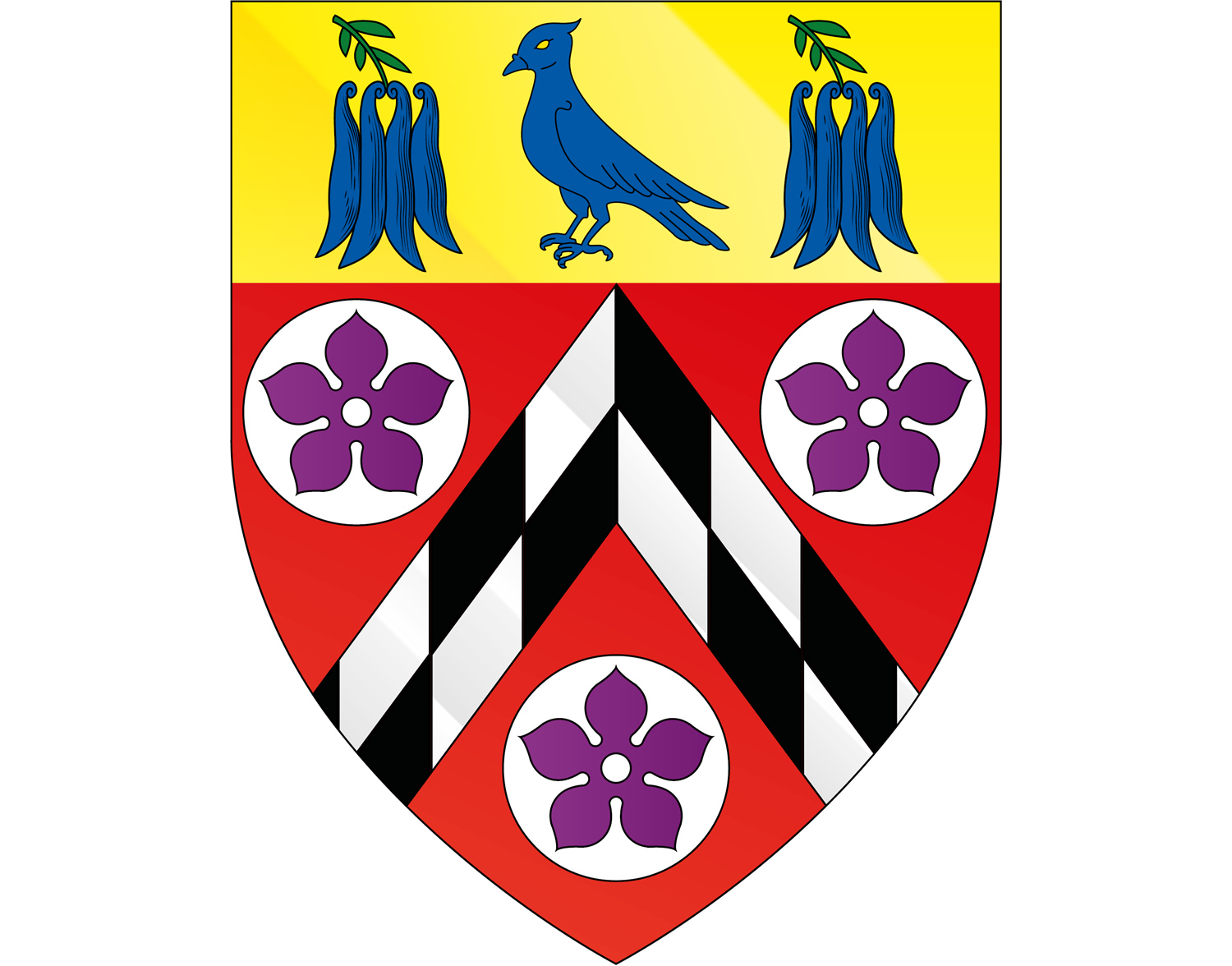

Hugh Cook Faringdon's coat of arms

As abbot, Hugh became a member of the local aristocracy. He was granted a coat of arms, and bought his mother a seat in the parish church of St Laurence in Reading. He was fond of hunting, with deer parks belonging to the Abbey at Whitley and Sonning. He had use of a country house, at Bere Court in the hills above Pangbourne. He was friendly with the king, went hunting with him, and exchanged New Year’s gifts with him.

In 1529, and for the next few years, Henry VIII became increasingly preoccupied with producing a male heir, and with Anne Boleyn. Both matters required that his marriage to Katherine of Aragon be annulled. Hugh, along with other senior clergy, wrote to the pope urging him to accede to the king’s request. Hugh also lent Henry books from the Abbey library to enable the king’s case to be prepared and presented to the pope. The pope did not agree to an annulment.

Henry bullied the clergy until in February 1531 Convocation accepted that Henry was “so far as the law of Christ will allow supreme head” of the church in England. The intention of the clergy was to accept that the king was head of the church in England in temporal matters, but not in spiritual matters.

By 1533 the marriage with Katherine was declared null and void. In March 1534 the pope declared that that marriage was in fact valid. Parliament then passed an act confirming the nullity of the marriage and requiring the swearing of an oath accepting that fact and the validity of the marriage to Anne Boleyn. Hugh, together with the Archbishop of Canterbury and several other abbots, swore that oath and accepted the royal supremacy. There followed a number of visits to religious houses, in which Glastonbury (certainly) and Reading (probably) further acknowledged the royal supremacy.

The pope suppressed by King Henry VIII © National Portrait Gallery, London

As part of the attack on the monasteries, visits were made in 1535, to value the various houses and to seek out any misbehaviour in them. Reading was valued as the second wealthiest rural abbey (after Glastonbury) and the fifth in the country overall. No evidence of any lack of piety at Reading was recorded.

In October 1536 there were rebellions in the north of England, whose objects (among other things) were to roll back the religious changes, to restore papal supremacy, and for some suppressed abbeys to be restored. Hugh must have been trusted by the authorities to be loyal to the crown, as he was asked to investigate any potentially treasonous behaviour at Reading.

Hugh continued in royal favour into late 1537. On 12 October, Queen Jane gave birth to Edward, Henry’s long wished for male heir, but she died twelve days later. Hugh as royal chaplain officiated at the two funeral services for the queen.

In 1538, Hugh appointed Thomas Cromwell to the office of Seneschal, or High Steward, of Reading, no doubt in an attempt to get favour with the Chancellor. Later that year, Greyfriars Priory in Reading was surrendered, and the Abbey visited. Hugh surrendered the holy relics held by the Abbey (including the hand of St James), and they were locked up behind the high altar of the Abbey. Cromwell’s agent, Dr London, tried to persuade Hugh to surrender the Abbey to the king, and seems to have thought that he would be successful, but he was not. London did concede that under Hugh, the religious life of the Abbey was properly conducted.

At some time in early 1539, Hugh instructed the Prior of Leominster Priory (a daughter house of Reading Abbey) to surrender the Priory to the king, but the prior failed or refused to do so.

On either the 7 or 8 of September 1539, Abbot Cook was arrested, and taken to the Tower of London. The Abbey was possessed by agents of the king. He remained in custody until his death. The Abbey was deemed to have been dissolved (closed) on 19 September.

The abbot Reading (sic) to be sent down to be tried and executed at Reading with his complices.

- Thomas Cromwell – October 1539

By royal writ, a court was established to try Cook, and two fellow priests. Hugh was charged with high treason, in that he had denied the supremacy of the king over the church in England.

The trial took place on Thursday 13 November 1539. It took less than one day. All three were convicted, and sentenced to death by being hanged, drawn and quartered. The sentences were carried out on either the 14 or 15 November. The three men were dragged on hurdles around the centre of Reading, then each hanged, but cut down while still alive. At that point they were disembowelled, and afterwards beheaded and their bodies cut into quarters, which were placed around the town and abbey.

Martyrdom of Hugh Faringdon, Last Abbot of Reading in 1539 (Reading Museum)

The motives of the authorities in pursuing Cook, and also Richard Whiting, abbot of Glastonbury, are not clear. The offences alleged are from over two years previously. There is no evidence that any of the men had been ostentatiously denying the royal supremacy. Claims were made shortly after their deaths that they had supported the northern rebels (in 1536, three years earlier), or those involved in the Exeter conspiracy (in late 1538). In all probability the motive was to persuade those abbots refusing to surrender their houses that they should do so, or they might face a fate such as that inflicted on Cook and his fellows. Many of the wealthiest abbeys, predominantly Benedictine, had not surrendered by the time of Cook’s arrest, but all major houses had succumbed by April 1540.

Chris’s newly published book on Hugh Cook Faringdon is available from Scallop Shell Press.