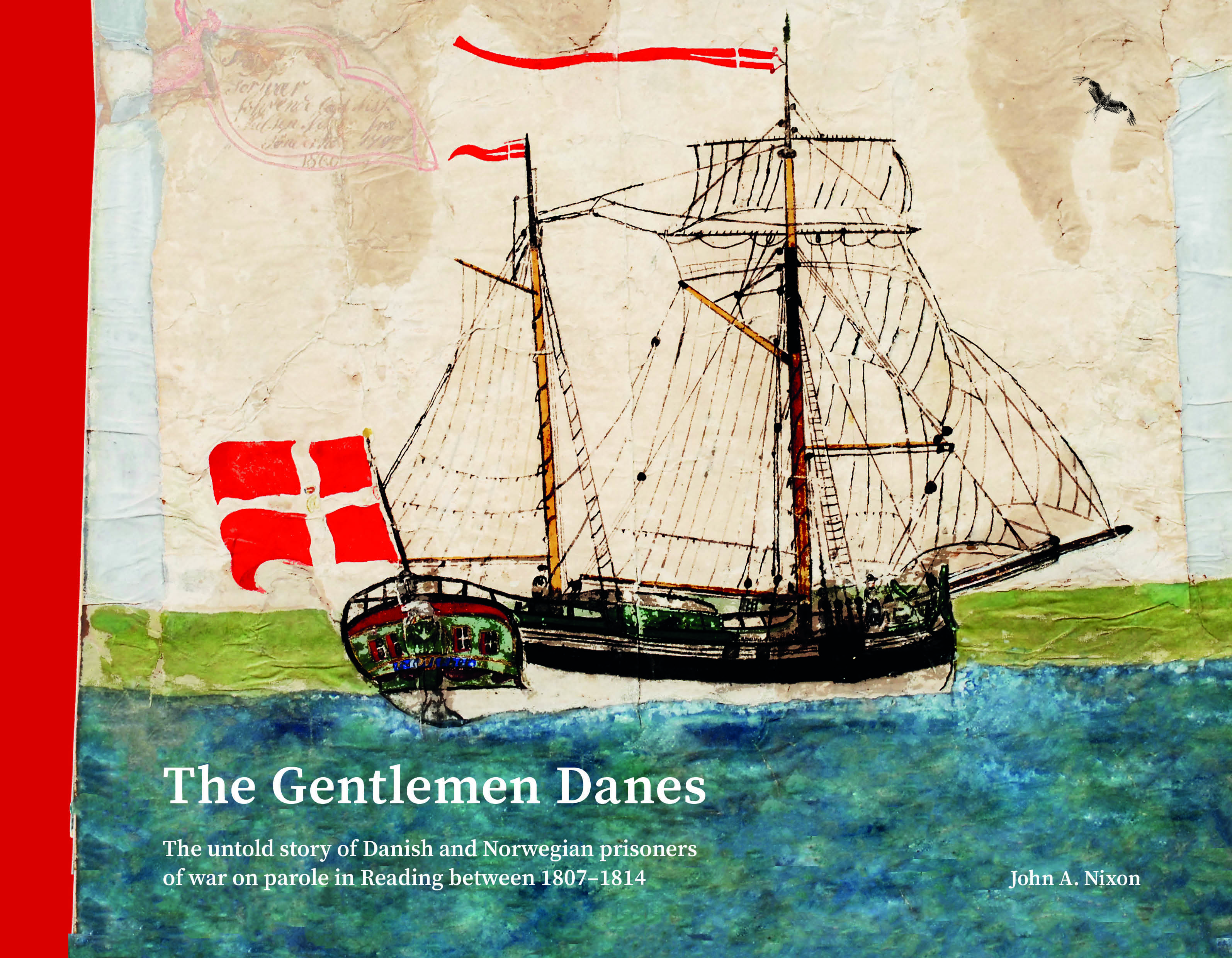

Join John Nixon, author of The Gentlemen Danes, as he shares his latest exciting discovery in the story of the near 600 Danish and Norwegian prisoners of war who lived in Reading ‘on parole’ during the Napoleonic Wars.

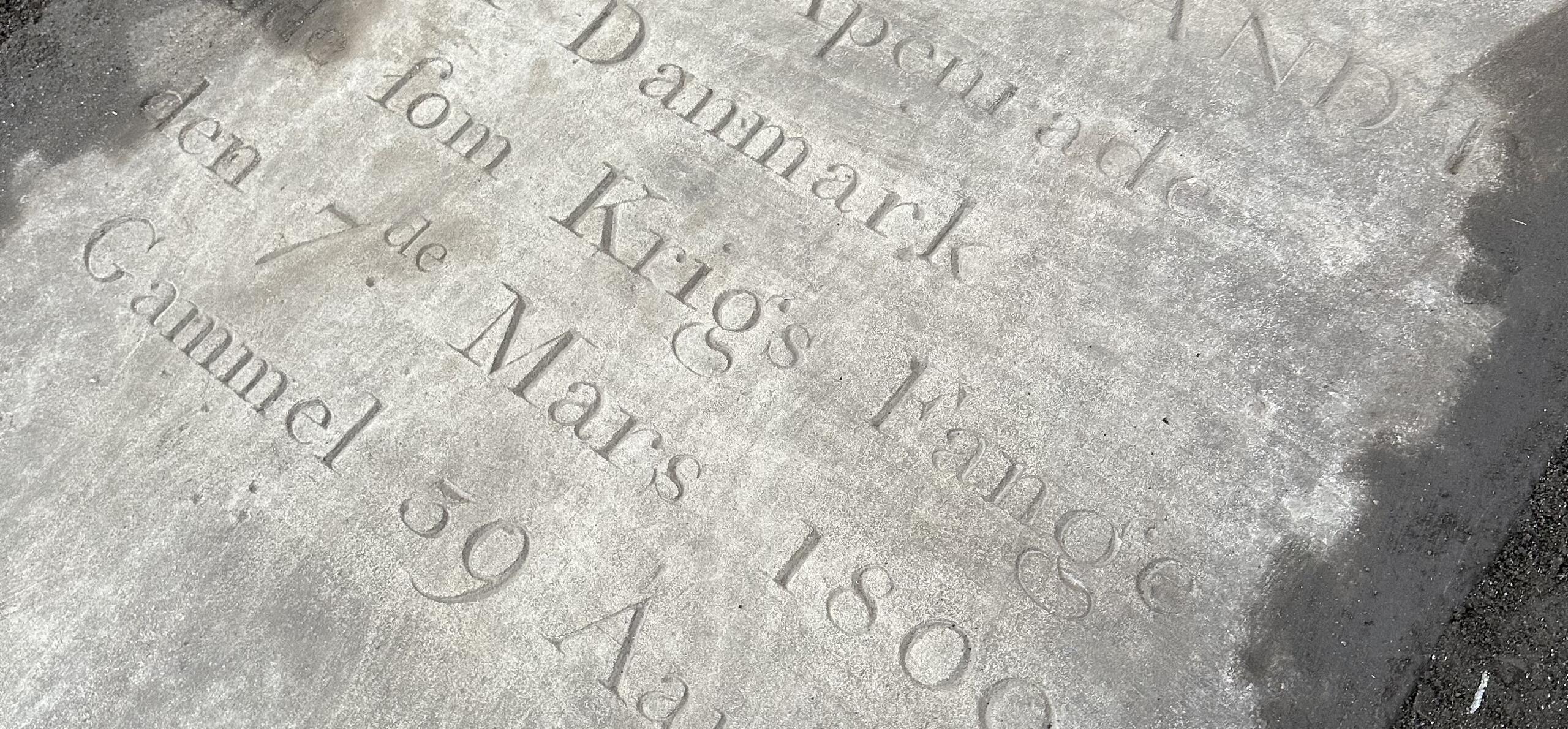

In September of this year, acting on a tip-off, I discovered the gravestone of a Danish prisoner of war directly behind Reading Museum in St Laurence’s churchyard. Lying unknown for decades under an inch of soil, it is dedicated to Marcus Brandt, a ship’s captain, who died in Reading over 200 years ago in 1809. Marcus Brandt was one of nearly 600 Danish and Norwegian prisoners of war who lived embedded in the Reading community ‘on parole’, between 1807 and 1814 during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). His gravestone is the first to be discovered of the seven men who died during this period, and, after the memorial tablet hanging on the south facing wall of St Mary’s Church to another prisoner, Laurentius Braag, only the second verifiable object in Reading to be associated with this fascinating episode of the town’s history; one that has until recent times been largely forgotten.

An image of St. Laurence churchyard and Hospitum looking towards Reading Museum and Town Hall.

Prisoners of war – The Gentleman Danes

Nearly all the prisoners were merchant seamen - skippers, first mates and a few ship’s boys, plus a sprinkling of military officers. These merchant sailors were innocent victims caught up in the conflict between the union of Denmark-Norway, a French ally, and Great Britain called The Gunboat War (1807-1814). Many just happened to be in a British port when war was declared and saw their ships seized and sold off, along with their cargos, as ‘Prizes of War’. Many of their ships did not have war insurance and their skippers, who often owned their own boats, lost everything as a result.

And yet, these were the lucky ones. Ordinary sailors, who made up around 90% of prisoners, were to endure a miserable existence, sometimes for years, on board overcrowded and unhygienic old navy hulks anchored at Plymouth, Portsmouth and Chatham, suffering all kinds of deprivations and disease in the process. Many never saw home again.

Skippers and first mates, however, were considered to be ‘men of rank,’ i.e. ‘gentlemen’, and were allowed to spend their time in captivity on land, having signed a document called a ‘Parole Pass’ which stated that on their honour they would abide by a set of conditions including not attempting to escape. They became affectionately known by the local populace as The Gentleman Danes. As a parole prisoner, men were expected to find and pay for their own accommodation and, if they did not have private means, find work, too. To facilitate their needs, each town had an agent, appointed by the Transport Board, a branch of the Admiralty, which also dispensed a small weekly allowance.

A prisoner’s life in Reading

Reading was one of fifty towns and villages up and down the country that housed parole prisoners. Always at least one day’s march from the coast, and spread out to avoid uprisings, most towns held French prisoners, such as nearby Wantage, Thame and Odiham. Danes and Norwegians were kept at Ashburton and Moretonhampstead in the south west, at Peebles in the Scottish borders and at Northampton in the south midlands. But by far the largest number of the approximately 1000 parole prisoners came to Reading.

Why Reading became a parole town is not known for certain. However, before the first Danes started arriving at the end of 1807, Reading had previously seen two separate small groups of high-ranking French and Spanish prisoners come and go, including the most famous of all the French prisoners, the defeated commander at the Battle of Trafalgar, Vice Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve. It is believed that Villeneuve came up to Reading with his entourage from Bishop’s Waltham, Hampshire, in order to attend the funeral of his opponent, Vice Admiral Lord Nelson at St Paul’s Cathedral in January 1806. It could well be that once the machinery had been put in place to accept and administer parole prisoners, by appointing an agent etc, it was only matter of time before more men started arriving. The fact that they happened to be Danes is purely incidental.

Although nearly 600 prisoners came to Reading in total over the seven-year period 1807-1814, there were never more than around 200-300 in the town at any one time, with many being repatriated after just a few months, especially the ship’s boys.

Living as a parole prisoner meant that these men were able to go about their lives as local citizens, but not allowed to go beyond the town’s limits. This restriction was soon turned a blind eye to by their mild-mannered agent, Mr Herbert Lewis, later to become mayor of Reading in 1825, as was the order to obey a nightly curfew. Thus, prisoners drank in the local pubs of an evening, went for long country walks, some joined local Odd Fellow and Freemasonry lodges and some young officers and cadets even formed a weekly dancing club in a cellar with their washerwomen’s daughters, where they would drink weak punch and be chaperoned by one of the washerwomen. At least three marriages are recorded in local parish records, including one of the naval cadets from the dancing club marrying his washerwoman’s daughter.

Sadly, but not unexpectedly, with such a large body of men, some of them died over this seven-year period. Not much is known as to their causes of death, as this information was not recorded in the ledgers kept by Mr. Lewis, however from a report in the weekly newspaper the Reading Mercury, and the writings of local writer William Silver Darter aka ‘Octogenarian’, we do know that two of these were by suicide.

The gravestone of Marcus Brandt, Danish sea captain and prisoner of war, soon after its discovery in September 2023.

Laurentius Braag

The first of the seven to die was a merchant from the Danish West Indies, (now the US Virgin Islands), called Laurentius Braag, who died in September 1808. His death prompted agent Herbert Lewis to write an appeal in the Reading Mercury, to raise funds for the prisoners. In total, nearly £200 was raised in four tranches over several months. The lists of contributors, whose names were published in the paper, read like a ‘Who’s Who’ of Reading society at the time, with names such as Blandy, Simeon, Valpy, Monck and Liebenrood among them.

Laurentius Braag is remembered in a plaque hanging on the south-facing wall of St. Mary’s church in central Reading. An early photograph of the church taken in 1844 by Reading-based pioneer of photography, Henry Fox Talbot, plus several engravings, reveal that, at least during the first half of the 1800s, there were in fact two identical plaques placed next to each other. Which prisoner the missing one was dedicated to and the cause of its disappearance can only be speculated about. We can be certain though that both men are buried somewhere in the churchyard. However, as there is no burial plan, it is impossible to know where these graves are located. The same is true of St. Giles, no burial plan exists.

St Laurence’s churchyard

This lack of a plan would have also have been the case with the third of Reading’s three main churches, St. Laurence, had it not been for the sterling efforts of volunteers from the Berkshire Family History Society, Reading branch, back in the mid-1970s. Alarmed by plans to build an eastern section of the Inner Distribution Road (IDR) that would have sunk a motorway-sized road between St. Laurence churchyard and Forbury Gardens, they set out to map the churchyard in the spring of 1975 before large parts of it were destroyed. Writing in April 1978, Treasurer and Membership Secretary Jackie Blow states; ‘When we first set out we did not quite realise how great was the task we were about to let ourselves in for, and it took many, many afternoons to complete all 390 tombstones’.

Nearly fifty years later, we have to be very grateful that they stuck to their task. For had the fear of seeing a large part of St. Laurence’s churchyard sliced off to make way for a thankfully unbuilt section of the IDR not spurred the society into action , it is absolutely certain that this significant gravestone would never have been discovered. The project’s findings are now kept at the Royal Berkshire Archives, and feature a list of all inscriptions that were still legible as well as, most importantly, a map. Its reference number is: DEX1049 - Survey of graves in St Laurence's churchyard, Reading.

The search and the discovery

Until early September 2023 I was not aware of this file’s existence. After I had learnt that there was no burial map for St Mary’s, I had assumed that the same was true for the other two churches. Then I received a tip-off from Reading history buff, Evelyn Williams, after she had come across this piece of research at the archives. Listed as grave no. 42 was a tombstone written in Danish! This was so exciting, I had to find it!

A few days later, on the 14 September, I turned up at St Laurence’s confident I would find the stone, but it was nowhere to be seen! I retreated to The Pantry Cafe nearby, and over a cup of coffee began correlating the grave numbers with the map before heading back to start looking again.

Under a yew tree I stood on a large patch of brown earth, and referencing from other gravestones on the map, I thought ‘well this is where it ought to be’. I started to move my right foot from side to side in the soil. Soon enough a stone surface appeared. I kept moving my foot. Some very well-preserved inscribed letters began to appear. Then I scraped a bit more and could see that it was in Danish. This was it, hidden under a couple of inches of soil! Translated the inscription reads, ‘To the memory of Marcus Brandt born in Apenrade in Denmark Died as a prisoner of war 7th March 1809 Aged 39 years’. I am not sure this can be classified as archaeology, but what is certain is that this is a very important discovery indeed. It is the first known grave of a Danish POW in Reading to be found and most likely the last due to reasons outlined above. Furthermore, it might be the only known gravestone of a Danish POW in the whole country.

Four Danes standing by the gravestone of Marcus Brandt on October 14 2023 during a Gentlemen Dane’s walking tour for the Mayor of Reading, cllr. Tony Page.

Who was Marcus Brandt?

So, who was Marcus Brandt? In the two Transport Board ledgers kept for the prisoners by Mr Lewis, Marcus Brandt (sometimes spelt Markus, the letters c and k being both used interchangeably), is recorded as Prisoner no. 360, master of a ship called Triton, that was taken as a “Prize of War” on 24 September 1807. He is described as 39 years old, 5ft. 7 in. tall with light brown hair, blue eyes, long face, of a fresh complexion and slender build. Furthermore, he had a distinguishing mark on the left eye. This information was recorded to help identify absconding prisoners. Further information is provided by the inscription on his gravestone.

The name of his birthplace is given as Apenrade, which is the German spelling for a small port town located on the east coast of southern Jutland, only a short distance north of the border with Germany. The town is now known by its Danish spelling of Aabenraa. This detail could indicate that he was a native German speaker. This supposition is given support by the fact that genealogical records show that his father was called Heinrich, the German name for Henry (in Danish it is ‘Henrik’). None of this is unusual. Even today, there is a German-speaking minority living in southern Jutland, just as there is a Danish-speaking minority living in northern Germany. Another clue as to his possible German heritage is that on the stone, words containing the Danish vowel ø have been replaced with the German ö instead.

As to his status as a merchant skipper, there is information available on the Danish version of Wikipedia that contradicts this and suggests that he was in fact the captain of a Danish Navy warship, and to back this up, it is known that a Danish frigate called Triton was taken by the Royal Navy at this time, coinciding with the Second Battle of Copenhagen (1807) and its aftermath. The Wikipedia page entitled, “København bombardement og konfiskation” states that “six members of the crew originating from Aabenraa were taken into British captivity; three on the prison ship Niger in Plymouth and the rest in the land prison of Reading, west of London, including the skipper Marcus Brandt”.

Although this assertion has been disputed by leading Danish naval historian Søren Nørby, and is backed up by the fact that Brandt’s name does not appear in the official record books of Danish naval officers, the ledgers kept by Mr Lewis do indeed list two other members of the Triton coming to Reading, prisoner number 375, ship’s boy J C Kock and prisoner number 387, first mate, B C Cock (no doubt his father) as described in Danish Wikipedia. Hopefully, in time, it will be possible to discover whether Marcus Brandt was the master of a merchant ship or a warship. I intend to continue researching this matter. Watch this space! In the meantime, if you are in Reading, please go along and see it .

Discover more about The Gentleman Danes

For the full story about the Danish and Norwegian prisoners of war in Reading, John’s hardback illustrated book, The Gentlemen Danes, can be purchased in our museum shop or at Four Bears Bookstore in Caversham.

You can also contact the author directly by email.