The artworks in our latest exhibition, Abstract Art, are drawn from the museum collection and illustrate some of the many approaches to producing abstract work.

In this blog, join Reading Museum’s Art Curator, Elaine Blake, as we introduce the exhibition, explore abstract art itself, and suggest how you might engage with the many works on display.

How do we engage with an abstract artwork?

Abstract art can seem offputtingly difficult so I believe it's worth approaching it in simple terms.

When you look at narrative images – that is images that tell a story or suggest a scene – there are two parts of your brain working quite independently.

The first part is the part of the brain that's hard-wired to spot people or structures. If you look at something abstract like a piece of marble or a tree trunk you'll find faces in the bark because part of your brain is always looking for them. There must be some evolutionary reason for this automatic response to any complex surface or form.

At the same time, a whole different part of your brain is operating on a subliminal level relating to judgement. When you look at any artwork, your first response is likely to be whether you like it or not. What underpins that is your brain questioning things like is it harmonious? How do the colours work and mix? How do the shapes and lines suggest space in and around the work?

Arches II by Johannes von Stumm

Most of the time, these are not questions that we are aware of, but they are things that artists think long and hard about as they make works.

Unlike narrative art many abstract artworks simply focus on that picture-making itself and we can too.

In the mid and late twentieth century, artists spent a lot of time discussing and theorising as they their work moved towards this more conceptual level. They were much less concerned with the traditional sense of pictorial representation. They chose not to describe the world as we see it but instead focus on the building blocks that make up images, reminding us of fundamental aspects of our world. In this way, they resemble music or poetry.

How modern is abstract art?

It’s worth remembering that while abstraction and abstract art have been popular since the 1960s, abstract images have been important throughout history and to cultures around the world. Think of the earliest cave paintings: though there were drawings of people and animals, there were also patterns and abstract shapes, and these equally reflected the observations and perspectives of the artists.

Can there be such a thing as abstract art?

There is a real question whether there's such thing as a truly abstract artwork. You could say that any artwork is abstract: every piece of art follows a process of manipulating colours, shapes, and forms and materials. It is equally true that today, in a post-conceptual world it is hard to encounter abstract artworks without looking for self-references by the artist or asking whether the painting is the artwork at the end of an exploratory process by the artist, or if that process was as much the artwork as the finished piece. Furthermore, by engaging with the work are you changing it into your own artwork? Do abstract artworks challenge us to reflect on how we respond to them as we study them and ask us to add our own ideas – our interpretation. Profound thoughts indeed!

Abstract Art exhibition at Reading Museum. In the foreground is 'Vestige' by Halima Cassell

What are abstract works about?

When an artwork is finished, it takes on a life of its own. It adds a layer of interest to think about what the artist was intending, and whether they intended anything in particular, but it’s not essential. Often works are ‘untitled’ so that you are not led to think about their content and even when there is a descriptive title it has often been added after the work has been finished. I think abstract art can be hard because it requires engagement, patience, and exploration. The artwork can be explored as a thing.

Much abstract art communicates simply on an emotional level. Notice the dynamic energy of a piece held in balance by the play of light and dark, the arrangement of tones, lines, and forms with their edges, planes, and textures. Let your eyes roam around the space. This is what these artworks are ‘about’. It’s also why quite a lot of abstract artworks are so big. It's more like performance, like a big light show. So big that you are within it, and you feel the energy created. That’s a feeling that we’ve looked to recreate within the gallery.

Is abstract art important? Who is it for?

This sense that abstract art is purely about the art – and not about stories or knowledge of the world beyond it – is important in modern history. At the turn of the twentieth century, the great pioneers of Western abstract art were politically motivated. They wanted to make a type of universal art that was for everyone. Art that you didn’t need to know about religion, history, or mythology to appreciate, and art that reflected the modern world. This idea was shockingly new at the time, but finds much greater appreciation today.

Abstract art: for everyone

There are different kinds of abstract artworks throughout the Abstract Art: for everyone exhibition. To help explore the artworks, we have displayed some questions around the gallery that you can choose to use as nudges and prompts for your own reflection. These can be applied to all the paintings and the works on display.

It is very easy to simply say I like it or I don’t like it and move on to the next piece. But exploring these artworks is an experience that is rewarding if you give it time and attention. It can become a very contemplative and mindful experience.

The exhibition is very different to our previous two – COLLECTED: 150 Years of Reading FC and The 1971 READING FESTIVAL: For the First Time – which brought clear stories from Reading's past. In Abstract Art, the tempo is much slower, and for that reason we have placed seating throughout the gallery including carrying seats so that you can sit wherever you feel you get the most from the works. We really encourage you to take your time and to think about how different pieces relate to others – they have been carefully arranged so that sometimes the texture, colour, the approach plays off nearby works.

How can you start exploring?

There are some simple things to consider as you move from piece to piece. Try approaching them in the same way that you'd think about the museum objects throughout the other galleries.

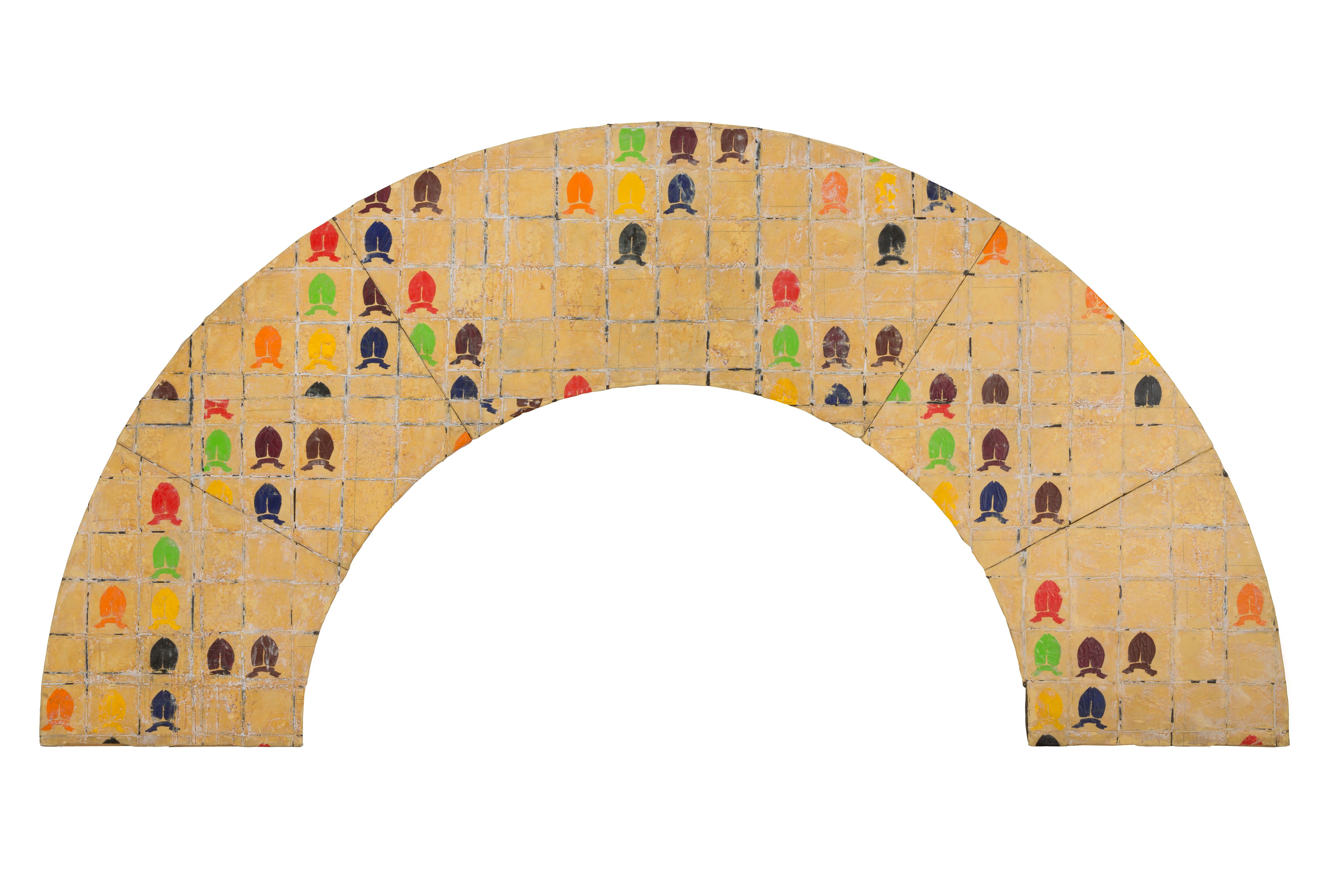

A useful starting point is thinking about how the piece could have been made and then going on to think about why the artist might have chosen to make it in this way and finally to think about what it could mean for you, what it makes you think about. For example, in the gallery there's the Steven Buckley arch, Tarantara. You might think: oh, that looks like a pattern on a wooden arch. But if you look more closely, you'll spot that it's in five pieces. It doesn't have a frame. It's stood on the floor. It's not just an image, it’s a painted thing, even a sculpture. And if you look closer still, you'll see that it's not painted on a flat service, but on strips of canvas, stapled together. It's a patchwork collage, created by combining bits of old paintings that have been repainted. Buckley has used something called encaustic, an ancient painting technique used in Roman coffin portraits, a complex way of suspending pigment in wax. You’re led to wonder: why did the artist choose to do this? There's a bit of white blooming on the surface which will change over time so did he deliberately include its gradual disintegration in his work?

Tarantara by Stephen Buckley

And you may think: so what? But it's interesting and rewarding to wonder about the hows and whys and in doing so make your own interpretation , your own art work. The patterns are in fact stencils, resembling the shapes of bishops mitres so is the thing connected with a game (chess?). Why have they been put where they've been put? They look random. Buckley rarely says anything about his works but he has said that the stencils were placed on the roll of a dice. But you don’t need to know that. There is no need to guess right answers to these questions. All we would encourage, if you would like to, is to simply think about them and explore the artworks at your own pace.

Abstract Art runs until 19 August 2023 in the Sir John Madejski Art Gallery at Reading Museum.