'You don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone'

In our first blog exploring the history of Castle Street and St Mary's Butts, we halted our walk through time in the 18th and 19th centuries, just as Reading was beginning to prosper as an important market town at the centre of an agricultural hinterland.

Here, join us as we pick up those threads in part two, and continue with our journey before moving to the more recent period of the town’s history.

(Blog kindly guest-written by Katrina Parker and Margaret Simons of the Reading Conservation Area Advisory Committee).

St Mary's Butts

Changes to the St Mary’s Butts area, as already mentioned, had begun in the early part of the 19th century with the removal of buildings from the south side of St Mary’s churchyard and the changes to the road level in Gun Street. The distinct mix of post-medieval building juxtaposed with that of the 18th and early 19th century was a blend of commercial, retail and residential property providing goods and services to the population.

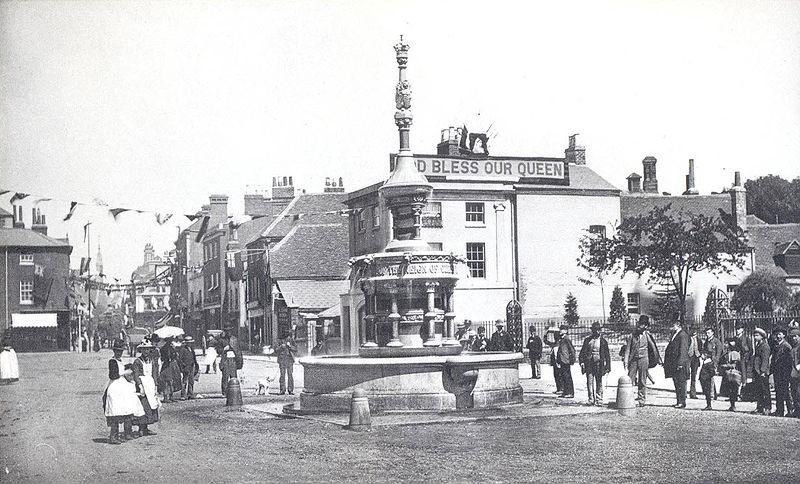

St. Mary’s Butts, Reading, looking northwards, c. 1895 (courtesy of Reading Library’s Local Illustration Collection)

On the west side: nos. 18 and 17 (corporation weighbridge); nos. 16 and 15 (fire station); no. 14; no. 13; no. 12; no. 11 (Thomas Lock, carman and horse dealer); no. 10 (James Goodacre, pawnbroker). On the east side: the signs for no. 59 (John Powell and Son, chemists) and no. 57 (Allied Arms Inn) are legible. 1890-1899, photograph by Walton Adams.

However, as the 19th century progressed, there was plenty for the local public health reformers to focus on in the area. Improvements were seen as necessary to sweep away the insanitary and slum dwellings that they felt posed a threat to the health of all who lived there. The parish of St Mary's and Reading Corporation were assisted in their work by local surgeon Isaac Harrinson (not Harrison) who lived in Castle Street. His munificence, which extended to thousands of pounds, helped to extend and improve St Mary’s Church, restore the organ during the 1870s and aid the Corporation in its work to clear the offensive buildings, particularly Middle Row 1886/7, which stood at the southern end of the Butts.

Much improvement work had been completed by Queen Victoria’s jubilee year in 1887. To mark the achievement and the contribution made by Isaac Harrinson, a testimonial was organised. Designs were drawn up and Harrinson, himself, chose the one by Reading architect Mr S. Slingsby Stallwood. In December 1887, subscribers met at St Mary’s Church for the unveiling of the Churchyard Cross, carved by Messrs. Wheeler Bros. This still stands today and is a listed monument. [1]

Churchyard Cross (Sean Duggan)

Queen Victoria Jubilee Fountain

St Mary’s Butts 1887 (Courtesy of Reading Library’s Local Illustration Collection)

In June 1887, to designs by G.W. Webb, the Jubilee Fountain celebrating Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee was formerly unveiled.

The oval three-stage fountain, with drinking bowls, had water pouring from the mouths of eight gargoyles at the lower level, twenty smaller jets of water at the middle level, and finally a jet of water gushing from the crown and coronet at the top. The fountain was commissioned by the Borough Extension and Improvement Committee at a cost of £400 and was awarded to the contractor Messrs. Wheeler Bros.[2] A subway was constructed under the fountain to allow for access to any portion of the structure should it be required. Sadly, the fountain ceased working and the lowest and largest basin was transformed into a planter, which is as it remains today.

Victoria’s Jubilee Fountain (Author)

Castle Street

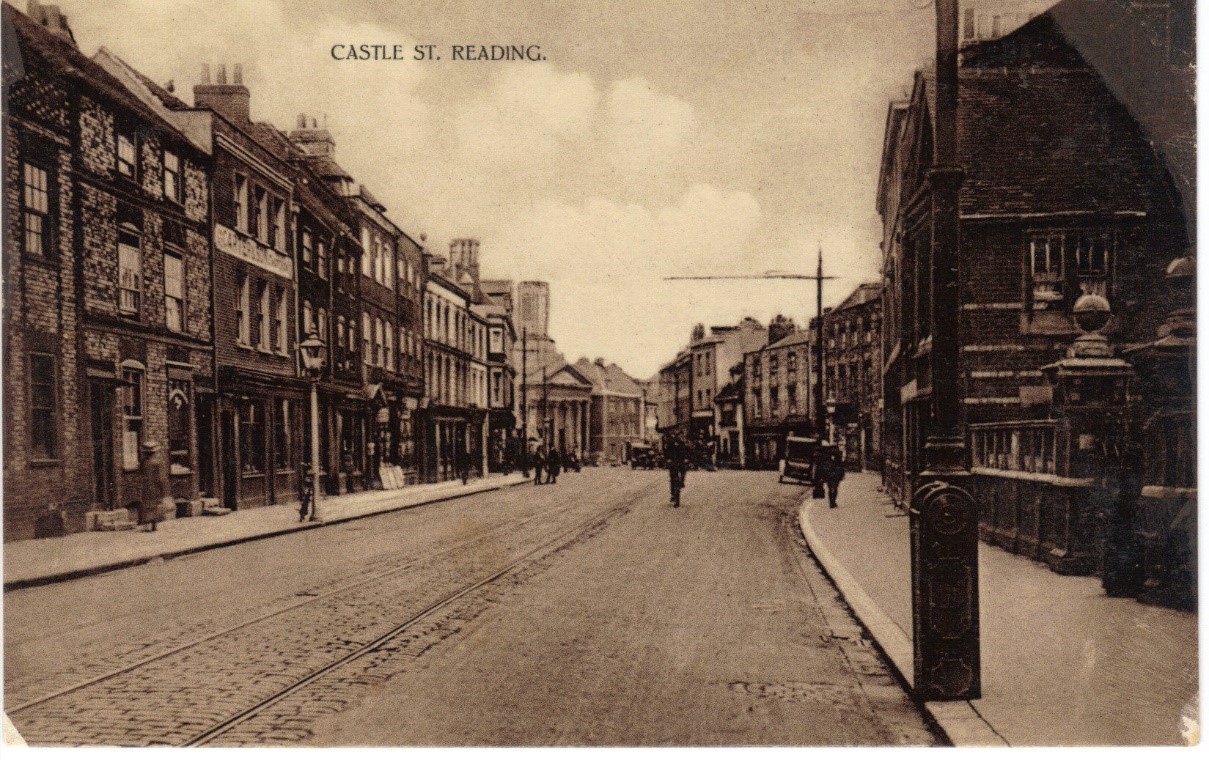

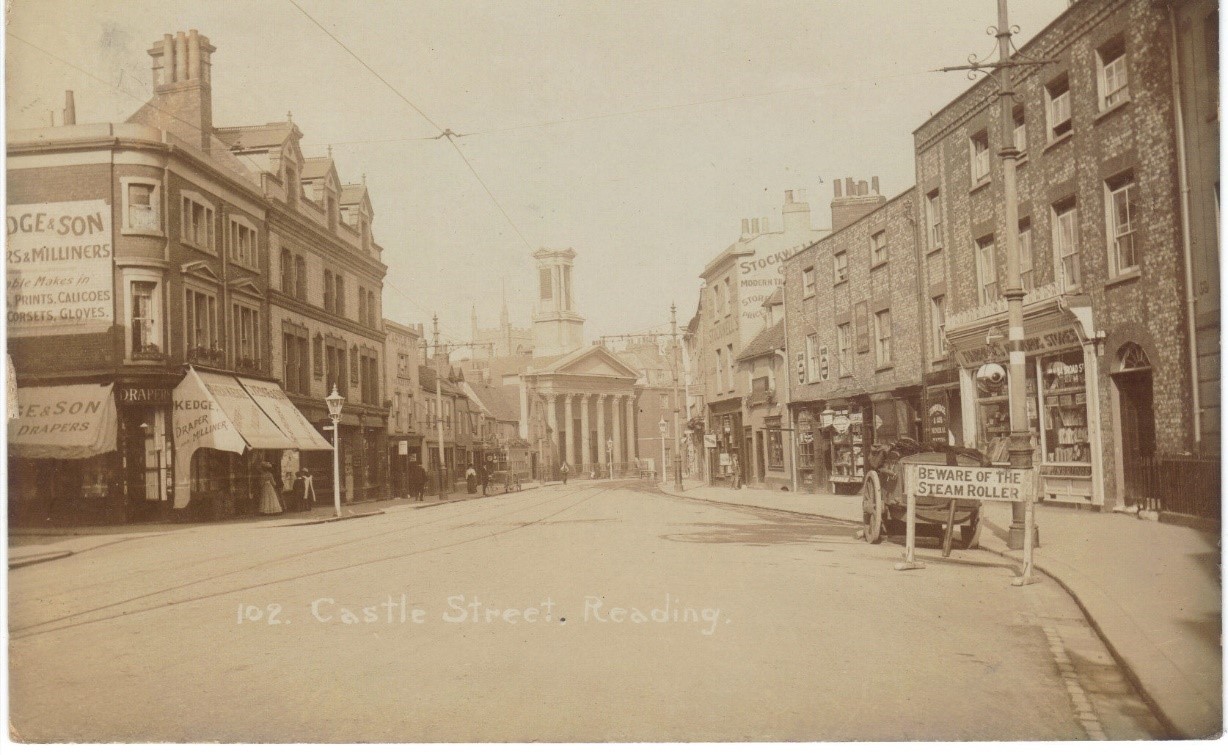

North and south sides of Castle Street c.1900s, taken from just inside the modern day IDR, Vachel Almshouses entrance in foreground on right hand side (Sean Duggan)

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the north and south of Castle Street were lined with a mix of residential and commercial properties. It was a busy shopping street serving a densely populated area of the town. Between The Horn and St Mary’s Episcopal Chapel are the only three remaining period buildings on the north side (all listed). Behind no 8, out of sight is a very early 17th century cottage, which is also listed.

On the south side of the street, there is still much building of the period. From nos. 3 and 5, to no. 63 (Holybrook House), including the culvert to The Holybrook (at the rear of the Vachel Almshouses), there are only three buildings that are unlisted: nos. 41 and 57 (which were both built in the 20th century) and no. 31. No. 31 was listed until 20th November 2018, when it was delisted because:

‘despite having C18 origins, the cumulative effect of a number of substantial alterations has resulted in a building that is constructed mostly of C20 fabric; * key internal fixtures, notably the staircase and fireplaces, have been removed in the C20.’ (Heritage Gateway)

East end of Castle Street at junction with Boarded Lane c. 1900s (Sean Duggan)

Here is just a small sample of what can still be seen today.

Holybrook House, 63 Castle Street

Certainly, one of the most desirable and imposing residential properties, no. 63, dates from about 1750-1760. It was probably built for a Reading tradesman named John Spicer, three times mayor of the town. The first paving stone, from works by the town’s newly formed Paving Commissioners to pave Reading’s footways, was laid here before the door of the mayor’s house on the 8th August 1785.

Moreover, the house has a tradition as being a popular residence for the town's mayors. At the time of his death in 1881, it was the home of William Exall, of the Reading iron foundry firm Barrett, Exall & Andrewes. Mayor and department store owner William McIlroy lived there and his son William Jr. was born there in 1893. He also went on to become mayor in the late 1930s and during WW2.

Between WW1 and WW2, the Workers' Educational Association, whose aim was the promotion of higher education among the working classes, occupied the house. Their warden, T. W. Price, wrote a book about the WEA in Reading 1903-1924.

In the 1970s, the Inner Distribution Road was driven through Castle Street, flanking Holybrook House.

One significant improvement to the building, has been the removal of many of the ugly downpipes from the façade of the building. It is now offices to several companies, but some original features have been retained.

Holybrook House and Construction of IDR. (Sean Duggan - Photographer Sidney Gold)

St Mary’s Episcopal Chapel, Castle Street

1890 Castle Street looking eastwards and the distinctive ‘pepper-box’ on church tower, all now removed. Glass negative, Box 19 No. 8137, by H. W. Taunt. – (Courtesy of Reading Library's Local Illustration Collection)

On the north side: no. 20 (S. H. Higgs, Lion Brewery); no. 14 (Sun Inn) and St. Mary's Episcopalian Chapel, later known as St. Mary's Church. On the south side: no. 17 (Lyndford House) and no. 19 (Devonshire House).

The 18th century was a time of religious change. And out of dissatisfaction with the Church of England came the Methodist and Evangelical movements.

When the minister of St Giles on Southampton Street was succeeded by a very traditional minister in 1797, the Evangelical members of the congregation left. They raised £2,000 to buy the site of the Old County Goal in Castle Street and commissioned a chapel to seat 1,000 people. Today, it is said to still have one of Reading’s best church interiors. It opened in 1798, with a plain, unadorned street front and no chancel. In 1836, it reconciled with the Church of England. This did not suit a section of the congregation, who left and set up the Congregational Chapel at no. 11 Castle Street.

St Mary’s underwent big changes in the 1840s with a chancel added to the east end and a classical portico front affixed to the original building by two iron tie-bars, which are visible either side of the inner west doors. Above the portico stood the pepper-box, a square bell-tower, which was taken down due to safety concerns in the 1950s.

In the second half of the 19th century, the church added a school at the back, reduced the old box pews and, in 1860, replaced the three-decker pulpit with a high and low pair.

In the 20th century religious change continued at St Mary’s. The General Synod of 1992 caused the minister and congregation to leave the Church of England in 1994 and associate themselves with the Continuing Anglican Movement whose worship is based on the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

Remaining buildings north side of Castle Street (Wikimedia Commons: Tom Bastin)

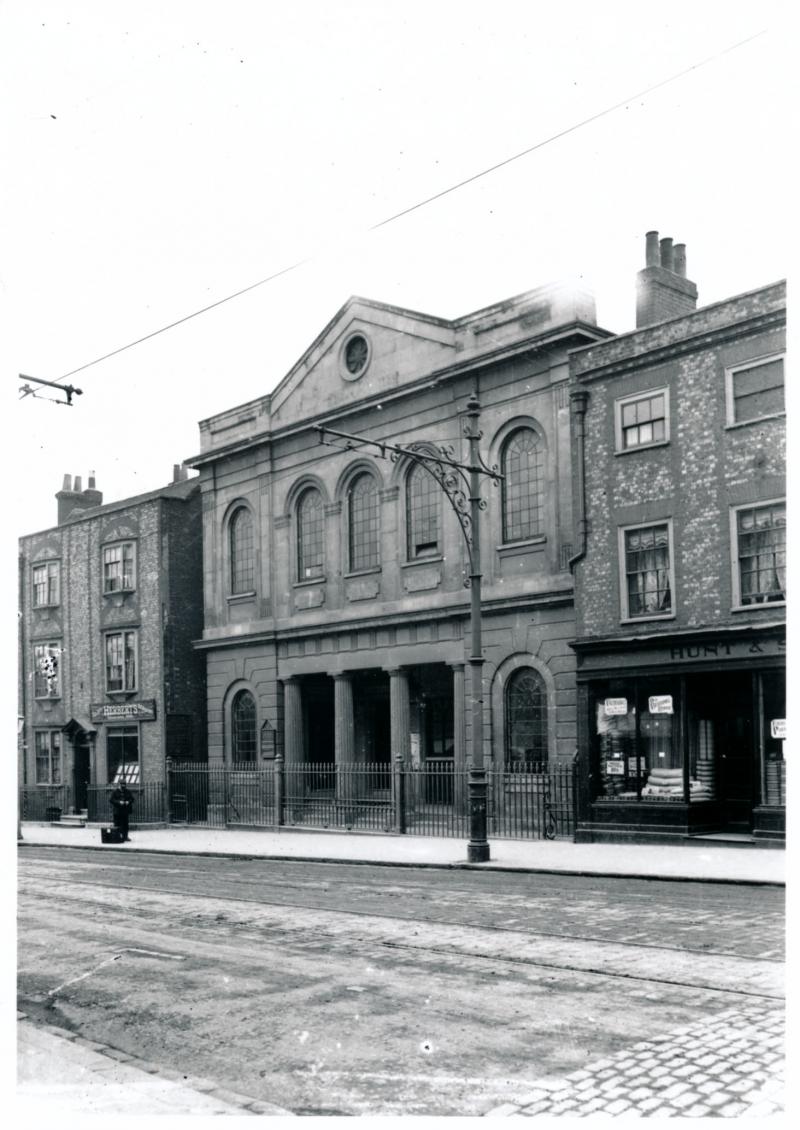

11 Castle Street - former Congregational Church

Congregational Chapel (Courtesy of Reading Library’s Local Illustration Collection)

Castle Street Congregational Church was formed in 1836 when the Church of St Mary's reverted to the Church of England. Those members who wished to remain Independent at first rented rooms in Bridge Street and, in 1837, built a Congregational Chapel in Castle Street, almost opposite their former church.

In 1886, the church amalgamated with the Augustine Church in Friar Street. The church declined in the 1950s, closing in 1956. The proceeds of the sale of the building, and some of the church contents, were given to a new church to be built on the Southcote estate (later Grange Free Church). Since its closure, it has served as a furniture store, a Mexican restaurant/night club before becoming a pub, The Litten Tree, at the beginning of the 21st century. The current owners, Brewdog, took over the premises in March 2018.

The new owners seemed unaware of what is and is not allowed to be done with a Grade II listed building and the restrictions of a conservation area. A 2018 retrospective planning application was rejected for the fascia board, signs and black paint. In 2020, the craft beer company finally began to strip the detrimental black paint off the front walls. The paint was not of the correct type to be used on stone and neither was it an acceptable colour for the Conservation Area. Also refused was the placing of furniture on the public highway.

The exterior of Brewdog, which has been based at 11 Castle Street in recent years (Reading Civic Society, 2018)

Former Congregational Chapel, 11 Castle Street, black paint in process of being removed (Sean Duggan)

20th and 21st Century

Particularly from the second half of the 20th century, much 18th and 19th century building was cleared and redeveloped to meet the changing needs of the town. The clearance of the area bounded by Castle Street in the south, Oxford Road in the north, and St Mary’s Butts in the east (alongside the dissection of Castle Street to the west by the Inner Distribution Road in the 1970s) completely changed the character of this part of town.

Whilst Castle Street is still the best pre-Victorian street within the IDR, this claim is only true of the south side. From the Sun Inn westwards, late 1960s development cleared a space for a Magistrates’ Court (1968) and Police Station (1976). Doing this caused the removal of a mixture of shops, dwellings, businesses, breweries and pubs with lanes that connected it to Hosier Street, which then ran from St Mary’s Butts to Russell Street. With the demolition, an extensive neighbourhood shopping area disappeared and it destroyed the line, scale, form and enclosure of Castle Street, an area that had already been given conservation status. Behind these new buildings is a civic precinct (civic offices from 1975-8, now gone), the Hexagon (1977) and the renamed Broad Street Mall shopping centre (1969-72, which was named the Butts Centre until 1987).

During this period of redevelopment and 800 years after the Abbot of Reading had established his new market in Market Place, Reading market moved again. When it was no longer practical to hold the market in Market Place, it returned to near its original location in Hosier Street, opposite the west door of St Mary’s Church, where it has remained for over 50 years.

Reading Market, Hosier Street, 2012 (Sean Duggan)

The present-day St Mary’s Butts is still a significant thoroughfare. The trams and trolley buses of the 20th century replaced the coaches, carts and wagons of the earlier period, whilst its traffic restrictions today facilitate the operation of Reading Buses for which it is something of a terminus.

Trolley Buses, St Mary’s Butts (Michael Braisher)

It has buildings from 16th century, like the timber-framed construction of The Allied Arms on the eastern side, and nos. 35 and 37 on the west side. Apart from the 17th century Horn public house, all of these buildings are listed. On the north-west corner, are the buildings of (and an entrance to) the Broad Street Shopping Mall. This early 1970s development is 50 years old this year and has had something of a chequered history, with a number of revamps to its name. The 3,000sq ft mall was bought from the Englander group in 2015 by Moorgarth, which in turn is now considering selling. However, during this time, planning permission has been given for a variety of different purposes to allow it to fulfill modern day demands. Although some planning decisions have been held up by the recent pandemic, little has been done and many of its retail units are empty. [3]

Allied Arms (Sean Duggan)

The face of Minster Street was also to change during this time, with the rear entrance to the John Lewis department store, formerly Heelas, now dominating the north side (1979-1985). However, at the junction of Minster and Gun Street is one of the main entrances to the town’s largest retail development to date.

The Oracle Shopping Centre (1997-2000)

On the south side of Minster Street, a large shopping centre along the banks of the river Kennet was developed. It was a much-awaited development on what had been part of the Courage (Simonds) brewery site until 1980. This 22-acre site was developed as an urban response to the trend for out-of-town shopping malls and occupies a site that was once home to a medieval guildhall and mills, dye works, a tannery and an iron foundry. The Minster Street entrance is more or less at the point where its namesake the Oracle workhouse once stood (1628 - 1850) and 15 Gun Street was contemporary with this.

Minster Street entrance to the Oracle Shopping Centre, good example outside no 15 B.B.Q restaurant of the difference between the early 19th century street level and the current level (Sean Duggan)

Thank you

This two part blog was brought to you as part of the High Street Heritage Action Zone programme, a four year project that is being funded by Historic England and Reading Borough Council. A big thanks to our fantastic guest bloggers Katrina Parker and Margaret Simons of the Reading Conservation Area Advisory Committee.

To view more images from Reading's past, take a look at our Online Collections, or visit Reading Library's Online Catalogue or the Berkshire Record Office.

End Notes

[1] Reading Mercury(RM) 24/12/1887 p2; Reading Observer (RO) 7/7/1888 p.2; RM 4/4/88 p5.

[2] RO 18/6/1887 p.2.; RM 26/2/1887 p.5.

[3] Mall tight-lipped over reports of sale - UK Property Forums 10 February 2021.