June 2018 marked the 150th anniversary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC). Working people in Reading started organising themselves to seek better pay and employment conditions from the mid-19th century.

Rural workers and friendly societies

In the early 19th century most working people in Berkshire were employed in agriculture. It was farming labourers who took the earliest action to improve their wages and protect their livelihoods against the increasing threat of mechanisation. The attempts of farm workers to build trade unions were often met by stiff resistance from employers and the authorities, as shown by the well-known story of the ‘Tolpuddle Martyrs’ in Dorset.

This was no different in Berkshire. In 1831 a man from Kintbury called William Winterbourne was hanged at Reading for his involvement in a labourer’s revolt that sought better wages and conditions. Two other men from Kintbury were reprieved after a petition successfully attracted 15,000 signatures from Reading citizens. However they were still transported to Australia along with 25 other local men.

Trade unions often grew out of the ‘Friendly Societies’ - groups of craftsmen who came together in organised societies to support their fellow workers. For example in 1841 the Friendly Society of Iron Moulders had 22 members in Reading. The branch gave assistance to men as they travelled around the country in search of work – known as ‘tramping’ – helping 275 ‘tramps’ that passed through the town in 1841.

By the late 19th century there was an impetus to develop general trade unions. In 1893 the Berkshire Agricultural and General Workers Union was formed, organised by Lorenzo Quelch, a prominent figure in the local labour movement. This unity between town and country also avoided farm workers being used as blackleg labour to defeat strikes by urban employers.

Huntley & Palmers 'Wheat Harvest in England' trade card, 1903 (museum no. 1997.82.204g)

Reading - Urban industry and poverty

In Reading itself increasing industrialisation had led to the town’s rapid growth but many workers faced low-pay, poor working and inadequate housing. Many workers were moving from the countryside into the town to find work.

Lorenzo Quelch’s own life mirrors this trend. He started work aged 8 as a cattle drover in Hungerford, later becoming a foundry worker in Newbury and then Reading. His involvement in the labour movement was dominated by his dealings with Reading’s largest employer Huntley & Palmers biscuit factory which by 1900 employed over 5000 people and was the world’s biggest biscuit factory.

By the 1900s Huntley & Palmers employed up to 25% of Reading’s working population. Although fondly remembered by many as a paternalistic employer this was found to be having a real impact people’s lives. A 1912 survey by University College Reading (the forerunner of the University of Reading) found that 20% of all Reading families were living in poverty below the level needed to maintain physical health by the standards of the day. This was primarily due to the suppression of wages caused by the company’s stranglehold on the labour market; hence Quelch called Huntley & Palmers ‘that hydra-headed monster of capitalism’.

Coley Steps, Reading in 1911. This was one of Reading's worst areas of slum housing (detail of museum object no. 1999.1.1)

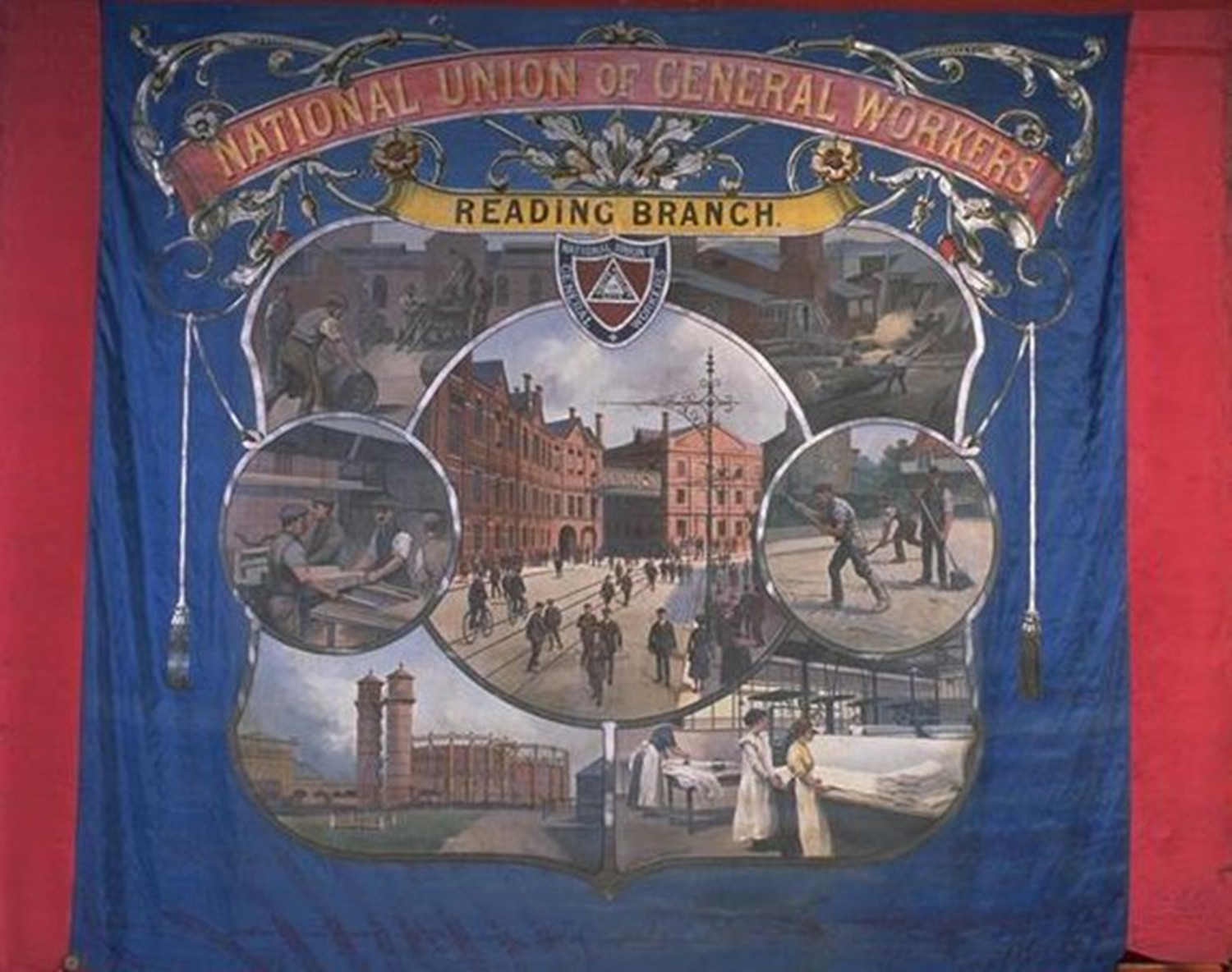

The reaction to this was the founding of the Reading Trades and Labour Council and a branch of the Social Democratic Federation, a Marxist party, both in 1891. It is no coincidence that the SDF’s national secretary was Harry Quelch, the brother of Lorenzo. Trade union membership in Reading expanded further with the establishment of a branch of the National Union of Gasworkers and General Workers (NUGGW) in 1911.

The majority of the NUGGW's members in Reading worked at Huntley & Palmers but general workers in other trades and industries could also join. The biscuit company ill-advisedly reacted to this development by laying-off 200 temporary workers and sacking some long serving employees. A leaflet was issued by the Reading Trades and Labour Council entitled ‘The Victimisation at Huntley & Palmers – a Fight for Life and Liberty’ and mass meetings followed.

National Union of Gasworkers and General Workers Reading Branch banner, 1919 (museum object no. 1997.154.1)

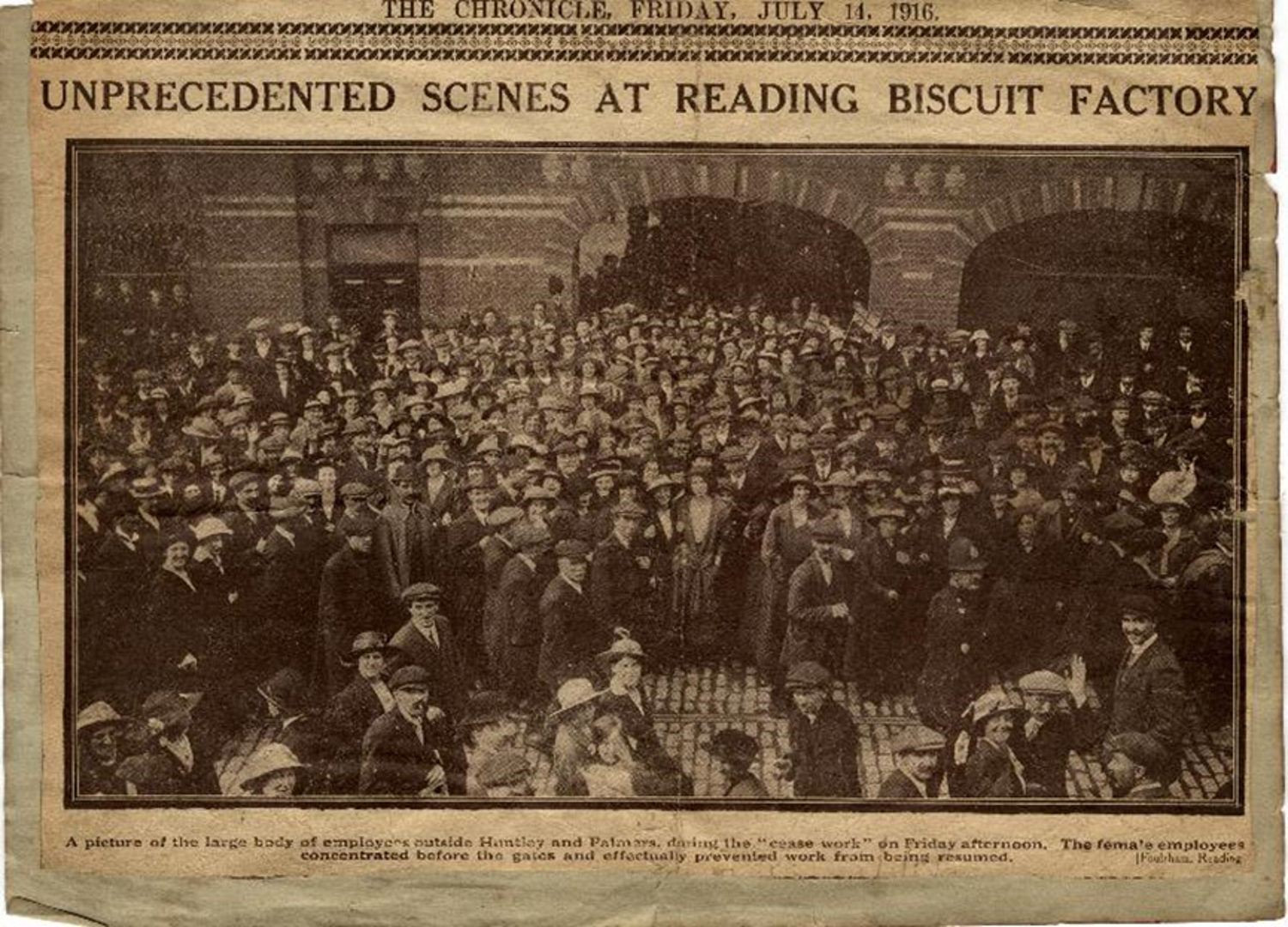

Industrial unrest at the biscuit factory

In July 1916 labour relations worsened after a girl was sacked for leaving work early without permission. Fifteen other girls who protested against her dismissal were also sacked. The NUGGW passed resolutions demanding higher pay and better working conditions. An increase of 5 shillings for men and 3 shillings for women was offered with the abolition of the war bonus. The union demanded this increase on top of the bonus, and called a strike from midday on Friday 14 July. However, after a meeting with Howard Palmer, the union accepted the offer and the strike ended. Soon after the company decided to create a Workers Representation Committee which lead to far better industrial relations within the company.

Berkshire Chronicle cutting shows striking workers outside the biscuit factory entrance on King's Road, Reading, 14 July 1916 (museum no. 1973.705.1)

After the First World War - General Strike and worker welfare

After the First World War many workers were joining unions to protect their interests in uncertain times. Trade union membership reached around six and a half million by 1920. In 1920s Reading was relatively prosperous in contrast to a backdrop of insecurity nationally. The General Strike of 1926 lasted nine days. It was called throughout the United Kingdom in support of mine workers, who were fighting a drastic wage cut. Reading was not greatly affected by the strike, but it did prevent the Prince of Wales from opening the new Caversham Bridge in May 1926.

The labour movement was also working to improve people’s lives outside the workplace. Reading unions set up the first branch of the Workers Educational Association (WEA) just after the turn of the 20th century. While the Co-operative movement also became well established in Reading, growing from a single shop on the Caversham Road in 1860 to include a diary, bakery, jam factory and printing works by the mid-20th century. There were also social activities particularly focused on the Trade Union Club that opening in 1914 on the Oxford Road, before moving to larger premises in Minster Street in 1924 where it remained until 1989.

TUC club mug 1924 (museum object no. 2016.34.1)

Sources

Keith Jerome, January 1981, Exhibition leaflet for A Fight for Life and Liberty – A History of Reading Trades Council, Reading Museum 7 February to 14 March 1981

T.A.B Corley, 1972, Quaker Enterprise in Biscuits, Huntley & Palmers of Reading 1822-1972, Hutchinson (useful section on poverty, wages and trade disputes - references the 1912 Reading University College survey carried out by statistician A.L. Bowley - see A.L. Bowley and A.R. Burnett-Hurst, 1915, Livelihood and Poverty)

Peter Southerton, 1993, Reading Gaol by Reading Town, Berkshire Books