Deeds not words – the votes for women movement in and around Reading

100 years ago Reading citizens played an active role in the fight to extend the vote and democracy in the UK. February 2018 is 100 years since the Representation of the People Act gave all men over 21 and women over 30 the vote.

Our story begins more than a century ago

Between 1886 and 1911 women’s suffrage bills were repeatedly introduced and defeated.

The suffragettes were active across the country, holding meetings and demonstrations to publicise their demand of ‘votes for women’. These events were a shock to the society of the time. It was not thought to be proper for a woman to speak in public, let alone to participate in an outdoor demonstration! Members of this movement were nicknamed ‘suffragettes’ because they fought for women’s suffrage; meaning the right for women to vote.

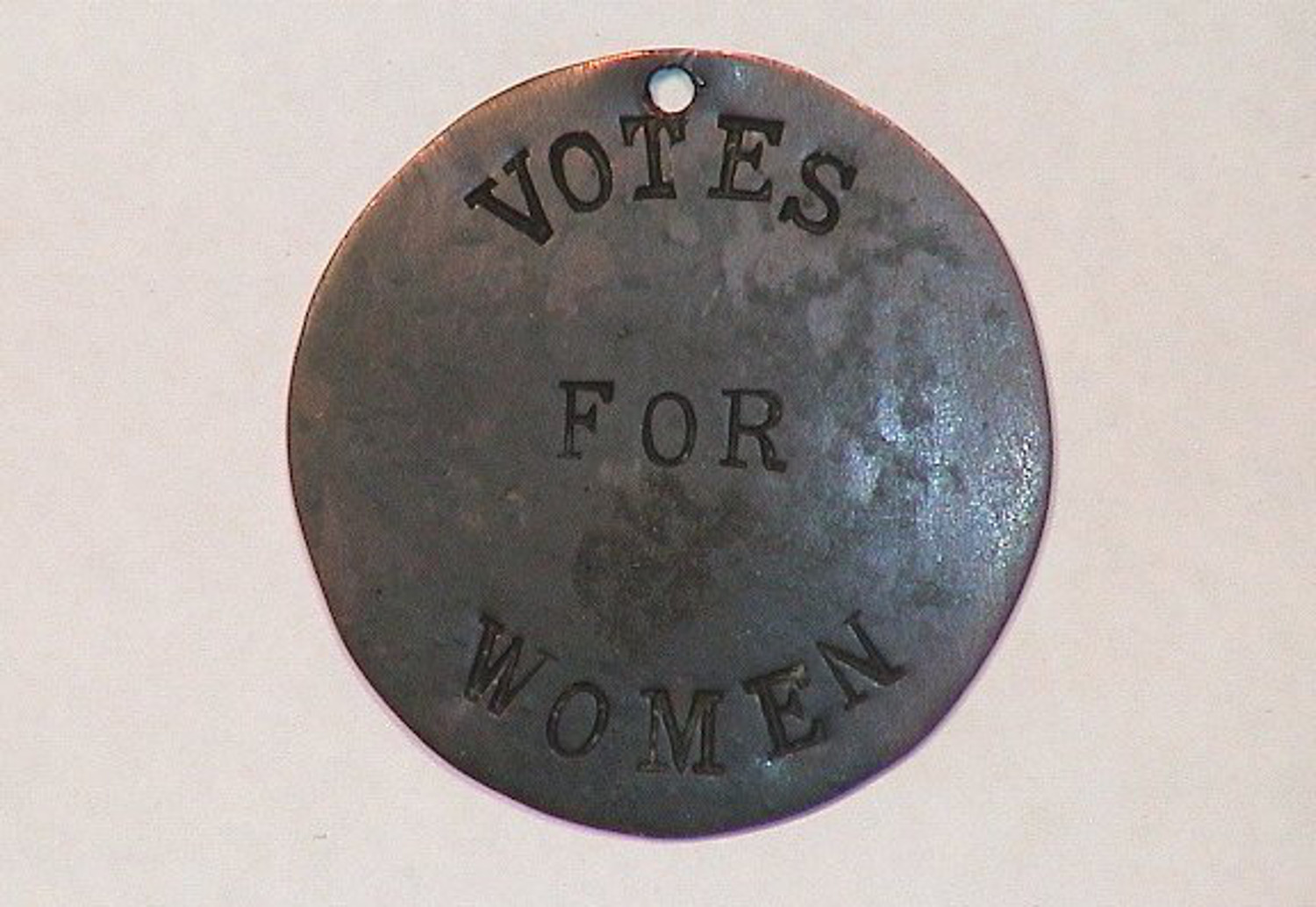

Women's Social and Political Union badge, 1900s (Museum object no. 1997.2.98)

Mrs Pankhurst and the WSPU

In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The WSPU employed many tactics to pressurise the government to extend the voting franchise to include women. For example in October 1906 Lord Haldane, then Secretary of State for War had visited University College, Reading to open the new hall and buildings. He only consented to come on condition that no woman, whether staff or student, was present at the ceremony.

Edith Sutton - local government pioneer

Reading had an active suffrage movement in the years before the outbreak of the First World War. Edith Sutton (of the Sutton’s Seeds family) had sought to persuade Reading’s local council to consider the issue for votes for women in 1904. Edith was one of the first five women to be elected to Borough and County Councils in 1907, after the Qualification of Women (County and Borough Councils) Act gave widows and unmarried women the right to stand anywhere in local government. She eventually joined the Labour Party in 1921 and was the first female Mayor of Reading.

Lively exchanges were recorded at many political meetings like the one held in favour of women’s suffrage at the Small Town Hall on 26 November 1907. At this meeting a large crowd of men were refused admittance to the hall by the police, though a fairly strong contingent managed to get inside. The unsympathetic males fired their first volley as soon as the speakers mounted the platform. It was recorded by local newspapers that a hurricane of squeals, whistling and cheering rented the air, the effect being enhanced by the introduction of tin horns and cries of ‘’Silence’’ from those who were making most of the noise! The meeting concluded when Councillor Edith Sutton rose to propose a vote of thanks to the speakers, and was received with loud cheers, and a voice said ‘’Aren’t you going to scatter seeds of kindness?’’ The meeting broke up without the formality of a reply to the vote of thanks.

In June 1908 some seventy members of the Reading Women’s Suffrage Society travelled to London by train to take part in a great procession organised by the various women’s suffrage societies. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies took the leading part in the organisation, which was confined to the less militant suffragist societies. Some fifty or sixty marched behind the Reading banner, which was one of the largest, and evoked many expressions of admiration from the crowd, coupled with enquiries for biscuits! The Reading contingent included some twelve or fourteen working women, including teachers and nurses. The lady doctors who went up with the members of the Reading Society joined the medical section, and one member marched with the Primrose League contingent.

Edith Mary Sutton, Mayor of Reading 1933-1934. Reading's first female mayor.

Edith Morley - higher education pioneer

Morley (1875-1964) was a lecturer in English Literature and Language at the University College, Reading (later the University of Reading), where she became the first woman professor at any English university. She was a Fabian socialist, and an enthusiastic suffragette in the Reading branch of the WSPU. Her position meant she took a prominent place in mass marches and meetings and even had her goods seized and sold because of her refusal to pay taxes. On one occasion, Morley was refused admittance to the Reading railway station on the way to London. Her protest was met by the answer that Herbert Asquith (Liberal Prime Minister from 1908-1916) was expected by the next train and that until his safe departure from the railway, no known suffragette - Morley was wearing her WSPU badge - could be admitted. In 1912 Morley urged Wilfred Owen, who was then living at Dundsen, to sit for a scholarship at the University College, and invited him to attend her remaining classes in Old English free of charge.

Miss Streatfield, Miss Hudson and Lloyd George

On 1 January 1910 David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, was making a speech at the tram sheds on Mill Lane, alongside Reading’s MP Rufus Isaacs.

Despite precautions, two suffragettes, Miss Streatfield and Miss Hudson, succeeded in getting into a meeting, but were discovered and ejected from the tram sheds. As Lloyd George was making a reference to robbery, one of the suffragettes shouted ‘You’re a robber, because you take the women’s money and don’t give them the vote.’ As Lloyd George left the meeting a man seized him by the collar and refused to let him pass. After the intervention of Rufus Isaacs a note was given to one of the newspaper representatives by the Chancellor’s assailant, which said ‘Don’t you think you’re a miserable hypocrite to reject as you do the just claim of women for enfranchisement? The great year when people fulfilled their right to self-government. B.A.H.’.

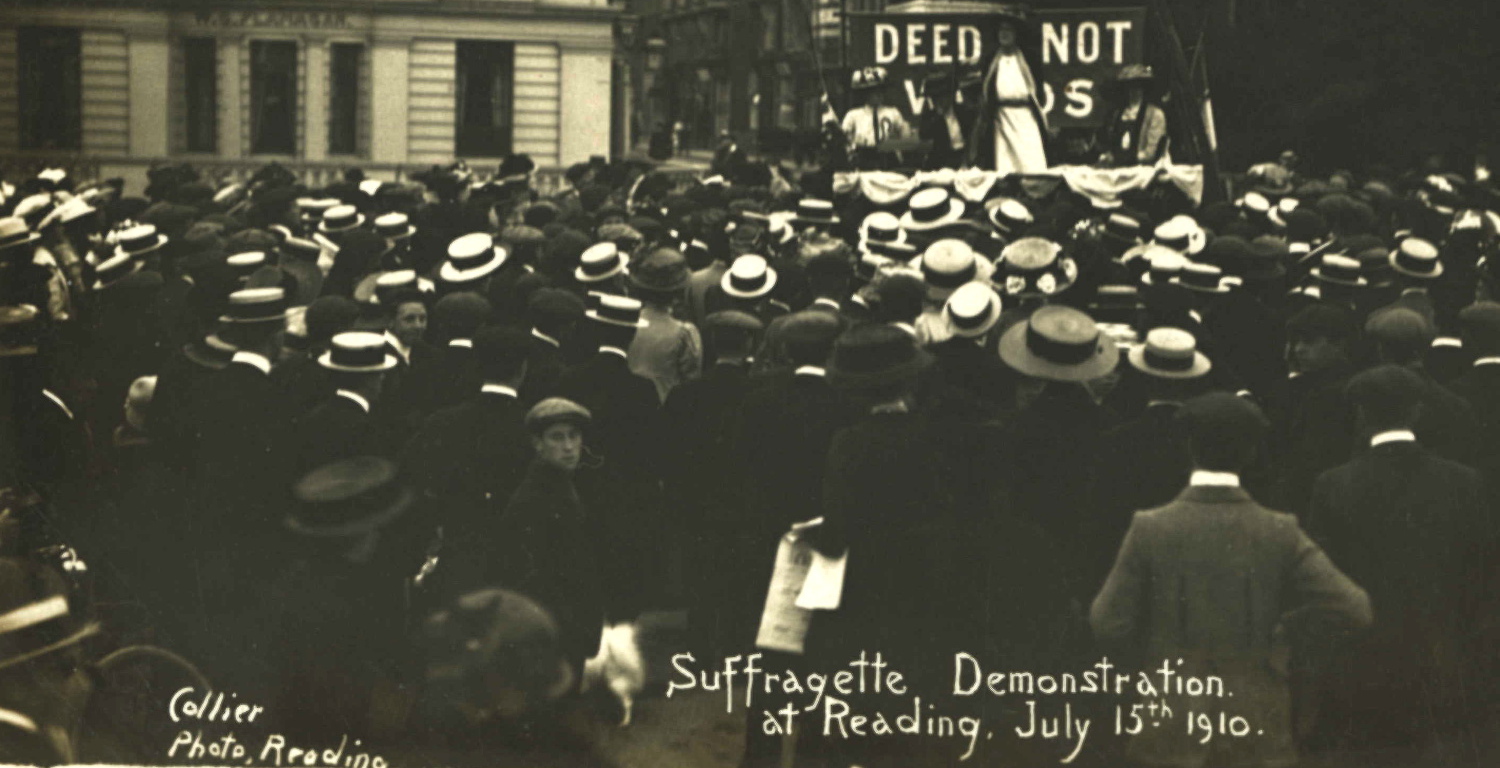

WSPU demo around the statue of King Edward VII in front of the Great Western Hotel, 1910 (Museum object no 1986.83.13)

Reading Demos

Later that year, on 15 July 1910 a suffragette demonstration took place on Station Road, Reading, around the statue of King Edward VII in front of the Great Western Hotel. The statue was used as the podium from which the suffragettes spoke, and to display a banner of the WSPU’s slogan, ‘Deeds not Words’. This slogan echoes the belief of the WSPU, that it was time for women to stand up and fight for the right to vote. The large crowd listening to the speakers shows the level of interest there was in the controversial demands of the WSPU.

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the militant suffragists, had made a speech at a meeting of the WSPU at Reading Town Hall on 18 November 1910. The local press reported that she had clearly indicated there would be a ‘raid’ on the House of Commons by women suffragists. She had said that a deputation of women would go to ask the Prime Minister why he set the majority of his own House at defiance, and why he refused to put his own Liberal principles into practice. She said that the time for making speeches and carrying resolutions was past, and that the time for action had arrived.

Mabel Norton of Caversham

Suffragettes were increasingly radical, rebellious and prepared to take militant action. Mabel Norton, of Caversham, a member of the Reading branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union, which had a premises in West Street, Reading, was sentenced to seven days’ at Holloway prison for her part in a demonstration. She was reported as giving a ‘racy account’ of her experiences at a meeting of sympathisers on the 14 December 1911. Norton described how ‘I wasn't a bit hysterical when I took a small hammer and smashed five windows one after the other. I did it quietly and deliberately. Then a walk down the street to the police-station cheered by a friendly crowd.’

Another local militant suffragette was Jessie Laws of Lower Armour Road in Tilehurst. She was arrested more than once (including for a raid on the House of Commons in June 1909 along with their first cousin Emmaline Pethick-Lawrence, treasurer of the WSPU). Her sister Henrietta Laws was a keen amateur artist and archaeologists with links with Reading Museum and the University of Reading.

Reading’s Rufus Isaacs was Lord Chief Justice and at the centre of national politics. Photo by Walton Adams of Reading (Reading Museum Object No 2016.10.23)

Reading's MP Rufus Isaacs

With increasing levels of direct action no government minister felt safe from suffragette interruptions. Reading’s Liberal MP, Rufus Isaacs, as the Attorney General was a member of the cabinet from 1912 (and only the second Jewish member of a British cabinet). His biography (written by his son) states that ‘Sir Rufus had himself always been in favour of granting them [women] the vote, and had gone so far to say that he saw no reason why a women should not be Lord Chancellor if she were the best qualified candidate for the office’.

As Attorney General, Isaacs was in fact responsible for overseeing the prosecution of key members of the militant suffragette movement for conspiracy to commit damage and injury, including Mrs Pankhurst. Isaacs was also implicated in the official policy of the forcible feeding of suffragette hunger-strikers and the iniquities of the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ which allowed hunger-strikers out of prison and then sanctioned their rearrest once they had recovered from the effects of their protest. Rufus Isaacs was quite clearly troubled by these developments.

By 1912 Isaac like all cabinet ministers was soon accompanied everywhere by detectives to protect him from sudden attacks, as some of the suffragettes’ deeds became more. Suffragettes became frustrated at the failure of peaceful protests to meet their demands, and began to employ more militant tactics. An incident in Wargrave, not far from Isaac's Reading constituency, showed this increased militancy.

Wargrave parish church was rebuilt in 1914-16 after it was damaged by fire

Wargrave Church fire

Along with the question of the rising tensions in Ireland and in Europe local newspapers throughout the summer of 1914 were dominated with stories of direct action by suffragettes. Arson had become one of their common methods of protest, a way to demonstrate their defiance to the government’s suppression of women. In the early hours of 1 June 1914 Wargrave parish church was set on fire and suffragettes were thought to be responsible. As a result of the fire the roof caved in, the bells fell from their tower and no glass was left in the windows.

Two women had been seen near the church the previous evening. Then at the scene of the fire some postcards were discovered on which were written pro-suffragette messages. These included ‘To the Government Hirelings and Women Torturers…a sample of the Governments boasted suppression of Militancy – Defiance!!!’

Concerned Curators

Reading Museum was also greatly concerned about such incidents. In June 1914 Mr T.W. Colyer, the Superintendent of the Museum, in correspondence with Mr Wright, the curator of Colchester Museum, revealed that the Museum’s committee had allowed him to engage an additional gallery attendant to provide security.

He goes on to say that ‘we all realise that if the Suffragettes intend doing damage here, or anywhere else, they will do it; as it is done so deliberate and no attempt made to escape, for it is done for publicity and so extra attendants would not prevent it. We are more afraid for the art section than the Silchester, for the latter collection is in strong plate glass cases and someone always on the spot. We have always an attendant in the Art Gallery, but we have some valuable works there which could be slashed and damaged beyond repair within a few seconds'.

This part we occasionally close – viz – when damage has been done at other galleries and put a notice up “Closed for rearranging”. This “rearranging” has sometimes run on for a month. We take particular care that whatever is done, that nothing shall appear on the minutes of the Committee to advertise the fact.

- Mr T.W. Colyer, Reading Museum Superintendent

The Great War 1914-1918

Yet only a few months later following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the suffragettes suspended their actions and pledged to help the war effort. They saw allied victory a more likely route to suffrage – the only reason they suspended their actions for the duration (though there are shades of Suffragette militancy in the 1916 Huntley & Palmers equal pay strikes – where women damaged biscuit factory equipment and goods).

Representation of the People Act 1918

In 1918 women over 30 were granted the right to vote, as a result of their actions during the war years. It would be another decade until full suffrage was granted in 1928, when the vote was extended to all women over 21 adding 8 million to the UK electorate.

The First World War precipitated the eventual granting of universal suffrage but there is clear evidence that the old world order was under threat before then, in Reading, as elsewhere. There was a long tradition of liberalism and non-conformism in Reading that gave rise to the strong tradition of female politicians and thinkers in Reading. Women like Phoebe Cusden MBE (recently commemorated by a blue plaque on her Castle Street home) are part of that tradition, along with Thora Silverthorne, and Professor Edith Morley. Universal suffrage was part of a great swell of change - a shifting in the political landscape from old orders - the rise of working class movements and global political power struggles that would define the 20th century.

References

Bartley, P. (1998) Votes for Women 1860-1928, Hodder & Stoughton

Gray, R. and Griffiths, S. (1986) The Book of Wargrave: History and Reminiscences by the people of Wargrave, Wargrave Local History Society

The Marquess of Reading (1942) Rufus Isaacs – First Marquess of Reading by His Son, Huchinson and Co.

Berkshire Chronicle, November 30, 1907

Reading Standard, June 20, 1908, January 5, 1910, November 19, 1910, December 23, 1911, July 26,1913