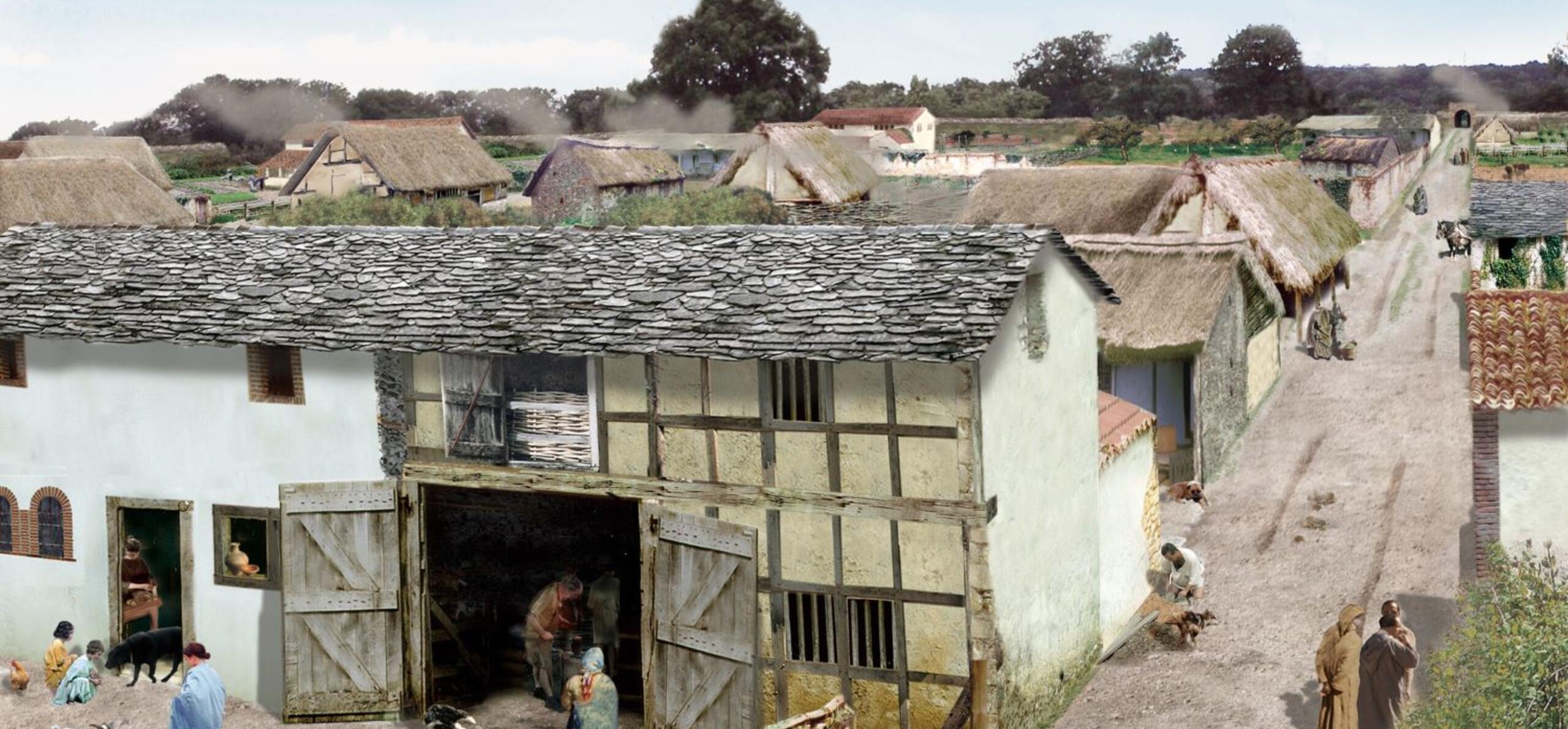

Professor Michael Fulford is Professor of Archaeology at the University of Reading. In this blog, he shares his latest research into human remains found in the settlement at Silchester and what this tells us about the ancient people of Silchester. It includes exclusive findings about a man with Spanish heritage in late Iron Age Britain.

This blog contains images of human skeletons.

As archaeological methods and sciences develop, we learn more and more about daily life and the collective actions of people in the ancient world. Yet, it still remains largely true that it is only through a person’s physical remains that we can begin to get an insight into an individual. In the case of Silchester, how can we approach the individual when its Iron Age and Roman cemeteries lie beyond the edges of the settlement and have yet to be explored? At the same time, how can we explain why some human remains have been discovered by antiquarian and modern excavators within the town when it was forbidden by Roman law to bury the dead within the settlement?

Human remains in the settlement

First, infants, where we should note that there was an exception regarding their burial. They are quite commonly found in Roman towns and settlements across the Empire and not just in Britain. As at Silchester, they are often found close to the hearth, in buildings or in their foundations and floors. The great majority of these died around birth and were buried in simple graves without any grave goods. Much more difficult to explain are finds of the remains of older people. These mostly occur as isolated finds of individual bones. They are not common, and there are also some rare instances of complete skeletons.

The reports of the early excavations give little or no clue as to the date of the contexts where remains were found, but, from one modern excavation, one complete skeleton of a young adult male was found in a rubbish pit beneath the forum basilica in the centre of the town and dating to around the time of the Roman Conquest (Fig. 1). His was a shallow grave, potentially vulnerable to scavenging dogs or foxes, and this may be one clue towards explaining the occurrence of isolated bones found elsewhere across the town. The repeated digging of foundations, wells and rubbish pits over the centuries can also account for the disturbance of burials and the scattering of an individual’s remains. But why were these individuals buried in the town in the first place, when the law forbade it?

Fig. 1. Young adult male (aged 25-30 years) found beneath the forum basilica, died around the time of the Roman Conquest.

Analysis of human remains

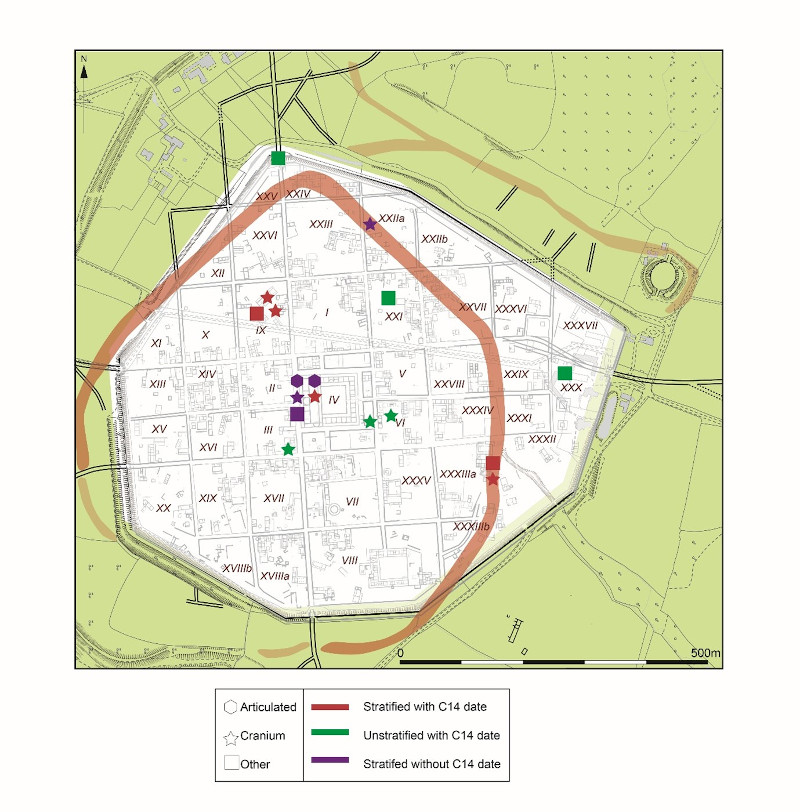

We have recently carried out a radiocarbon dating programme of the human remains from within the town (including samples from Reading Museum collections) and we found that they divide into an early and a late group, early around the time of the Roman Conquest, and late, in the fourth-to-early-fifth century, towards and around the end of the Roman town and the Roman occupation of Britain. Examples of the early group are found across the town with a slight concentration at the centre, while those in the late group are limited to the Roman North and West Gates and around the bath house (Figs. 2 and 4).

Fig. 2. The distribution of disarticulated latest Iron Age/earliest Roman human remains across the town with a concentration in the centre of the settlement.

Some of the early group have been found from very limited excavations in the ditch of the Iron Age defences. For example, deep beside what became the site of the Roman bath house were found the complete skull of a young adult male and part of the pelvis of an older female. The skull, already skeletonised and lacking its mandible, had been placed in the ditch on a wooden stretcher made of woven roundwood (Fig. 3). We can only guess where it was originally found, perhaps in the digging of the foundations of the first bath house, and perhaps with other parts of the skeleton, but then only the skull carefully re-buried, placed towards the bottom of the Iron Age ditch, but shortly after the Roman Conquest, as the pottery suggests a date around the mid-first century AD.

Fig. 3. The cranium of a young adult male (aged 25-30) from a mid-1st century fill towards the bottom of the Iron Age defensive ditch.

The skull was remarkably well preserved as was its DNA, the analysis of which produced remarkable results: the young man appeared to be of south-west European ancestry with close links to north Spain and the Basque region. However, further analyses suggested a different story. Strontium (87Sr/86Sr) and oxygen (δ18O) isotope analysis of enamel samples and sulfur (δ34S) isotope analysis of dentine collagen samples taken from teeth can tell us about where an individual lived as a child, in this case, approximately between 2.5 and 8 years of age. While the strontium isotopes in the enamel and sulfur isotopes in the dentine relate to the geology of where the person grew up, the oxygen isotopes reflect local water sources, providing information about climate and temperature. The results of the analyses are consistent with southern England, suggesting that he may have grown up in or very near Calleva (Silchester), meaning that the mother, but probably both parents, were in southern England, presumably at Calleva itself, when their son was born. We do not know exactly when he died but it would seem a time around the Roman invasion in AD 43 or 44 is very plausible. Caratacus, the Iron Age ruler who took the fight against the Roman invaders, was in control of Calleva at the time and the people whose remains have been found in the ditch could well have been victims of a Roman assault. This may also be the explanation of the early group of human bones, including the young man beneath the forum basilica whose ancient DNA, strontium and oxygen isotopes indicate his ancestry was similar to British Iron Age populations and that he could have lived locally. As the dating of some of the early group stands out as more probably late Iron Age, rather than Roman, we shouldn’t exclude the possibility of fatalities in conflicts between tribes before the Roman Conquest. This may explain a relative concentration of skull fragments around the centre of the Iron Age town.

If this man – possibly the son of parents from Spain - died in AD 44, the likely year for the Roman assault on Calleva, and was approximately 25-30 years old when he died, then it is possible he was born in the Iron Age town around AD 15-20. Here is the big mystery - what were people from northern Spain doing in Calleva at the beginning of the first century AD, when Verica was the ruler of the day? Were they traders? Archaeological finds at Calleva of fragmented vessels which carried olive oil, wine and fish sauce from Spain have been found in the Iron Age settlement. Or were they adventurers, he perhaps a mercenary recruited to support the local ruler? We can only speculate, but it is fascinating to think that the first people so far identified from northern Spain in Britain before the Roman Conquest should have had a life in the heart of Verica’s kingdom of the Atrebates, their son potentially resident at Calleva all his life. Both he and the young man found beneath the forum basilica would have lived through the power struggle when, if we believe the evidence of the Iron Age coins, Verica yielded control of Calleva to Epatticus, the brother of Cunobelin, the leader of the powerful tribe of the Catuvellauni with their centre at Camulodunum (Colchester), Essex. While Verica moved to a new centre close to the south coast at Chichester, our two individuals stayed put to live to see the Roman invasion.

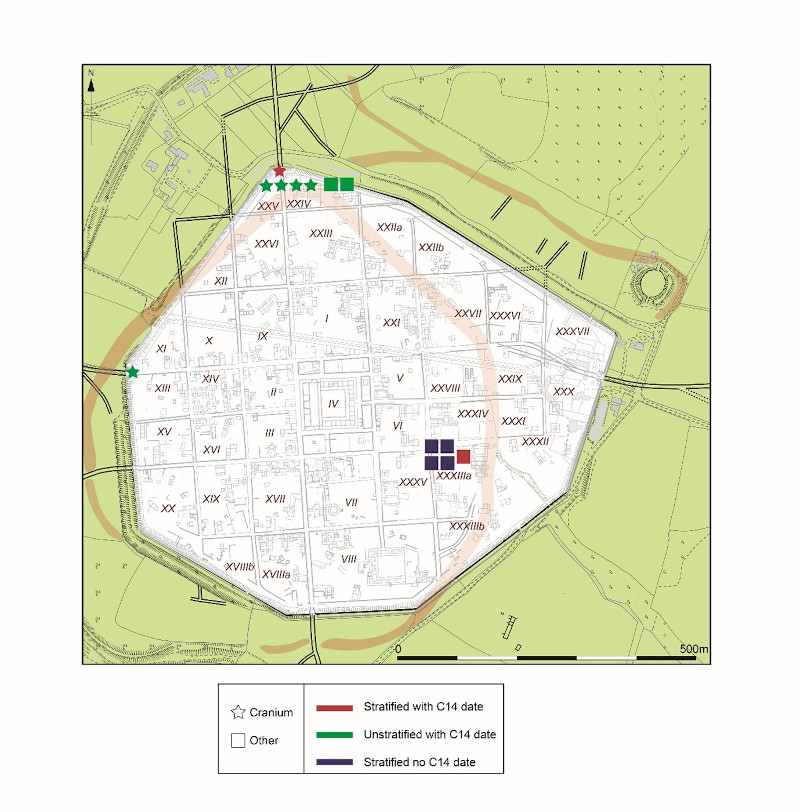

If our early scatter of human bones across the town might be the remains of victims of a Roman assault on Calleva in AD 43 or 44, individuals either buried in shallow graves or left unburied, our late Roman bones suggest a different story. The finds at the gates of the Roman town are predominantly of crania – skulls without mandibles – suggesting that heads had been deliberately displayed where they would be seen by people coming and going to the town (Fig. 4). Again, these could be the remains of people raiding the town or they could be the remains of judicial executions authorised by the town’s authorities. Decapitated burials, some of which are clearly the result of execution by sword or axe, occur widely in urban and rural cemeteries in the fourth and early fifth century, a sign perhaps of the breakdown of law and order in the Roman province. Other finds of human remains, as, for example, those around the bath house, also hint at a decline in urban authority.

Fig. 4. The distribution of disarticulated human remains in late Roman Silchester. Note the incidence of skulls at the West and North Gates.

Conclusion

To conclude, the scientific analysis of the skeletal remains from Silchester has given us much new information to enrich our knowledge of the Iron Age and Roman town. The evidence points to two episodes of violence when individuals were not buried outside the town in the way we would have expected, one dating to the time around the Roman conquest of southern Britain, the other to the later fourth century when Roman authority was beginning to break down in Britain. As to the individual, the presence of a man born in or near Calleva of northern Spanish parents points to the extraordinary reach of the Iron Age kingdom of Verica and the Atrebates. But the personalities and the life stories of the individuals we now know who grew up and lived in the town remain as elusive as ever.

Acknowledgements

I thank Reading Museum for permission to sample the human remains from Silchester and I thank Madeleine Ding, Professor Ian Armit and Dr Maddy Bleasdale at the University of York and Professor Derek Hamilton at the University of Glasgow for their helpful comments.