Reading Museum opened to the public in 1883. The collections acquired and displayed in its earliest days were intended to educate visitors about global civilisations and cultures, as well as interpret the history of the local area. This was before the invention of television, when museums were one of the few ways that local people could explore historic objects and visual depictions of the past. Today we focus on collecting linked with Reading, its people and environment, and celebrate our town and its fascinating history.

Collecting – Victorian and modern

The Bland Collection, brought together by Horatio Bland, formed most of the content in the museum’s first galleries in the 1880s. It was a collection of fascinating objects from around the world, from a duck-billed platypus to Ancient Greek pottery. Over time, these were added to by subsequent donors who gave high quality objects both from the ancient world and modern world cultures.

Reading Museum Gallery 1, 1903, packed with objects from hand axes to stuffed animals. Museum object number 1996.236.23

In the Victorian period, many British people including the wealthy, missionaries, soldiers, and government officials had increasing opportunities to travel abroad, not least within the colonies of the British Empire. On their journeys, some people collected and described as many specimens and artefacts from other countries as possible. Others filled their cabinets and shelves with pieces they regarded as ‘objects of curiosity’: some were acquired locally, and others came from distant parts of the globe. Objects like these formed part of Reading Museum’s founding collections.

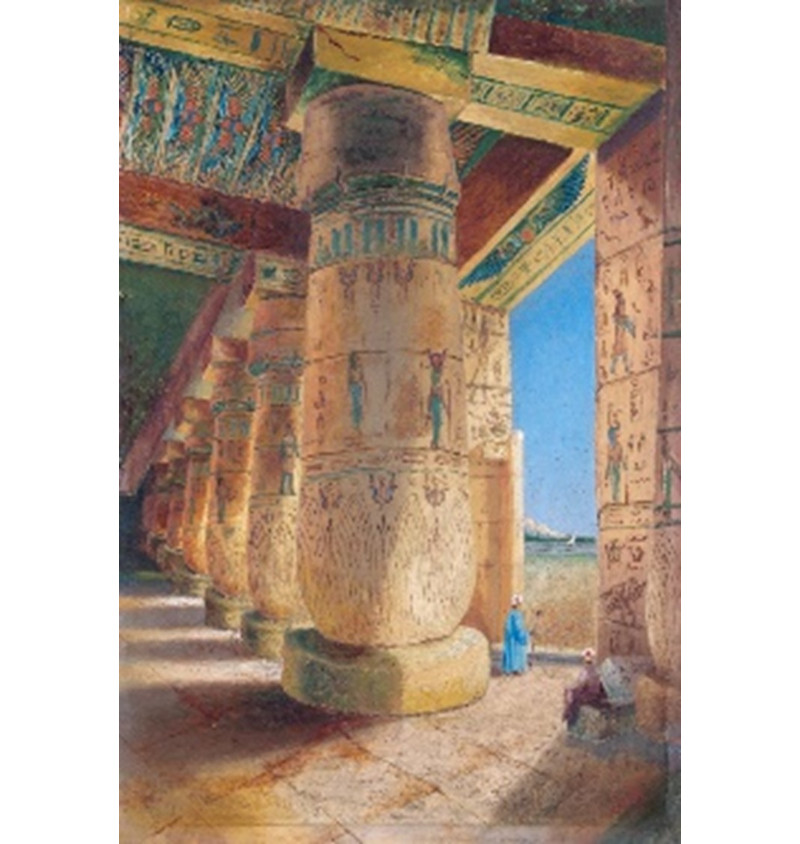

The Temple of Medinet Habu, oil on canvas, by Amelia Mary Ann Heelas (1843-1922). Amelia’s family owned Reading’s Heelas department store (now John Lewis), so she had the time and money to travel abroad. Museum object number REDMG: 1998.161.1

Today, our collecting criteria are radically different and are guided by a Collection Development Policy approved by our governing body. We very rarely acquire material from world cultures unless they have a strong link to Reading’s own diverse and multicultural population. We now focus on interpreting the history and environment of Reading, the surrounding area, and the lives and experiences of local people. In the Victorian era, Britain was at the centre of a global empire, and objects collected from around the world were placed in Britain’s museums. The ways in which those objects were collected continues to pose challenges to museums and curators today. In some circumstances it can lead to the return of objects to a country or people of origin (this is known as repatriation or restitution within our Collection Development Policy). This reappraisal of collections has grown in importance as museums involve more perspectives, cultures, and histories in the stories that we tell, that in turn changes how we understand the objects in our care.

In this blog, learn about the ancient history objects from outside Britain as well as Roman British finds in the collections at Reading Museum. Discover the stories of these objects, how they came to Reading Museum, and the ways in which the museum today engages with the collecting of the past.

Egyptian collection

The majority of the Egyptian collection at Reading Museum came from archaeological excavations that took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Reading Museum responded to appeals for financial support for excavations from both the Egypt Exploration Society and The British School of Archaeology in Egypt. With the permission of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, contributing museums received a percentage of the objects uncovered, based on the amount of money they had provided in financing excavation. The legacy of this system is that objects from the same season of excavations became dispersed across museums all over the world. This allocation of objects to funders outside Egypt would not happen today.

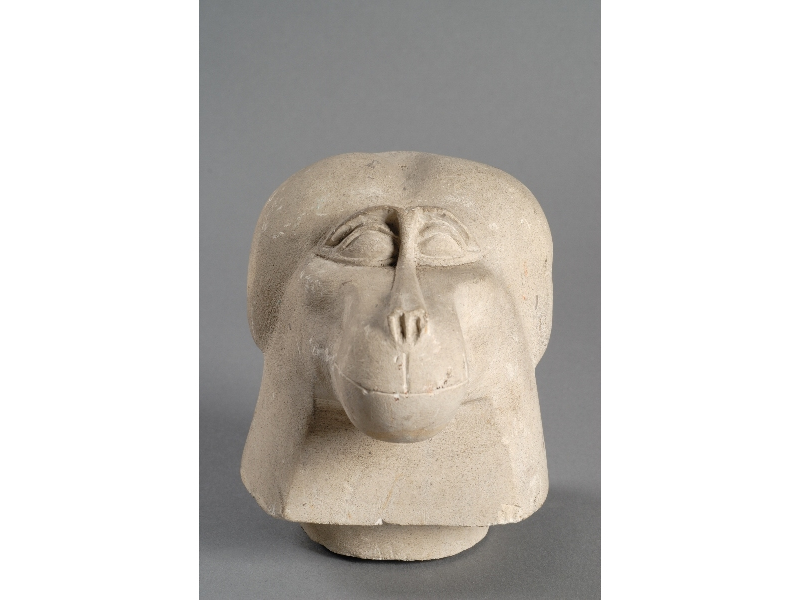

Limestone canopic jar lid in the form of a baboon’s head from Abydos, Museum object number REDMG : 1958.40.1. The baboon represents Hapy, one of the sons of Horus.

Other early donors to Reading Museum include British explorer and collector Heywood Walter Seton-Karr and local resident Henrietta Lawes. Henrietta Lawes (1861-1947) was an artist who grew up in Caversham and was one of the many people involved with the Egyptian Exploration Society. In 1899, she assisted with the donation of finds to Reading Museum from Flinders Petrie’s excavations at the burial site at Hu.

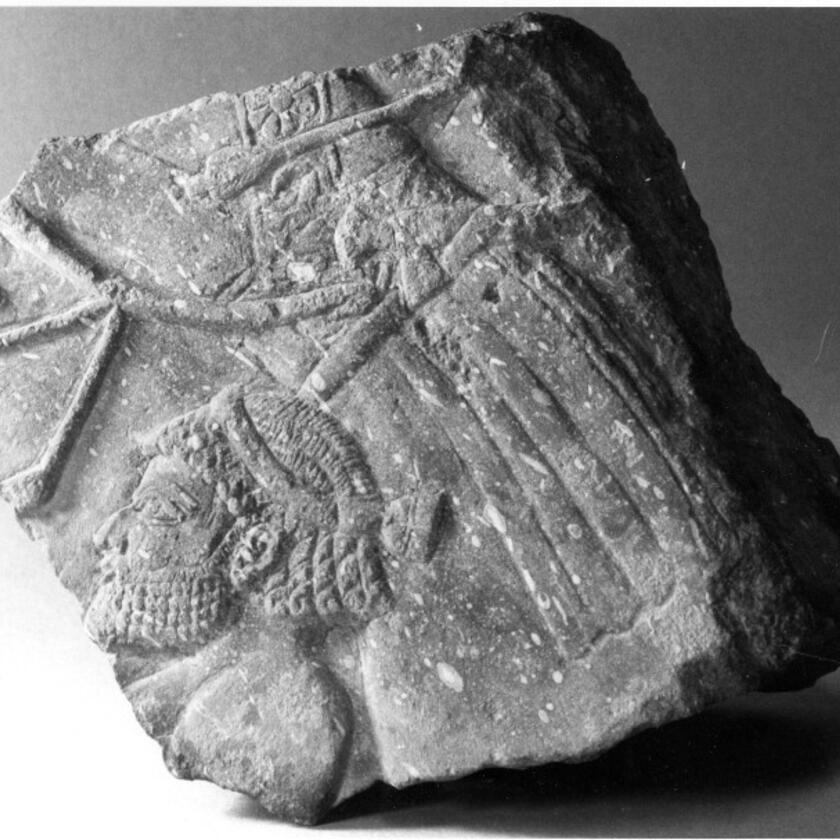

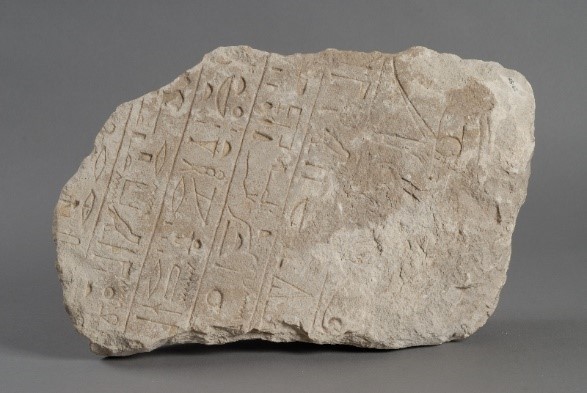

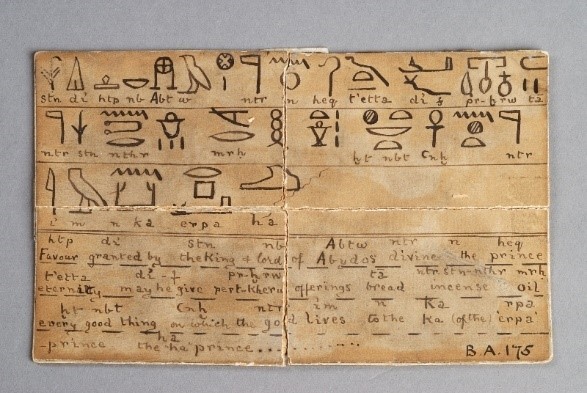

Upper part of a stela from Abydos, 12th Dynasty, Museum object number 1958.29.1. Donated to the museum by the Egyptian Exploration Fund in 1902.

The stela has an inscription in hieroglyphs dedicated to an unknown prince or governor, accompanied by a paper translation inscription of the hieroglyphs by Henrietta Lawes.

Objects in the collection span various periods of Ancient Egyptian civilisation, which lasted almost three millennia – from its unification around 3100 BC to its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BC, when ancient Egypt was the pre-eminent civilization in the Mediterranean world. Artefacts within the collection originate from various important sites across ancient Egypt, such as the Valley of the Kings, the Giza plateau, the temple of Karnak, Naqada, and Memphis, which was the oldest and most important city in ancient Egypt. They include early prehistoric flint tools, finely decorated pottery, jewellery, and sacred amulets made from precious gemstones, architectural fragments and statues decorated with hieroglyphic texts, mummy masks and mummified animals, as well as ancient Egyptian textiles.

Flint knife from Tarkhan cemetery, near Cairo, Museum object number REDMG : 1946.166.1.

This First Dynasty (3000-2890 BC) flint knife was discovered in grave 1982 in Tarkhan cemetery, south of modern-day Cairo. Other finds in the grave consisted of another flint knife, fragments of ten alabaster vases - one fragment bearing the name of King Narmer who was considered the unifier of Upper and Lower Egypt and founder of the First Dynasty of ancient Egypt.

Gilded funerary mummy mask, ancient Egypt, Museum object number REDMG : 1998.119.1.

This gilded funerary mask is made of cartonnage - layers of papyrus and plaster. It was put over the head of a mummy, representing the deceased in an ideal state for the afterlife. The mask also protected the head without which the dead person could not see, hear, eat, speak or breathe in the afterlife.

Like museums throughout the Europe, the Egyptian Collection at Reading Museum has enabled us to share ancient Egyptian history with our visitors over the last 100 years. Today modern academic research and digitisation enables us to share and reunite these collections with audiences wherever they are in the world.

Greek collection

Most of the objects in the Greek collection were given to Reading Museum by Lord Arthur Hill in 1899. He collected 270 objects of Greek and Roman material during his tour of Greece and Italy, mostly in Corinth with some from Rome. Wealthy private collectors Horatio Bland, Sir William Mount and Alderman Field also gave Greek material to the museum.

The collection consists mostly of pottery objects but there are also objects of worked stone and decorated wall plaster fragments. The Greek pottery came from collectors who chose the items for their intrinsic beauty rather than their archaeological significance. These superb pots make a valuable contribution to the study of Greek ceramics, artistically and stylistically. Example of all types of pottery vessels are represented, especially tableware; amphora (jar), kylix (cup), lekanis (bowl), lekythos (bottle), oinochoes (jug) and tarantines (plate) are among some of them.

Greek red figure Pseudopanathenaic amphora 340-320 BC, probably from Apulia, Greece. Museum object number REDMG : 1951.159.1.

Amphorae are two-handled storage jars that would have held oil, wine, milk, or grain. ‘Amphora’ was also the term for a unit of measure. They were occasionally used as grave markers or as vessels for funerary offerings or human remains. This amphora's findspot is not known but it is likely to have come from Southern Italy, probably in the region of Apulia.

Greek Apulian red figure fish plate, 330 BC, Museum object number REDMG : 1951.144.1.

This plate is decorated with pictures of the fish or seafood that it presumably would have held. But most of them have been found in funerary contexts, so it could be that the fish images possibly represented symbolic offerings for the dead. Or these plates could have been in popular use among the living, then placed in tombs for continued use in the afterlife.

Since 1951, Reading Museum's collection of Greek pottery has been on loan to the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology in the Department of Classics, University of Reading, where many are on display. All these objects give us a glimpse into the lives of the ancient Greeks, how they lived, what they ate, and what their beliefs may have been.

Roman collection

Unlike the ancient Egyptians or Greeks, Romans came and lived in the British Isles. During the Roman period (43-410 AD) the army set up administration centres, built infrastructure and placated the local tribal groups. Over time people from across the Roman empire settled in Britain and many local people adopted Roman ways.

There are over 30,000 objects associated with the Roman period in the Museum collection. Most come from the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum (modern day Silchester) located 10 miles south of Reading and are displayed in the Museum's Silchester Gallery. There is also material from sites in Berkshire and the middle Thames Valley, including what is now Reading. The finds come from excavations, archaeological surveys before building work takes place, objects dredged from rivers, surface finds and donations from local collectors.

Ceramic tile stamped with the name of Emperor Nero, produced by the tilers in Little London, Museum object number 1995.1.21.

This ceramic tile was stamped with the name of Emperor Nero, it was made at an imperial tilery at Little London near Pamber, not far from the Roman town of Calleva. Ceramic tiles were key Roman building material and pottery vessels were popular containers for cooking and storage, so pottery production was an important activity. The museum collection includes evidence of local pottery production from kiln sites at Swan Wood, Highmoor and from the 4th century Roman pottery kilns in Compton.

First Milman Road, Reading, hoard of coins. Museum object number 1948.15

A spectacular and valuable sign of the Roman presence in Reading are coin hoards found in the town. In 1895 two large coin hoards were found in the Milman Road area of Reading. In the February of 1895 a pot containing about 50 siliquae (silver coins) was found in a disused gravel pit on Bob's Mount. Frost caused a gravel fall revealing the hoard to boys sliding on the ice. Later that year in December while digging house foundations a pot of 120 Roman coins was discovered.

In 2015 a coin hoard was discovered during excavations at The Ridgeway School, Whitley in south Reading. The site revealed evidence of Bronze Age occupation and a Roman enclosure. The hoard contained 532 copper alloy radiates dating to the 3rd century AD. These coins were contemporary copies with an emperor wearing a radiate crown.

Roman bronze key from Battle Farm, Reading. Museum object number 1961.72.9.

This Roman key was found at Battle Farm in west Reading. Romans used door locks, padlocks and lockable storage boxes. This type of object was found along with pottery, animal bones, burnt flint, glass, leather, iron, tiles, etc. The variety of objects, along with architectural remains, tell us about the settlements, villas and enclosures of Roman time.

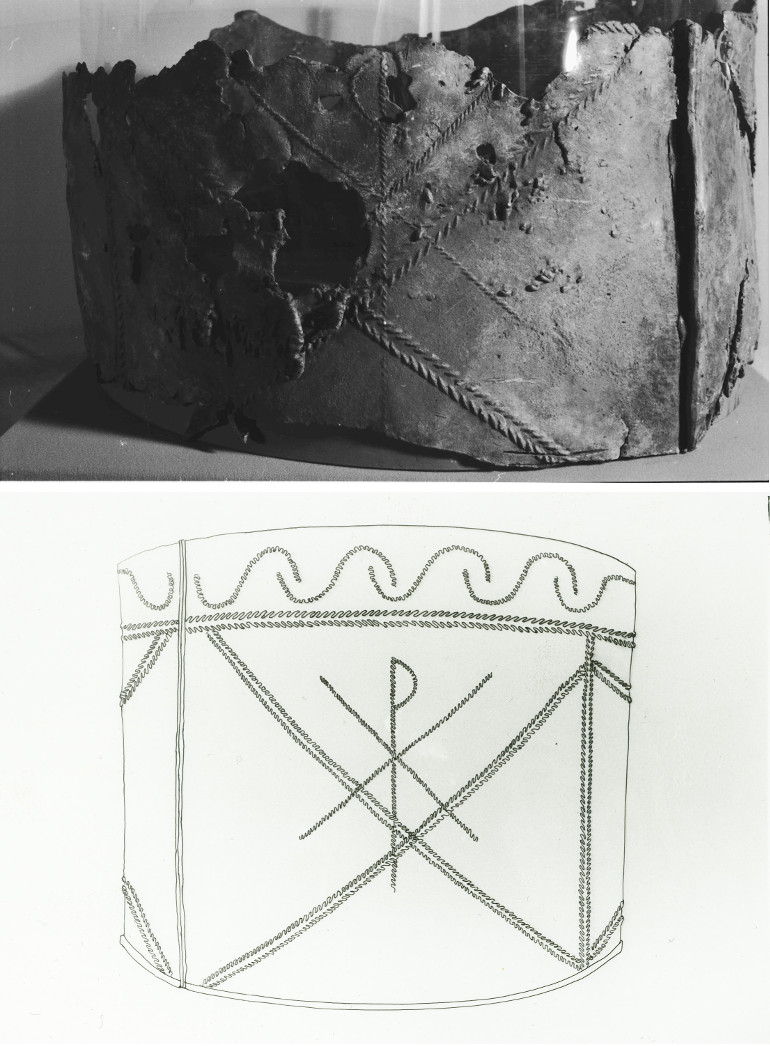

The Roman Caversham font. Top: font after conservation, bottom: reconstruction line drawing. Museum object number 1988.41.1.

A rare lead Christian font, more formally known as a 'liturgical tank', was discovered in the base of a Roman well during gravel-extraction at Dean's Farm, Caversham in April 1988. Dating from the 4th century AD the font is the earliest piece of evidence for Christianity in the middle Thames Valley.

Other ancient history objects

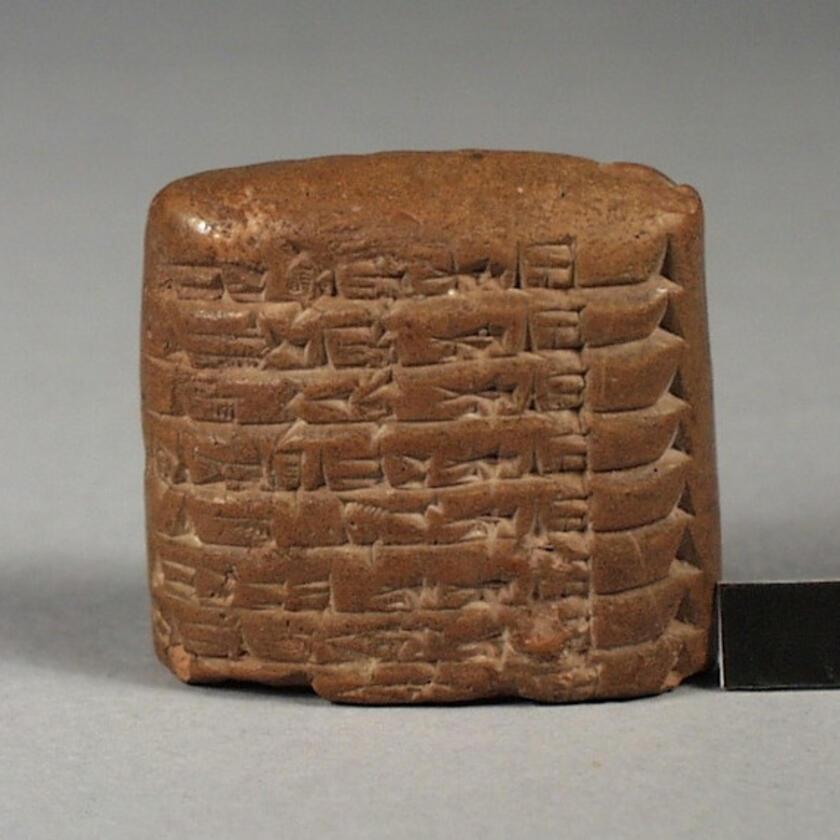

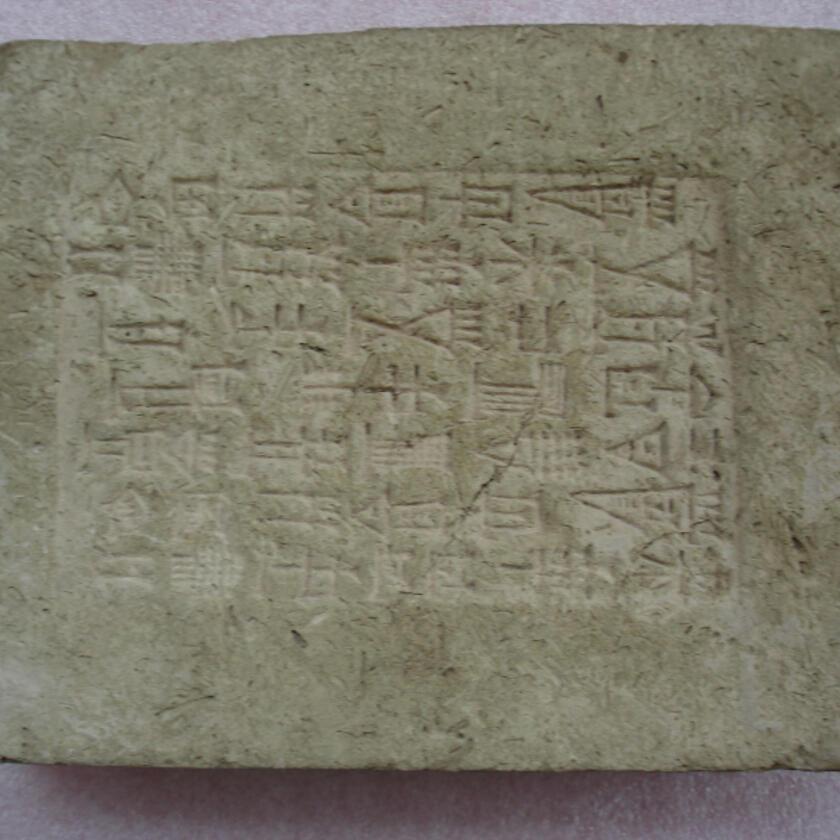

The museum has objects from various other ancient civilizations and cultures from all over the world, again these were historically collected during the early days of the museum. Babylonian and Assyrian objects as well as a collection of Silesian pottery dating to the Late Bronze Age form part of the ancient history collections.

You can find out more about these and other objects in the ancient history collections by visiting our Collections Online website, reading related blogs and by visiting the museum where you can see some of the ancient history objects on display.