Discover how animals were worshipped in ancient Egypt as gods and goddesses, their sacred meanings, and why these creatures were revered so highly by the Egyptian people.

Animals in ancient Egypt

Whether as deities, pets, symbols of fertility, or objects of fear, protection and luck, animals played a significant role in both royal and non-royal life in ancient Egypt, featuring heavily in everyday secular and religious activities.

Animals often had attractive qualities that the ancient Egyptians perhaps admired and wanted to emulate. These included strength, the ability to ward off predators, protective nature, nurturing characteristics and connections to rebirth. Therefore, displaying their deities in the forms of animals, with particular characteristics, demonstrated what they believed about each god or goddess's nature.

A whole host of animals played important roles. The most well-known of these is probably the cat, which has its domestic origins in ancient Egypt. Large cats such as cheetahs and lions were kept as exotic pets and were emblems of royalty. Other animals that were feared by ancient Egyptians, such as crocodiles and hippopotami, were revered and worshipped in order to protect them from their wrath. The crocodile was said to be the god of water and could act as a symbol of pharaonic power and strength, whereas the ibis was believed to be the patron of writing and scribes.

In this blog, we take a closer look at some of the most sacred animals of ancient Egypt.

Cat

Cats are depicted in tomb scenes as early as the Old Kingdom (over 4600 years ago) and it is in this context that we first see their domestication. Some tomb scenes show cats sitting below their owner’s chair, giving the sense that at some time they were seen as beloved family pets. In fact, mummified cats are sometimes found buried with, or close to, their owners. Cats were more than likely valued as a form of pest control – they were handy to have around where stores of food were concerned, particularly in homes, granaries and fields, keeping mice and rats at bay.

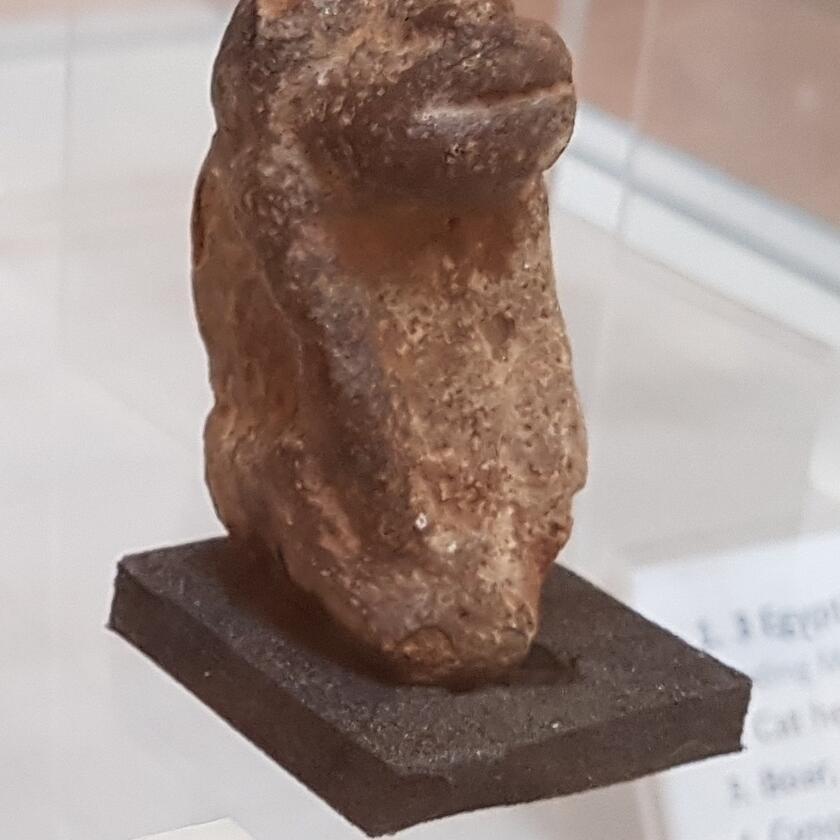

Romano-Egyptian seated wooden cat figure of Gayer-Anderson type (museum object number 1997.137.68). Currently on display in the ANIMAL: World Art Journeys exhibition.

Not only were cats highly regarded for their everyday uses, but also in the divine realm. The best known of the feline deities was Bastet, who was usually either depicted in the theriomorphic (animal) form of a cat, or the hybrid form of a female body with a cat’s head. Bastet was sometimes depicted as a lioness (in earlier times), or as a woman with the head of a lioness (however this was more often related to the goddess Sekhmet, associated with destruction). Bastet was seen as a more mild and calming version of the ferocious lion. She was most commonly identified as the ‘protector of children’, being associated with female fertility, sexuality, and the protection of infants and pregnant women.

The line between ancient Egyptian deities was often blurred - forms could overlap and some animals resulted in being associated with more than one god or goddess, and vice versa. Other goddesses sometimes took on feline forms, including Mut, Hathor and Tefnut. Although the association was predominantly female, there is one divine male cat often found within religious contexts, as a manifestation of the sun-god Ra. This tom-cat is depicted slaying the serpent god Apophis, who was an embodiment of chaos.

Copper-alloy head of a cat, representing the goddess Bastet, 26th Dynasty (museum object number 1951.11.1). Currently on display in the ANIMAL: World Art Journeys exhibition.

At the ‘Cemetery of Cats’ in Saqqara, northern Egypt, thousands of sacred cat mummies from the Late Period (c. 664–332 BC) were discovered. This was associated with a temple to Bastet. Ancient Egyptians would leave mummified animals (both real and fake) and statuettes as offerings to the cult of the god. These represented the species being offered to (in this instance, the cat), in an attempt to appease the god and seek their favour. Animals were also bred in large numbers specifically for performing these offerings. Interestingly, during the 19th century, cat mummies were exported on a mass scale to Europe, especially here in the United Kingdom, where they were used as fertiliser on the fields.

This Egyptian mummified cat was x-rayed by the Royal Berks Hospital and a video of the work made for a Meridian TV show in February 1997 (museum object number 2007.1101.1).

The domestic cat was not the only powerful feline in ancient Egypt – we also see the presence of big cats such as lions, leopards and cheetahs. Lions were often linked to royalty, as a symbol of kingship. Their grand appearance, strength and ferocity were surely qualities that the Pharaoh would want to emulate. Pharaohs were known to keep lions and other large cats as pets, perhaps not only as a status symbol, but also for their protective qualities, warding off ‘evil’. Lions are also shown being hunted in royal hunting scenes, as a display of the king’s strength to overcome even the most powerful of animals.

Our relationship with cats has certainly stood the test of time and their popularity is still evident today.

Dog

In Egyptian religion, there were a number of canine deities. Some of these were represented by the wolf or dog, while others like Anubis were more generic and exhibited qualities of both a dog and a jackal. Canine deities most often represent death and the afterlife, and are associated with the cult of Osiris (god of the underworld).

Before the rise of Osiris, Anubis was the most important funerary deity. He was the god of the dead, associated with embalming and mummification. He was the chief deity of the Cynopolis (Greek for ‘city of the dogs’), modern el-Qeis in Upper Egypt, and a burial ground for dogs was discovered on the opposite bank of the Nile.

Anubis was worshipped all over Egypt and images of the god were seen in temples, chapels and tombs throughout the pharaonic period. He is usually represented as a seated jackal or in human form with a jackal’s head, sometimes wearing a tail. The black colour of Anubis was symbolically associated with discoloration of the corpse after its preparation for burial and the fertile black soil of the Nile Valley, symbolising regeneration.

Faience amulet in the form of Anubis the jackal-headed god

Ibis

The sacred ibis was worshipped from Predynastic times (c. 5300-3000 BC) by the ancient Egyptians. The peak of cultic activities involving birds can be seen from the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty (c. 664-525 BC) to the Roman Period (c. 30 BC-AD 395), where sanctuaries dedicated to the worship of the ibis could be found throughout Egypt. Birds were raised both in captivity and found in the wild, and royal subsidies of fields allowed the cultic administration to feed the birds and raise capital by leasing land for cultivation. The species is now extinct throughout Egypt due to drainage of swamplands, their natural habitat.

In the ancient Egyptian language, an ibis on a perch was the hieroglyphic sign for the god Thoth. Thoth was the god of writing and knowledge and was frequently portrayed as an ibis-headed man. He was worshipped along with his little known consort Nehmentaway at the ancient city of Khumnw, near modern El-Ashmunein, on the west bank of the Nile. He is often referred to as ‘Lord of the Divine Words’ and recognised as the god of writing, scribes and wisdom. Believed to be the inventor of the art of writing and patron of all areas of knowledge, Thoth was responsible for all manner of accounts, records and written treaties as well as carer of libraries and scriptoria that were attached to temples. One of his most important roles was recording the ‘weighing of the heart’ ceremony.

Figure of a striding ibis from the Palace of Apries Memphis, Egypt (museum object number 1951.17.1). Currently on display in the ANIMAL: World Art Journeys exhibition

Thoth was frequently shown in ibis form or as a standing or seated ibis-headed man, usually holding a palette and pen or a notched palm leaf, engaging in some kind of administrative recording or calculation. It is possible that the long, curved beak of the ibis was identified with both the crescent moon and with the reed pen Thoth held. He was also associated with the moon (the 2nd eye of Ra’) when in baboon form (which we will cover later), wearing a lunar crown (a lunar disc or crescent). He appears on many temple walls assisting the gods or recording matters of importance relating to the king.

Figure of the god Thoth with an Ibis head and wearing wig and shendyt kilt (museum object number 1997.137.42).

In ancient Egypt, the mummification of sacred animals such as cats, dogs, crocodiles and ibises after death was big business. At Saqqara, the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital Memphis, more than 1.75 million ibis remains were discovered, with thousands more at the sacred city of Abydos and over 4 million in the catacombs of Tuna-el-Gebel, located in Al Minya Governorate in Middle Egypt.

Baboon

The baboon can be seen in imagery from as early as the Predynastic Period and it played a significant role in ancient Egyptian religion and cosmology. From the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2125 BC), human and monkey interaction was documented in wall paintings, where monkeys can be seen performing human activities and wearing leashes. Monkeys often appear as amulets, statuettes and as decorative elements on cosmetic articles. Young monkeys were also kept as pets in houses of wealthier individuals. However, the ancient Egyptians also recognised their wild, loud, aggressive and unpredictable side.

During the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1069 BC), monkeys were generally imported from south of Egypt (from Nubia and Punt), in order to be used in temples. They probably experienced a limited life expectancy due to their poor living conditions in the harsh desert environment, including insufficient food intake and a lack of movement and light. In later periods, sacred temple baboons were kept for ritual functions, mummified by the thousands and buried in coffins.

The baboon is probably most well-known as a manifestation of the moon god Thoth. In this role, Thoth took on the position as ‘god of the scribes’ (as mentioned previously), being associated with various subjects such as writing, science, judgement, knowledge and the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians probably recognised the human-like characteristics of the baboon, its intelligence and communication skills, and deemed it a suitable embodiment of this god. Thoth acted as a kind of mediator between the people and the gods. In iconography, baboon Thoth can often be seen in a squatting position with his hands on his knees and with a crescent moon or lunar disc atop his head. In scenes from the Book of the Dead, baboons are depicted guarding the ‘Lake of Fire’ whereby the dead could be redeemed, and sometimes, Thoth can be seen in his baboon form sitting on top of the judgement scales during the weighing of the heart, recording the decision. Therefore, Thoth could assist the dead in their passage to the hereafter.

Not only were baboons linked to the moon-god, but also to the cult of the sun-god. Baboons are known to greet the morning sun by barking – a theme often seen in ancient Egyptian art and sculpture, where baboons are depicted raising their hands to the sun in worship.

The baboon was also employed as a manifestation of the god Hapy, one of the Four Sons of Horus whose heads formed the lids of the canopic jars used to hold vital organs after death. The long-nosed, baboon-headed Hapy was intended to protect the mummified lungs in order for them to be restored to the deceased in the afterlife, and therefore be reborn. The lungs, liver, intestines and stomach were preserved during mummification and in the New Kingdom, these were placed into four canopic jars with the heads of the Four Sons of Horus (baboon, human, falcon and jackal). As time went on, the mummified organs would be placed back inside the body. Sometimes ‘dummy jars’ formed part of the burial equipment instead, so that the deceased could still receive the protection of the Four Sons of Horus.

Limestone canopic jar lid in the form of a baboon’s head from Abydos, Egypt (museum object number 1958.40.1). Currently on display in the ANIMAL: World Art Journeys exhibition.

Crocodile

The crocodile was one of Egypt’s most dangerous and feared animals. Consequently, it is no surprise that it came to hold an impressive degree of religious and mythological status to the ancient Egyptians, who sought to find ways to protect themselves from the wrath of such deadly creatures through their deification.

The crocodile god Sobek, whose name means simply ‘crocodile’, was a powerful deity worshipped from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman Period. The god’s sanctuaries were vast and widespread but the two main cult centres of Sobek were located in the ancient town of Shedet (Greek Crocodileopolis), in modern Medinet-el Faiyum in the Faiyum region and at the temple of Kom Ombo, in Upper Egypt (home to various Twelfth Dynasty rulers). Within the temples dedicated to Sobek it was usual to have pools full of sacred crocodiles, which were mummified after their death and placed in temples, tombs and burials.

He was a crocodile-headed god with several important connotations, including his association with the colour green. The worship of Sobek peaked in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055 -1650 BC), whose name is seen lent to several Twelfth and Thirteenth Dynasty Pharaohs such as Sobeknefru and Sobekhotep I –IV.

Flat silhouette of the god Sobek (or perhaps Hapi, son of Horus) in mummiform

In mythology, as written in the Pyramid texts, he is referred to as the ‘raging one’ who ‘takes women from their husbands whenever he wishes according to his desires’, but was also responsible for making green the grass in the fields and river banks, tying him to both procreativity and vegetative fertility. Most notably Sobek was the god of water and other areas where crocodiles were frequently found such as river banks and marshland, and it was believed that the River Nile arose from his sweat. He was linked to cults of other gods such as Osiris and Amun and in particular the sun god when in the form of Sobek-Ra, which lead to him being identified with Greek god of the sun Helios. Sobek was also closely associated with the king and could act as a symbol of pharaonic power and might.

He was represented as either a reptile itself, often seated upon a shrine or alter, or as a crocodile-headed man. In either form he usually wears a sun disc headdress with horns and tall plumes, and he may also wear a wig when in human form. Another crocodile-headed deity was Ammit, known as ‘devourer of the dead’. She was a crocodile-headed demoness and goddess with a body that was part hippopotamus and part lion, which were the three largest and most dangerous animals feared by ancient Egyptians. She can be most commonly seen in the weighing of the heart ceremony, waiting to devour impure hearts of the deceased, in doing so dooming their safe passage into the afterlife.

Hippopotamus

The hippopotamus was the largest animal indigenous to Egypt, but sadly, it has been completely extinct there since the early 19th century. From Prehistoric times, the hippo inhabited the River Nile. However, their relationship with the ancient Egyptians was somewhat hesitant – they were both admired and heavily feared. Being highly unpredictable, they were a danger to boats traveling along the river, as well as the people working along the riverbanks. Their sheer size (weighing up to 4 tons), sharp teeth, large jaw and speed makes them an extremely powerful mammal, and when feeling threatened they can become aggressive, particularly when protecting their young.

This sense of protectiveness over offspring is the main quality displayed by the most well-known of the hippopotamus-goddesses, Taweret (meaning ‘the great one’). Taweret was identified as the ‘protector of mothers and children’, in particular pregnant women and new born babies, being strongly associated with childbirth and fertility. She is most often shown standing upright on her hind legs, with the head and body of a hippo, the tail of a crocodile and the paws of a lioness, with a rounded pregnant belly and heavy breasts. Usually, she carries the symbol of protection. Her image (or more generally that of a hippo) often appears on household objects, magical ‘wands’, amulets and figurines. ‘Wands’ were usually carved from hippopotamus ivory, maintaining a curved shape. Taweret is often depicted on them, brandishing a knife, imbuing them with the power to ward off evil forces and provide a source of protection for the intended mother and child.

Green faience amulet of the hippopotamus goddess Taweret, from Hu in Egypt (museum object number 1997.137.41).

Hippopotami also appear in tomb scenes, where they are often being hunted in the marshes by the Pharaoh with a harpoon. This displayed the strength, power and bravery of the king, symbolising his ability to overcome chaotic forces and maintain Maat (world order). Hippos were hunted not only for food and their ivory, but also because of their destructive nature. Hippos have the ability to decimate fields of crops with their huge appetites, often grazing overnight – perhaps this explains the meaning of ‘hungry hippos’!

The hippo is also often found within grave goods, in the form of a blue faience model decorated with examples of river plants such as the lotus flower. This promotes a connection with growth, new life and cosmogony; rather than an image of chaos and ferocity. Hippos have the ability to continuously submerge themselves underwater for several minutes before resurfacing – a wonderful metaphor for rebirth and regeneration. When underwater, sometimes only their back is visible. This was reminiscent of the Egyptian creation myth where the first primeval mound rises up from the chaotic waters of Nun. The ancient Egyptians believed that placing hippopotamus models in their tombs would provide them with this renewing power and would guarantee their rebirth, by magically passing over these qualities. Interestingly, many hippo statues have been discovered with broken legs – it is possible that this was a deliberate attempt by the ancient people to avoid any unfortunate incidents with the animal after death, as it was believed that depictions in the tomb could magically come to life. For them, it was certainly better to be safe than sorry.

Today, hippos are regarded as the most deadly land animal in the world – it is easy to see why the ancient Egyptians felt so threatened by them and why they felt the need to placate them in any way that they could.

Scarab beetle

The sacred scarab beetle was modelled on the indigenous Egyptian dung beetle and is probably one of the most recognisable images from ancient Egypt. The insect spends its days rolling and crafting balls of dung, inside which the female beetle lays its eggs. The dung provides the larvae with not only a safe nest, but also a place for them to feed as they develop. The female beetle tends to the ball, eradicating mould and fungi, until the offspring surface as adults. A second ball is used for nourishment, sustaining the life of the beetle. This is rolled along the ground by the beetle’s hind legs and then deposited in an underground chamber. It is from this visual image that the idea was formed of the scarab beetle rolling the newly born morning sun disc across the sky, until it disappeared (or died) in the evening, only to be reborn again the next morning. Additionally, witnessing the emergence of new beetles from balls of dung would only further strengthen the connotations of scarab beetles with rebirth and regeneration. The ancient people seemed to believe that the dung beetle was spontaneously created in this way.

Finely detailed iridescent green scarab apparently on a copper base, possibly modern (museum object number 2003.89.1). Currently on display in the ANIMAL: World Art journeys exhibition.

The artistic depiction of the scarab was also used as a hieroglyphic symbol in its own right. The verb ‘to come into being’ was written with the sign of a scarab beetle. The noun ‘scarab’ literally translates as ‘that which comes into being’ or ‘manifestation’.

It was these metaphors that caused the scarab beetle to assume the embodiment of the god Khepri – the ‘god of the morning sun’ who could bring about his own birth. Khepri was often depicted as a male figure with a whole beetle set onto his shoulders. This took on a different form to other hybrid deities, who would only utilise the head of the animal on top a human body. Khepri was associated with creation and new life, as a subsidiary of the principal creator and sun-god, Ra.

Scarab beetles had several functions for the ancient Egyptians and came in various forms. Scarab amulets were probably the most common type, and replicas make rather popular souvenirs in Egypt and international museums today. They are mostly small and are usually pierced on either end, indicating that they were to be used in rings, necklaces and bracelets by the owner. They could be made from a variety of stones, the most recognisable probably being the blue faience scarabs which were popular in the New Kingdom. The underside could be inscribed with personal names, titles, kings’ names, protective sayings or drawings. This compact size meant large-scale distribution was much easier. A larger type of scarab amulet came in the form of the heart scarab. These were inscribed with a chapter from the Book of the Dead and were placed on top of the mummy or close to it. The function of the heart scarab was to prevent the heart of the deceased individual from speaking out against the owner during judgement in the underworld – this was crucial if the individual was to pass safely into the Kingdom of Osiris. It was thought that the heart scarab could control the memory and responsiveness of the dead. Large scarabs were also utilised by the royal family to make announcements – these were known as commemorative scarabs. Through this method, news of royal achievements could be spread among the population, as a kind of propaganda - there was no internet or television to do this for them!

Scarab beetles were clearly an important part of life and death, as a symbol of protection, creation and regeneration for the ancient Egyptians – certainly not the flesh-eating villains portrayed in popular culture!

The majority of the Egyptian artefacts in the Historic World Objects collections came from archaeological investigations of ancient Egyptian sites. Reading Museum responded to appeals for financial support for their excavations from both the Egypt Exploration Society and the British School of Archaeology in Egypt. With the permission of the Egyptian Antiquities Service contributing museums received many of the objects uncovered. The legacy of this system is that objects from the same season of excavation on the same site can be shared between many museums all over the world.

Animals of mystery and wonder

The ancient Egyptians worshipped a multitude of gods and goddesses, and an understanding of this is crucial to unlocking the secrets to Egyptian religion and mythology. Worship of the gods often involved people making regular offerings, accompanied by invocation, in order to ensure a continued and benign presence in their lives. Animals were mummified in the thousands in order to appease the gods and seek their favour. The object of worship was not the animals themselves, but the gods that took on their forms – animals acted as a kind of messenger between the people and the gods.

In this blog we have provided merely a taste of the many sacred animals that the ancient Egyptians worshipped, chosen due to their specific qualities and behaviours, and reflected in the deity that they epitomised. Utilising an animal’s head on top of a human body ensured that the gods could still interact with the world, at the same time as providing a visual metaphor through the animal’s characteristics.

Religion and mythology were central to the lives of the ancient Egyptians, and central to their religion were the deities they worshipped. The physical form of the deities allowed cultic or personal interaction with their gods, and whether it be in full animal form or a mix of animal and human, the ancient Egyptian sacred animals still to this day infuse a sense of mystery and wonder.

Find out more

Whatever your experience or background, there are lots of ways to explore all kinds of history at Reading Museum. Keep reading the Reading Museum blog, learn about our wide range of collections (including our complete replica Bayeux Tapestry), or explore our opportunities for schools (both online around the world and in-person).

Visiting the museum is free. All donations are enormously appreciated.