Reading, its Abbey and the Civil War

Simon Marsh, The Battlefields Trust

Today, it is difficult to imagine Reading in the midst of conflict. However, during the war between the King and Parliament from 1642 to 1646, our town was a place of enormous importance.

Reading sat astride both the Great West Road--which controlled the way to the west of the country--and the River Thames, a vital artery for the transport of military equipment and material from London to Parliament’s armies. Captured by the royalists in November 1642, the town became an important garrison after King Charles I had decided to make Oxford his war-time capital. For Parliament, the retaking of the town was necessary before operations against Oxford could be mounted.

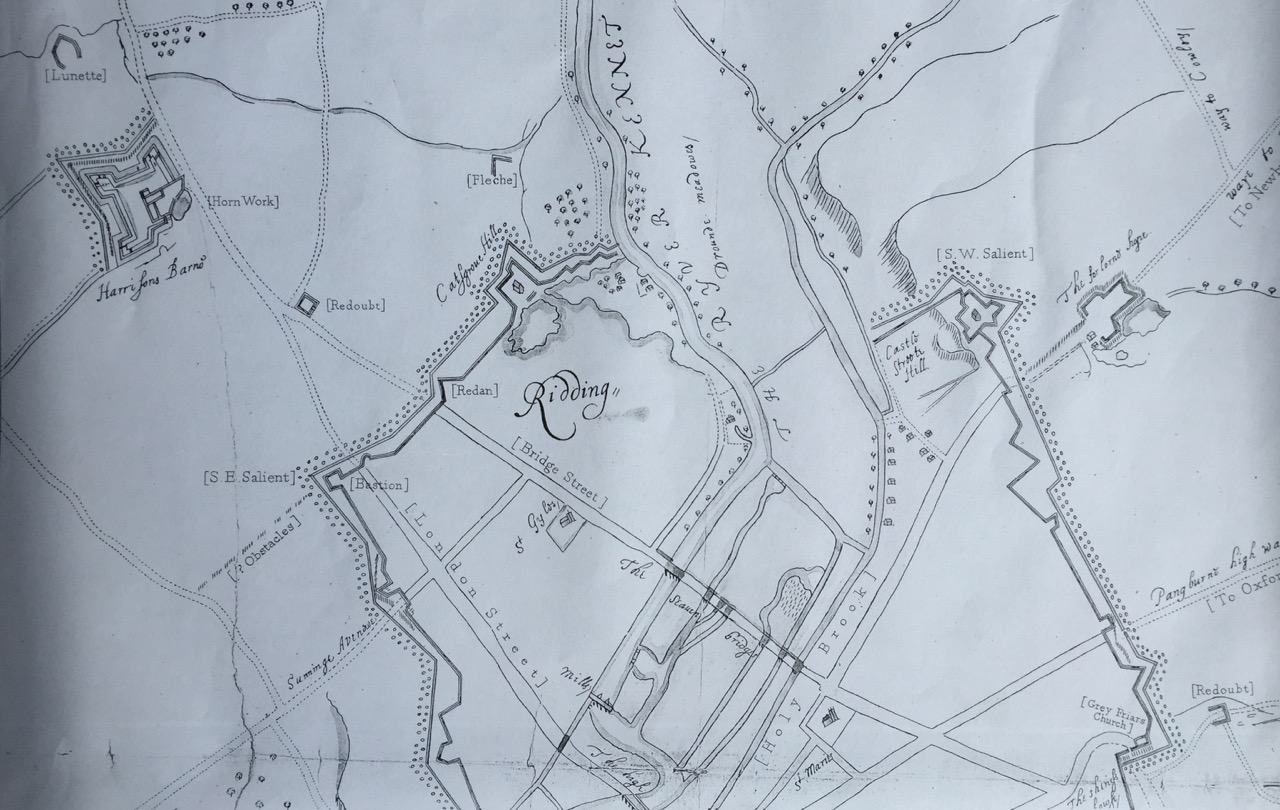

This series of events paved the way for one of the most important (but less well-known) acts in Reading’s history: the siege of April 1643. After taking the town, the Royalists had set about building earthworks to protect their garrison. This followed the seventeenth century practice of making a circuit of earthen walls around the town protected by bastions, with forts positioned outside the defensive line. Engineers designed these fortifications to protect against cannon fire and make assault dangerous and difficult. Below is a map of the defences, based on a copy of an original in the British Library (held by Berkshire Record Office). This likely depicts the 1643 defences as the fort at Forbury is not included.

Part of the defences of Reading in 1643

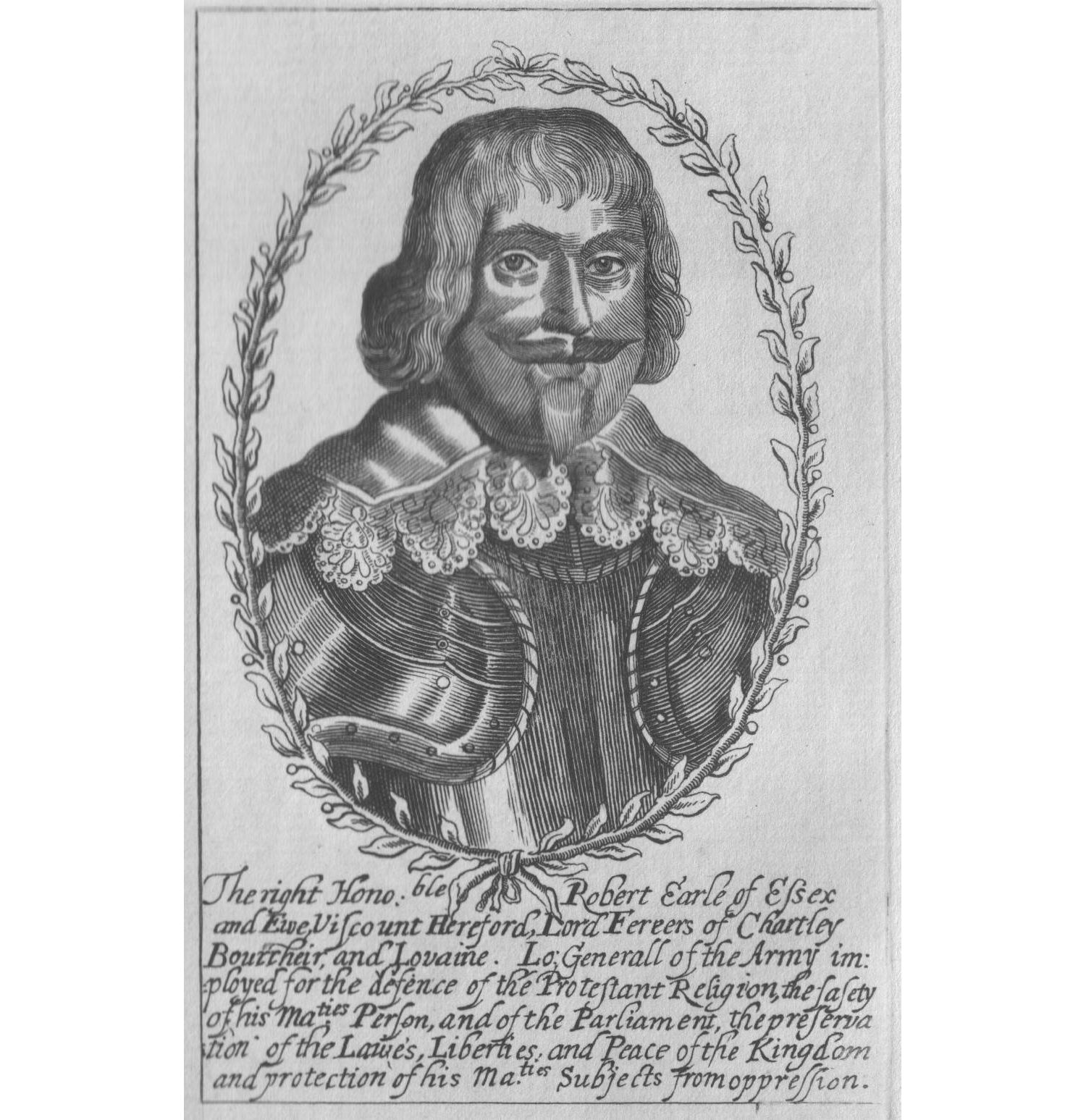

Parliament’s army under the command of the Earl of Essex left Windsor on 12 April 1643. It advanced south of Reading and swung around to the west of the town to begin the siege on 15 April. Essex made Southcote House his headquarters, began positioning his gun batteries and advancing trenches toward the town. The parliamentarians had more cannons than the defenders and maintained a higher rate of fire. When the royalists tried to mount a light gun in the steeple of St Giles’ church it was soon silenced by Essex’s cannon fire and a raid from the town to disrupt the siege lines was forced back.

The Earl of Essex

By 19 April the parliamentarians had advanced their guns within 400 metres of the town despite further attacks against them by the garrison. The royalist governor, Sir Arthur Aston was knocked unconscious by falling masonry dislodged by cannon fire and was replaced by Colonel Richard Feilding. On the same day Essex’s men were joined by more troops raised in the eastern counties of England and these occupied the area to the east of Reading, encircling the town.

By 21 April the parliamentarian trenches were within 50m of the town, but the royalists in Oxford had begun making efforts to relieve the garrison. Soldiers and barrels of gunpowder were barged into Reading overnight of 18 April and a further relief effort involving a force of cavalry was planned for 23 April. This failed, in part, because the messenger sent to swim the Thames to inform the garrison was captured and divulged the plan.

With gunpowder supplies low, Colonel Feilding decided to open surrender negotiations with the besiegers on 25 April. But the King had set out from Oxford with a relief force of 6,000 men which appeared on Caversham Hill that afternoon. They moved to attack the parliamentarian regiments which had been quickly sent across the Thames to prevent their advance. A battle soon developed with Essex’s men holding a barn and lining the hedgerows to prevent the royalist reaching the town. Feilding was urged to assault the parliamentarians by a messenger sent into Reading. But he refused as he had given his word not to attack whilst talking about surrender. More parliamentarians joined the battle and eventually the King was forced to withdraw. Surrender terms were agreed on 26 April and these allowed the garrison to march out the day after with:

flying colours, armes, four peeces of ordnance, with lighted matches and balls in their [soldiers’] mouth

- 26 April surrender terms

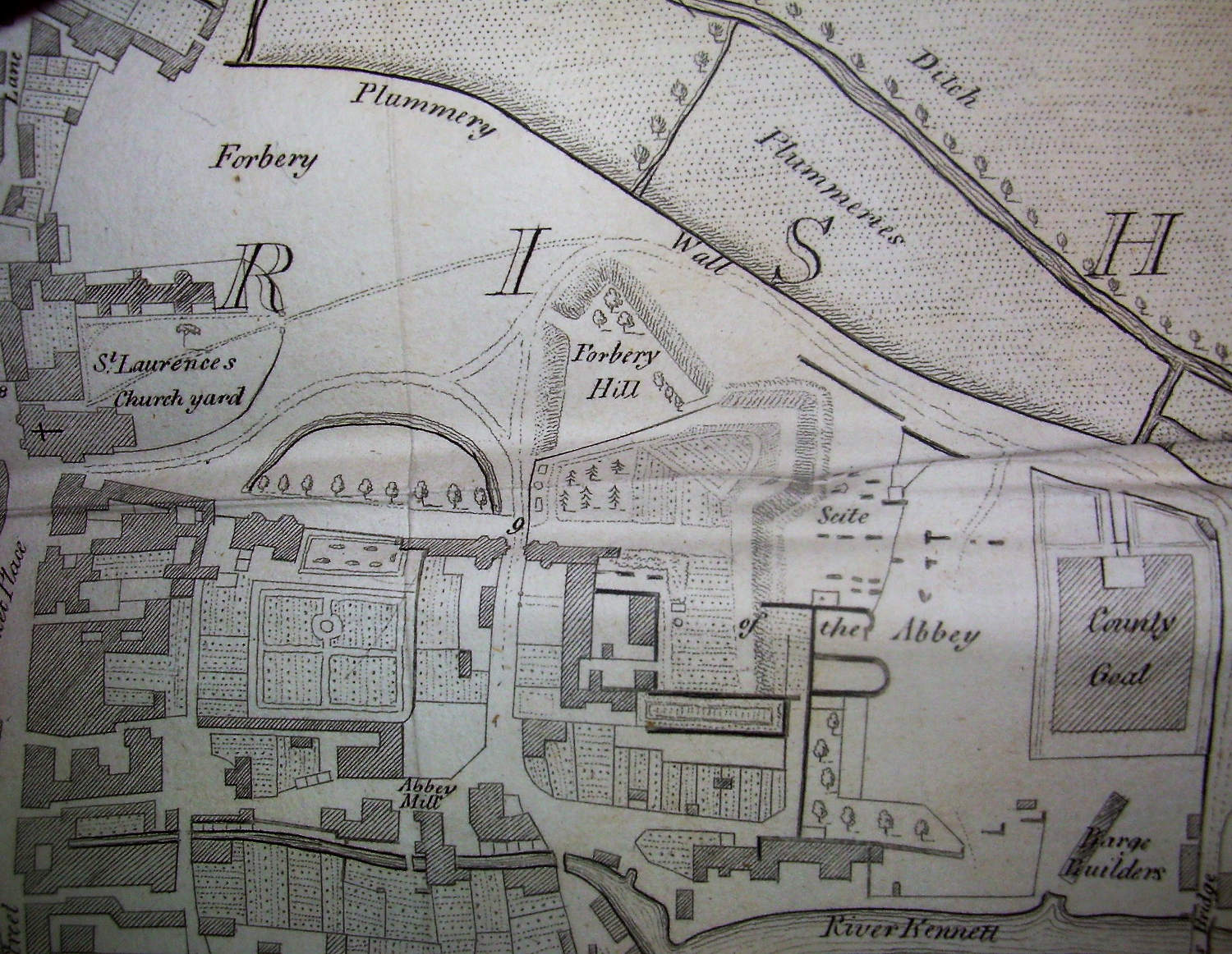

Reading and Caversham from John Rocques Map of Berkshire 1761 (TNA, MR1/677)

Parliament held Reading until evacuating it again October 1643, but did little to improve the defences. The royalists immediately retook the town and set about strengthening the fortifications, though apparently not those on the north side. In May 1644 with the approach of two parliamentarian armies, the royalists withdrew and over the summer the town’s defences were improved by Parliament.

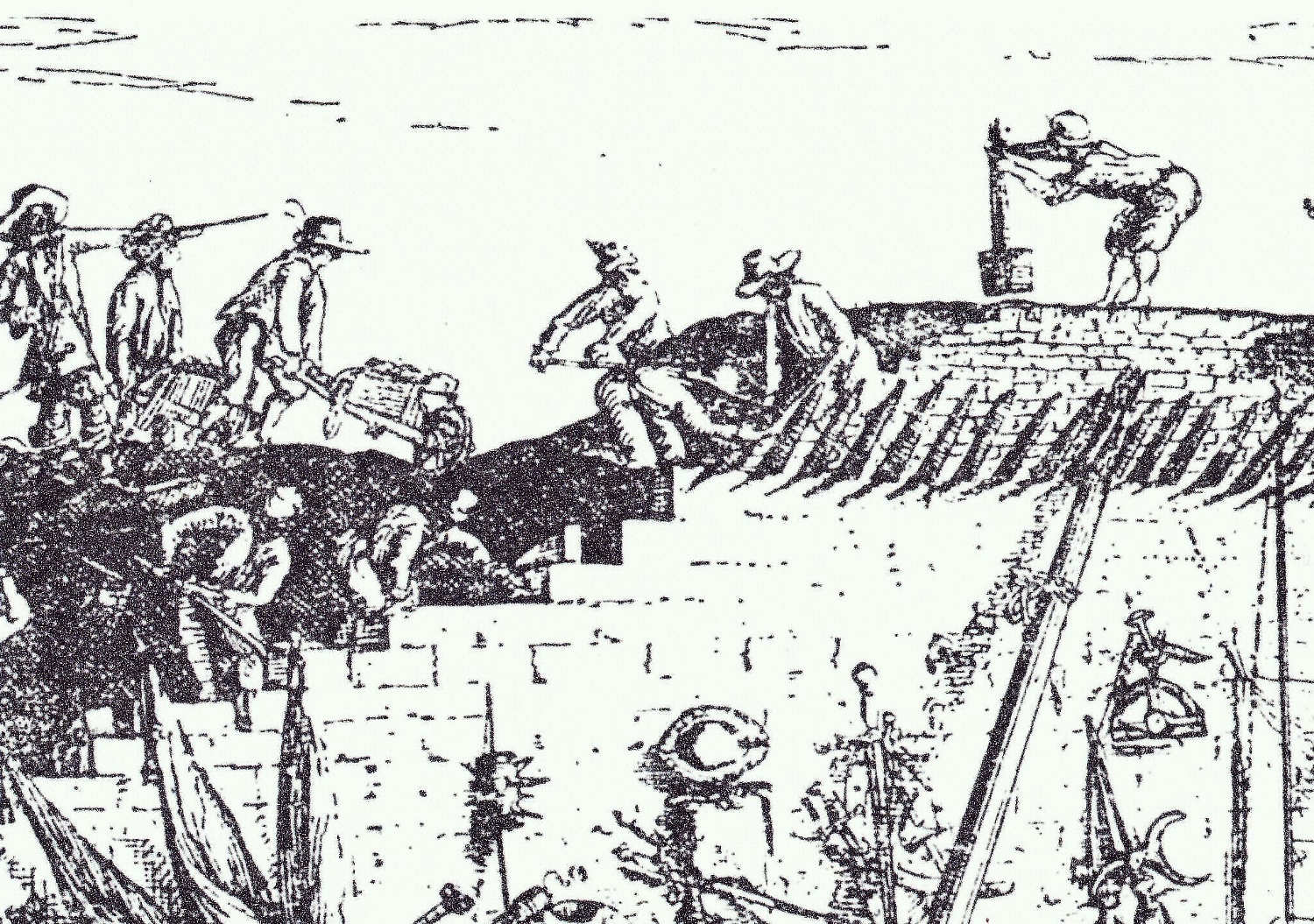

Building fortifications (detail from H Ruse, Versterckte Vesting (The Strengthening of Strong-holds), 1654

This included the building of forts around the Abbey and it seems likely that the Forbury fortification, the remnants of which can be seen today in Forbury Gardens, was built at this time. This work is portrayed on Tomkin’s 1802 map of Reading and possibly used the royalist bastion built on that side of the defences in 1643 within its construction.

Much archaeology has been undertaken around the Abbey and some of this has revealed glimpses of the Civil War defences. Work in the 1970s found a ditch, which seemed to run south-east to north-west, tentatively interpreted as being from the Civil War around 50m east of St James’ church. This could be the line of the royalist defences. Other investigations in the late 1970s and early 1980s revealed the ditch of the fortification shown on Tomkins’ map ending at the north wall of the refectory. Another 7.5 metre wide ditch running east-west to the south of the refectory was also found. Finally core sampling by Reading University of the Forbury mound in 2017 found it was partly made up of late medieval building debris, probably from the Abbey, suggesting it was of Civil War origin.

Tomkins map of Reading 1802 showing the Forbury Fort (from C. Coates, The History and Antiquites of Reading, 1802)

The Forbury fort is unusual as it is built around the remnants of the Abbey. Seventeenth century military theory and practice would have suggested the Abbey walls around the fort be pulled down to give the defenders a clearer line of fire and it is uncertain why this did not happen. Whilst Reading might lament the Abbey’s destruction, the survival of what remains is remarkable as the building of the defences and the 1643 siege could have caused much greater damage than they did.

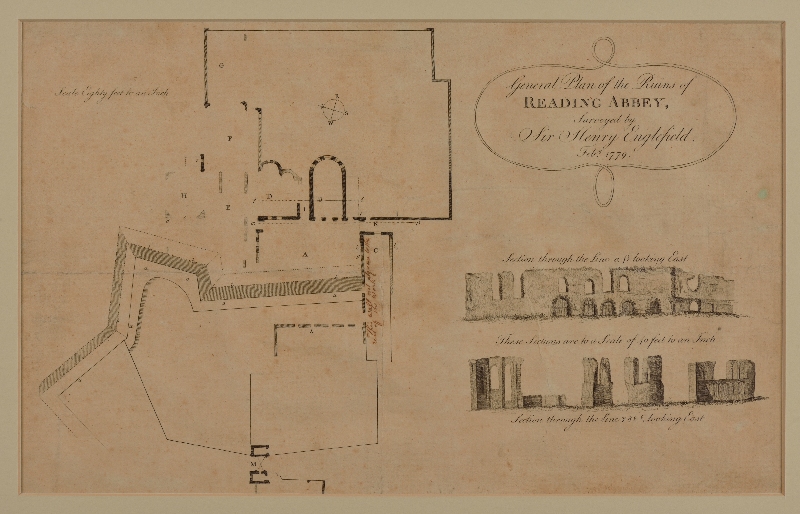

Civil war defences around Reading Abbey by Englefield 1779