Guest blog written by Julian Scola

7am. 296 Henley Road, Reading. Tuesday June 11.

A knock on the door! Two plain clothed police officers came to arrest my father, Giorgio Scola, and his brother John. It’s the year 1940. Their offence? Being ‘enemy aliens’ – Italians living in Britain when Italy had declared war (just the evening before).

Photograph of George Scola (right) with his brother and mother, taken in the garden of 296 Henley Road, 1949-50. Image credit: Julian Scola

Arrest

Giorgio, aged 23, despite living in Britain since 1922 and being educated in English schools, would not see his mother for five years. This blog is based on his diary chronicling his wartime years.

“We are taken by car to Henley Police Station where our papers are examined and [then to] Reading Barracks… We spend the morning … under guard — here we meet a dozen or so Italians and Germans of the district.”

After staying in temporary camps in Paignton and Bury, Giorgio is informed that he, but not his brother, will leave the next day. “I feel very depressed leaving John and everybody else I know”.

He is taken to Liverpool and boards the liner, Arandora Star. He writes “after a scramble to eat well after midnight (in the terrible confusion on board), I try to get some sleep — it is very hot and cramped and I sleep in my clothes… we are very much overcrowded”.

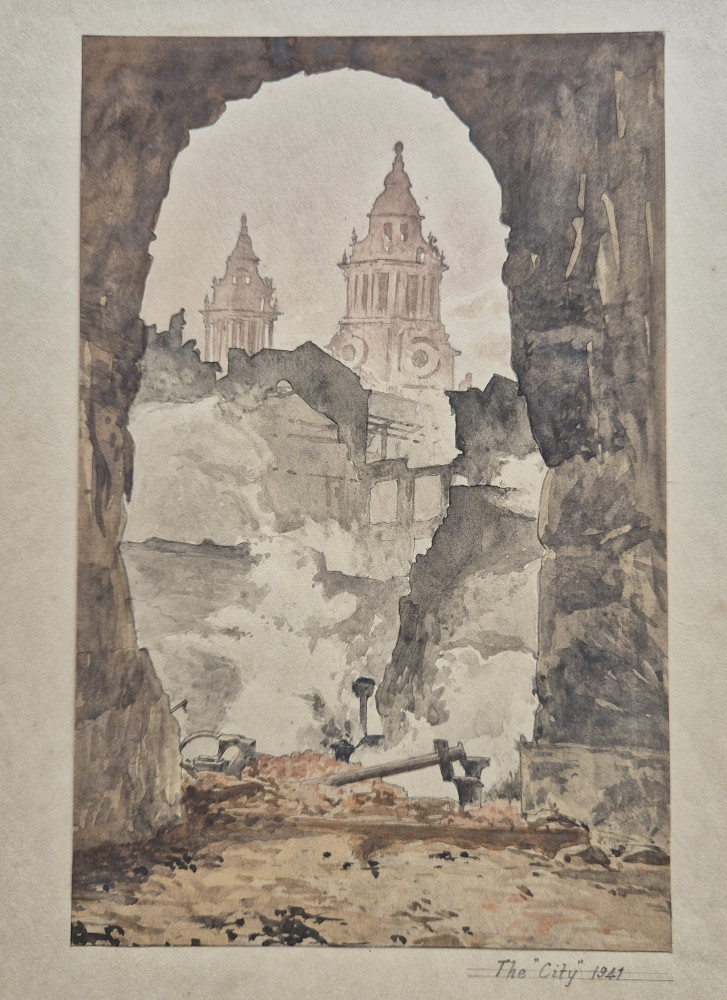

Watercolour by George Scola showing bomb damage in London during the First World War, 1941. Image credit: Julian Scola.

Torpedoed

Two days later he writes "whilst dozing round about 6.50 am. I am shaken by a loud dull thud which makes the whole ship tremble, whilst the lights go out simultaneously. I realise that we have either been mined or torpedoed … without losing a moment I wake up the one man still asleep in the cabin and help him to find his life belt in the pitch darkness, as well as putting on my own.”

He reaches the upper deck, and climbs down a rope tied to the rail. “I lose my grip and fall into the water very close to the side of the ship. I cough and splutter in the salty water, but luckily two pairs of helping hands soon attempt to haul me aboard … and with a superhuman effort on my part they manage to haul me in puffing and exhausted.”

Around midday a plane spots the survivors and by 4pm they are picked up by a Canadian destroyer. “I get some cocoa and shed my wet clothes in exchange for a warm blanket in which I doze … for an hour or so. Then I go down into the boiler room to dry out but find I have to stay down there for the night.”

The next morning, they disembark in Greenock, Scotland. “Bare-footed and ill-clad most of us 254 odd Italian survivors are paraded out on the cobbled quay in the cold morning … About 500 Italians have perished”.

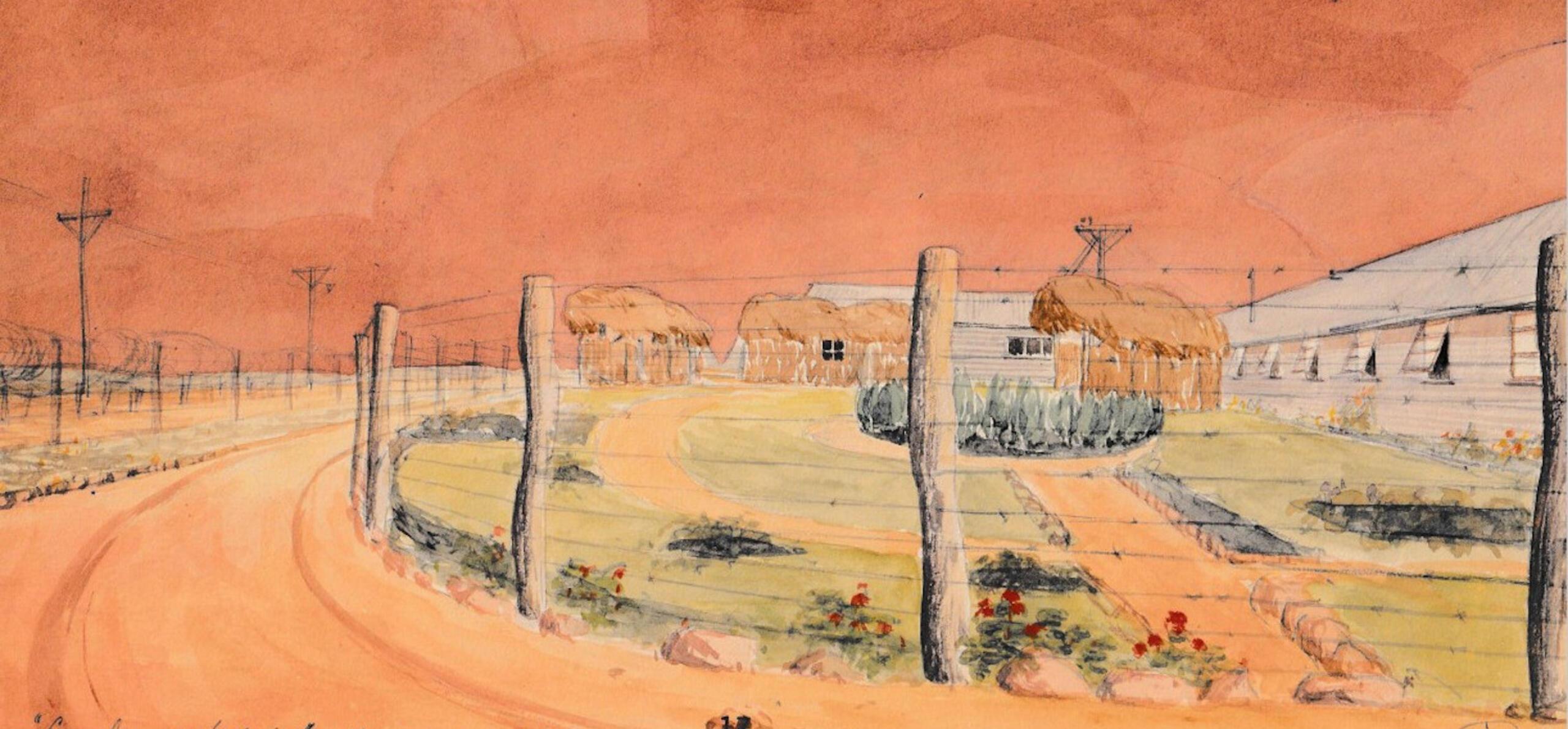

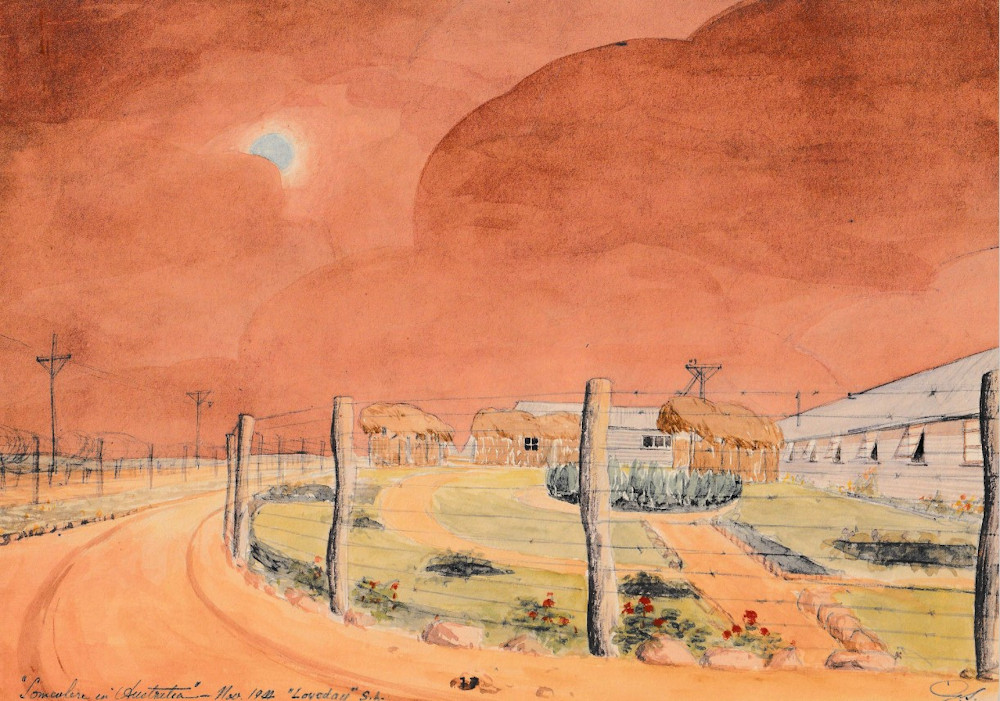

Watercolour titled 'Somewhere in Australia...' painted by George Scola whilst being held in Loveday internment camp , South Australia in 1944

Deported - again!

Just eight days after the sinking of the Arandora Star, the survivors are escorted under armed guard to another ship, the Dunera, “before going up the gangway we are one by one roughly manhandled … Any word of protest is greeted by a blow… we are roughly hustled below… to our allotted tables in one large mess room … over 200 of us in a space about 50 ft x 30 ft x 7 ft in height.”

On its journey the Dunera narrowly avoids being torpedoed. “We are horrified to hear a loud explosion, quickly followed by another - our nerves already on edge with the previous experience… all make a rush for the door … which is found to be locked - there are shouts and cries but all to no avail … The air is stifling, and I am almost crushed - everyone fears the worse… several soldiers rush up pointing fixed bayonets … tell us to calm down”.

The internees are eventually told that they are heading for Australia. Conditions on the Dunera were cramped, sanitation inadequate, and internees were robbed and some assaulted by their military guard.

George Scola (bottom left, wearing a beret) photographed in Tatura interment camp, Victoria, Australia, 1943. Image credit: Julian Scola

Down Under and back to Reading

My father was held for four and a half years in internment camps in Tatura, Victoria, and Loveday, South Australia. He felt well-treated by the Australians, who provided basic camps with decent accommodation and sanitation, and plentiful food.

On Christmas Eve 1944 he got permission to return to Britain, “cooled off very impatiently for another few weeks” in a tented camp near Sydney, and in March boarded a ship for Liverpool. He arrived in April and was sent to the Isle of Man. “We wondered whether our internment would ever end. The weeks passed slowly… we were still cooped up behind barbed wire”.

In late August he was released and returned to Reading “What a delight it was to see my mother again and embrace her!”

Giorgio Scola lived in Reading for the rest of his life. He was naturalized British in 1953 and worked for many years for the Civil Service in offices in Whiteknights and Coley. He married Fiammetta in 1950, living first in Windermere Road and later in Earley, and had three children Charles, Marina and Julian (two still live in Reading).

George, as he become known, loved England, never expressed resentment over his wartime treatment, and said that he was safer and better fed in Australia than many people who lived in London through the war.

He regularly attended masses at the Italian Church in Clerkenwell to commemorate those who died in the Arandora Star tragedy. George died in 2006.

Julian Scola was born and brought up in Reading. He now lives in Belgium but still visits regularly.

To read a fuller account of George’s story, download the below PDF '12000 miles behind barbed wire’ featuring much more of his diary, illustrated with watercolours and drawings he made in Australia.