Today, Reading is a vibrant and culturally diverse town.

Whilst it is sometimes assumed that Reading’s black history only began in the 20th century, when people arrived from the Commonwealth (such as the Windrush Generation), the reality is much different, from ancient beginnings through the Roman Empire, to the cruelty of the transatlantic slave trade.

In this blog, we look back at centuries of black history in and around the Reading area, using research and information discovered by Reading Museum staff, volunteers and partners over the course of recent years.

Roman Britain

Black people have been present in Britain since the Roman conquest almost 2,000 years ago.

The Roman Empire covered most of western Europe and the Mediterranean, and brought together geographically and genetically diverse communities through trade and military conquest.

Across Britain, archaeologists have found traces of incomers from many different parts of the Roman Empire, including North Africa, Spain, Turkey and Greece, as well as France and Germany. This evidence often takes the form of objects like Roman inscriptions, as well as Roman burial sites in cities like York.

The diversity of the Roman Empire would likely have been reflected in the population of Roman towns and cities like Calleva (now the village of Silchester near Reading), which was the centre of the Atrebates region of southern Britain.

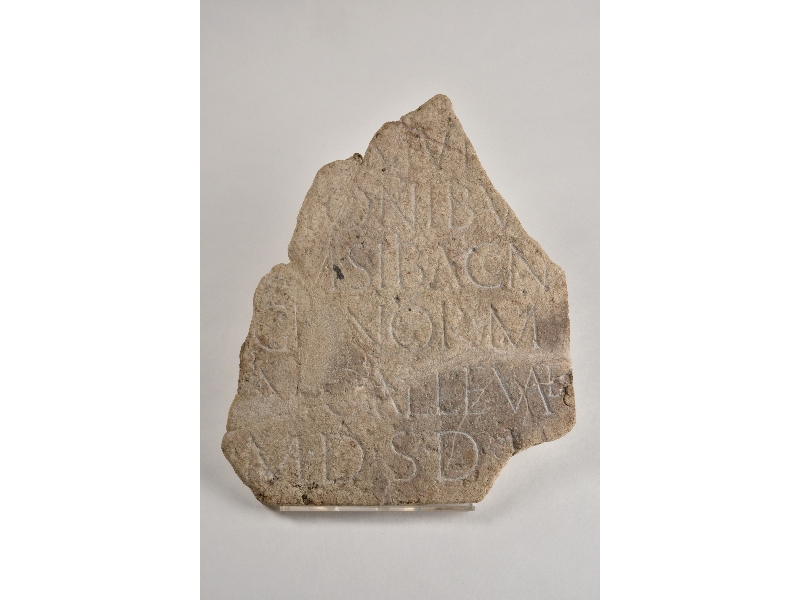

In fact, in 1907, archaeologists from the Society of Antiquities found concrete evidence showing that residents at Calleva had come from other areas of the Roman Empire. Whilst excavating a temple within Silchester’s walls, three inscriptions were found mentioning the guild of peregrini, a ‘guild of foreigners’, which we interpret as being an association of non-Atrebates trading within the city. The finds from Calleva are displayed in the Museum's Silchester Gallery.

The first recorded group of Africans in Britain were soldiers posted to Hadrian’s Wall. These were recruited in the Roman province of Mauretania (modern day Morocco), and were identified in a fourth century inscription at Aballava (a Roman town along Hadrian’s Wall, and Burgh-by-Sand today) as Numerus Maurorum Aurelianorum, ‘a numerus of Aurelian Moors’.

You can learn more about this on the Romans Revealed website, a project exploring the diversity of the people of Roman Britain, in which the University of Reading is a project partner.

A temple at Calleva had three late 1st century AD or early 2nd century AD inscriptions dedicated by the guild of peregrini, you can see this one in the Museum's Silchester Gallery. Museum object nos. 1995.1.18, 19 and 20

Reading's links to the slave trade

In the fifth century AD, links between Britain and Africa closed with the collapse of the Roman Empire in western Europe, and over the next 1,000 years very few Africans came to northern Europe.

In the Tudor period, exploration through new sea-routes began bringing greater trade with Africa and other parts of the world. This was also the origins of the transatlantic slave trade, where Europeans bought slaves in Africa to work on plantations in their new colonies in the Americas.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, Reading was a thriving market town, a regional centre for business and trade. Britain was prospering from growing international trade, and Reading merchants like sailcloth maker Musgrave Lamb were profiting from these global connections. Lamb’s large factory on Katesgrove Lane by the River Kennet produced exceptionally strong white sailcloth, and Reading sailcloth was supplied to the East India Company, which had gradually seized control of large parts of the Indian sub-continent. Their ships traded luxury goods like tea and spices between Europe and Asia, and their cargoes also included West African slaves.

Southcote Manor House, Reading by Edgar Leuchars, 1912. Museum object no. 1931.218.1

Caribbean Plantations

Reading had other connections with slavery.

Before the inhumane trade was fully abolished in 1834, several wealthy Reading families had investments in Caribbean sugar and cotton plantations where the work was done by slaves.

The most prominent Reading family to have such connections were the Blagraves or Blagroves. They had lived in Reading since the 1500s, with estates in Southcote and Woodley. The mathematician John Blagrave, who died in 1611, has a memorial in Saint Laurence’s church and is commemorated by Blagrave Street.

The Blagraves' connection to slavery came through John’s nephew, Daniel Blagrave. Daniel was MP for Reading, and during the 1640s he became a prominent supporter of the Parliamentarian forces during the English Civil War. After the end of the war, and the execution of King Charles (for which Daniel Blagrave was one of the signatories), Daniel was rewarded by Cromwell and given lands in Jamaica. Daniel’s family developed Cardiff Hall and other Jamaican plantations which were worked on by slaves. The family owned these estates until the 1950s. The Berkshire Record Office holds documents relating to these Jamaica plantations.

Cardiff Hall, Jamaica, between 1820 and 1824, by James Hakewill (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Enslaved servants

In the 1700s, it was fashionable for wealthy families in Britain to have enslaved black servants. These servants were some of Reading’s first black residents. They were not allowed to use their real African names and were given new European names, usually taking the surname of their owners. Local parishes registers record the baptisms and burials of some of these enslaved servants. For example, on 13 January 1777, the Register for Saint Laurence’s church, Reading, records the baptism of Scipio Smith, who was originally from the coast of Guinea in West Africa, and was a servant of Mary, daughter of Joseph Smith Esq. of Kidlington.

The Loveday family had a black nurse called Dorothy Blake, or ‘Black Doll’, when they lived at Caversham Court (then known as the Old Rectory). Dorothy had been enslaved in west Africa and given to Lady Hopkins, who was the aunt of John Lovegrove. The family commissioned a portrait of their ‘highly-respected’ nurse and provided a legacy for her until she died in 1780.

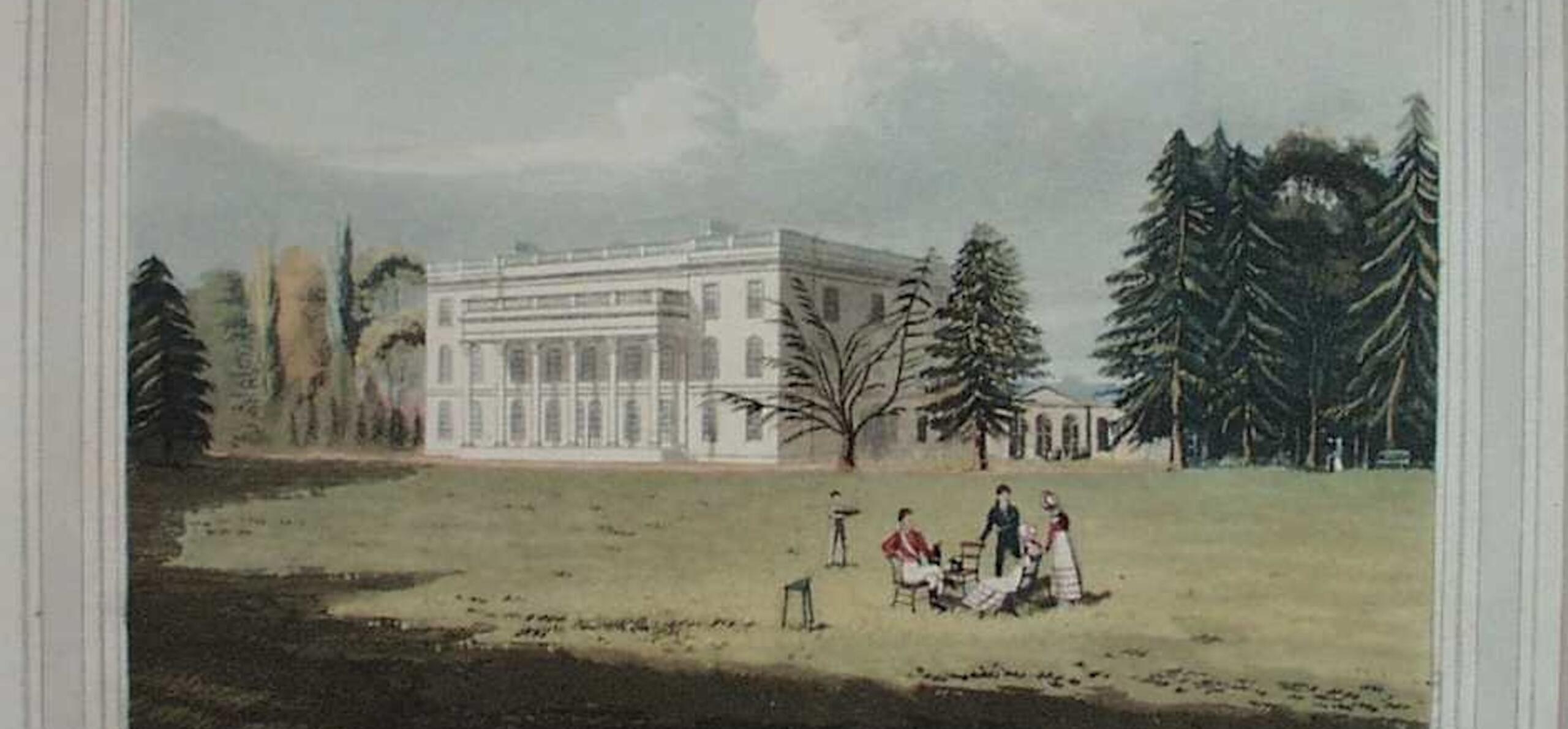

In 1784, black butlers, Indian coachmen and mixed-race footmen were working at Caversham Park for Major Charles Marsack. Marsack had returned to Britain after fourteen years' service as an officer in the Bengal Infantry in India. He bought Caversham Park, and lavishly improved the house and grounds. He was one of many ‘nabobs’ who served in India with the East India Company and settled in the Thames Valley. In fact, so many settled in the area that it was called the ‘English Hindoostan’.

Caversham Park, Reading, print on paper, artist Edward Dayes, engraver W. and J. Walker, 1793. Museum object no. 1974.116.1

Country Houses and the East India Company

The East India Company led a complex global trading network across India, South East Asia and China. It was overseen by directors based in London, governing territories greater than the British Isles in size and population and generating vast wealth and power. Between 1700 and 1800, at least 229 landed estates were purchased in Britain by those who had made their fortune either as employees of the company or as independent merchants in India. Around Reading, these estates included Basildon Park (now owned by the National Trust), Maiden Erlegh (on the site of today’s school), Purley Hall, and Caversham Park.

While many people made their wealth though these colonial and slavery trades, others were increasingly horrified by this exploitation and actively campaigned for the abolition of slavery. You can find out more about Reading’s links to the transatlantic slave trade and abolition movement in the Reading International Solidarity Centre (RISC) online exhibition. This was created in 2007 to mark the 200th anniversary of abolition of the British slave trade in 1807.

Reading Cemetery, Berkshire. Published by Rock and Co, London, 1865. Museum object no. 1974.465.1

Missionaries in Australia and Africa

Throughout the 19th century, many Reading residents were involved in foreign missionary work. Missionaries would travel across the globe with the aim of spreading Christianity to ‘heathens’ and thus focused on areas they believed had ‘uncivilised’ people. Mostly this evangelical work was done alongside colonial expeditions. The missionaries sometimes returned home with children and young people they had ‘adopted’. Reading Cemetery, which opened in 1843, contains the graves of many people who came from countries that had become part of the British Empire.

One of these individuals was Australian Aboriginal Willie Wimmera who was born in 1841. His people, the Wotjobaluk, were swept off their lands in south-eastern Australia by 30,000 British colonists. Willie witnessed his mother’s murder and the seizure of his homeland and was forced to become the servant of Horatio Ellerman. He escaped Melbourne and was ‘adopted’ by an Anglican missionary, Septimus Lloyd Chase. The pair sailed for England in 1851 and stayed with Chase’s family at 179 King’s Road in Reading. Willie contracted severe congestion of the lungs and died on 10 March 1852.

Mary Smart was one of two girls sent to Reading from Sierra Leone in 1848 to train as a teacher. She died in 1849 and was buried on 13 March in an unmarked grave at the cemetery. The burial records at the Berkshire Record Office describe her as ‘a pious African girl’, daughter of John Smart. His real name was Okoroafor, a member of the ruling family of Imo State in eastern Nigeria. He was captured by slave traders in 1816 but was rescued by a British frigate and released at Freetown in Sierra Leone. Okoroafor took his European name from two men – Samuel Smart, Governor of Sierra Leona from 1826 to 1828, and John Weeks, a missionary who converted Okoroafor to Christianity.

Many more stories about Black Britons are coming to light as researchers study the records in archives, and there will be many more discoveries linked to Reading and the region in the years to come.

Sources and further reading

David Olusoga , 2020, Black and British – a short, essential history

National Trust, 2020, Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust

Reading International Solidarity Centre (RISC), 2000, Global Reading map

Sarah Markham and H. Godwin Arnold, c.1980 A History of Caversham Court, Reading, Reading Civic Society

Reading's slave links guide - RISC teamed up with Aspire CIC, a Reading-based organisation representing the Caribbean and people of Black heritage, to explore the town’s links to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Download the guide from their website.