'You don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone'

As part of the High Street Heritage Action Zone programme, a four-year project that is being funded by Historic England and Reading Borough Council, we are bringing you another fascinating two part guest blog by Katrina Parker and Margaret Simons of the Reading Conservation Area Advisory Committee. This time we will be exploring Reading's third HSHAZ: Castle Street and St Mary's Butts.

The heritage of Castle Street and St Mary's Butts

For centuries, Reading’s geographical position at the confluence of the rivers Thames and Kennet and its road and later rail network have been at the centre of its ability to thrive and meet the demands placed upon it by change. The Castle Street and St Mary’s area is no exception to this, having also the old highway to the west and St Mary’s Minster at its heart. It is in this area that the early Anglo-Saxon settlement and the origins of what we know as Reading today is believed to have been located.

There are two references to Reading made in the Domesday Book of 1086, but it is the one under that of Battle Abbey that is of most interest. It mentions an estate which lay to the west of the town and included 28 dwellings and 12 acres of meadow.[1] It also includes a church, which had substantial income and would have been the forerunner of the later St Mary’s parish church. A church was in fact established here sometime after the late sixth or early seventh century, one of 25 founded in Berkshire. The site was chosen precisely due to its situation north of the Holy Brook and the Seven Bridges crossing over the river Kennet. The term minster was in use by the 10th century denoting a church of importance by the time of Domesday and archaeologists have unearthed a coffin containing 9th century coins from the present-day churchyard. This minster church would have drawn its congregation from a wide area and assumed an importance that extended beyond that of a religious centre, having both an economic and social impact on the small, but expanding settlement. [2]

From the early establishment of a market outside the west door of the minster church for the convenience of the congregants the area has developed over the centuries, continually evolving to meet the demands of the local population. Much evidence of this rich history is still apparent in the mix of remaining buildings, many from different periods, quite a few of which are listed. The stories of some of which we will explore in this blog.

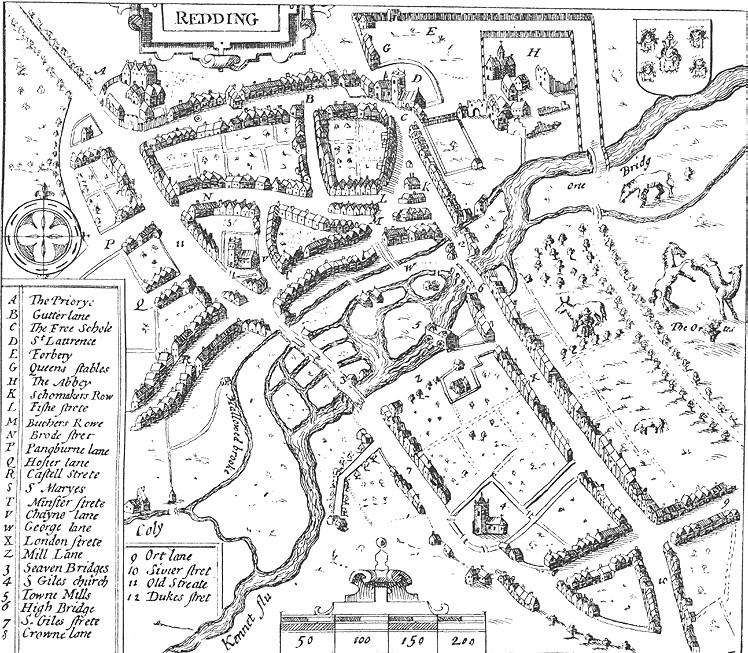

John Man’s map of Reading 1813, shows Minster Street, St Mary’s Butts and the Castle Street area. Note how well built up the area is and yet to the west and close by, open fields and agricultural land is still abundant.

Early History

The foundation of Reading Abbey in 1121 had a profound impact on St Mary’s. Not only was the Abbot of the Abbey rector of St Mary’s until the dissolution in 1539, but the Abbey’s establishment of a new market to the east by, at the latest the early 13th century, would have impacted the wealth of the earlier market area. The area outside the west door of St Mary’s was by c.1160, known as Olde Street and the market became known as Old Market, differentiating it from the Abbot’s new market. During the reign of Henry VI (1422-1461) a road was described as ‘a certain street ex antique called Olde Street’ which ran southward towards Southampton and Winchester and northward from the Seven Bridges through the present-day St Mary’s Butts towards Caversham Bridge. [3] At some point between John Speed’s map of 1611 and Man’s early 19th century map, Olde Street became St Mary’s Butts, the name it is known by today. [4]

Minster Street was so called by c.1240, but during the early part of the 17th century gun making starts being recorded in this part of the town and at some point, perhaps as early as c.1650 the western end becomes Gun Street. [5] On John Speed’s map of 1611 Castle Street is clearly evident, but it had assumed this name sometime between 1250-1275. [6] Whilst it may be possible that some fortifications existed as William the Conqueror gained control of major routes to the west, there is no evidence of a castle in the area.

Church of St Mary, St Mary’s Butts

Since 1999 the church of St Mary has been known as Reading Minster and whilst the main body of the church dates from the 11th century much of what is seen today is of a later date. Major work was done to the church 1551-1555, post reformation, with materials reclaimed from the Abbey church. From this period is dated the large west tower with its fine flint and stone chequer work, but much of what we see today is almost all Victorian. However, as well as a Saxon doorway there is still in existence evidence of work from the 1300s namely the Jesus Chantry in what is now the north transept and a 13th-14th century arch framing the choir vestry door that marks the site of the altar dedicated to the “Fraternity of the Guild of Jesus”.

St Mary’s still is, in the 21st century, a very busy church with two services a week and additional daily prayers. The church works with a number of organisations to provide spiritual help and hospitality at both a community and civil level.

The Post Medieval Early Modern Town

Slade in his discussion of the medieval borough refers to the corner opposite Minster Street, where Castle Street began the main road to the west, as being the busiest in the town. [7] On Speed’s map of 1611, we can see Castle Street is already lined both sides with buildings and stands out as one of the town’s principal thoroughfares. Little remains in Castle Street that is visible from the time of Speed's map, save two probably 16th century buildings, nos 15 and 17, and of a century or so later the Sun Inn and what is now the Horn public house.

John Speed’s Map of Reading, 1610

Nos 15 and 17 Castle Street

Both houses are on the south side of Castle Street, they are three-storey gabled buildings, each story slightly overhangs the one below; the top story of both is partly in the roof. The walls are of half-timber covered externally with pebble-dash stucco, and the roof of both is tiled. In their time these houses would have been high status residences built to represent the wealth and standing of their occupants.

In a lease dated 1527 no 15 was described as a tenement with garden, the lessee being one William Style, a burgess of the borough. [8] In the 19th century John Cecil Blandy a brewer and wine merchant resided there for a time, but earlier that century it had been the office of Mr J. Omer Cooper auctioneer and estate agent and the premises of Miss Higham’s ladies seminary.

No 17, also known as Lyndford House, currently occupied by Rowberry Morris solicitors, is the larger of the two properties it having a carriage way on the east side. From a 1923 sale catalogue it is described as a freehold Elizabethan residence with factory premises and outbuildings. [9] The interior has been altered and modernized, but original features from earlier periods still remain. In the front is a c.17th century restored wooden entrance porch. During the 1840s and 50s the building was home to Thomas Rickford a retired Royal Navy purser and brewer, who was mayor of Reading 1840-41. Sometime during the early 1850s the house was leased by Thomas Hawkins brewer, he was followed by his son Hugh and it remained in the family until the end of the century. By 1901 it was the home of Dr Percy Howse.

Before the renumbering of Reading Streets in the 1870s nos 15 and 17 were 139 and 138 Castle Street respectively. It is this renumbering that gives rise to the common misconception that no 17 was a public house known as the Castle Inn/Tavern which was in fact on the north side of Castle Street and later became no 28. [10]

15 and 17 Castle Street (Wikimedia Commons)

The Sun Inn

Whilst no 17 may have had a short-lived existence as a hostelry the Sun Inn at 14 and 16 on the north side of Castle Street seems always to have performed this function. As the Rising Sun, it was one of a number of inns in Castle Street that overtime served the coaching and carrier traffic of the town. It is a refronted timber framed and stucco gabled c.17th century building, but has earlier foundations and cellars. The latter are thought to be remains of the old Reading county gaol. An ancient doorway gave access to a large hall which had provided stabling for many horses over the centuries, but these collapsed in 1947.

15 Gun Street

This 17th century building has some timber framework, but has been much altered since, particularly at the beginning of the 19th century. Today it sits well below the current road level, a feature that denotes the original level of the road which was raised in the early 19th century. Since at least the 1830s the building has been a town pub or eatery. Its first known name was The Old Dolphin and at the time it abutted one of the town lock ups. From the 1830/40s it was renamed The Shades, a name it retained until it closed as pub in 1958. From 1971, when it became an English Grill, it has been an eating house of various genres and names ever since. Today it is home to a B.B.Q cooking establishment called Bluegrass.

Georgian and Victorian Change and Development

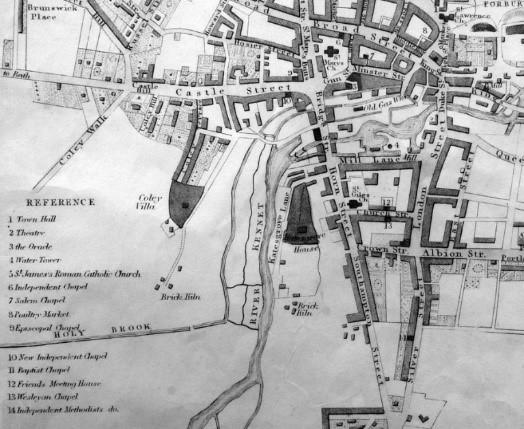

Charles Tomkins’ map of Reading (cropped) from Coates, C. The history and antiquities of Reading, 1802.

At the start of the 18th century Reading was a fairly wealthy, ‘rather shabby country town’. [11] Its economy had been slow to recover from the English Civil War and the decline of its clothing trade. Without establishment of any replacement industries, there followed prolonged poverty for the town and only when it began to evolve as an important marketing centre did the economy begin to thrive once again.

Reading was mostly contained within its medieval boundaries until the end of the 18th century, when once again it began to prosper as a market town and had malting as its main industrial activity. Its new found prosperity was reflected in its streets and buildings and its market, regarded as one of the best in England. It dealt with many kinds of agricultural produce, providing livelihoods not only for the town’s market traders but also seedsmen, mealmen, purveyors of consumer goods which in turn created the need for bankers and solicitors etc.

At a time when Bristol remained England’s second city, Reading was well placed as a trading centre and benefitted from its excellent communications, being on the direct route from London to the West Country and only a mile or so from the River Thames. Successive improvements in water transport and the Thames Navigation at the time of the industrial revolution, which gave access to Wales and the North, was closely bound up with the town’s increasing prosperity during the 18th century. The completion of the Kennet and Avon Canal in 1810 which connected Reading to Bristol enabled, not only, the opportunity to purchase cheaper, mass produced goods, but the export of the area’s agricultural produce. By 1835, 50,000 tons of goods were moving in and out of the town, 100 tons by road, the rest by water. [12] Even when rail transport was beginning to compete with the waterways in the 1850s, a large amount of goods continued to come into and out of the town by water transport.

Snare’s 1840 Map of Reading – (cropped) (BRO via Get Reading)

Minster Street, Gun Street and St Mary's Butts

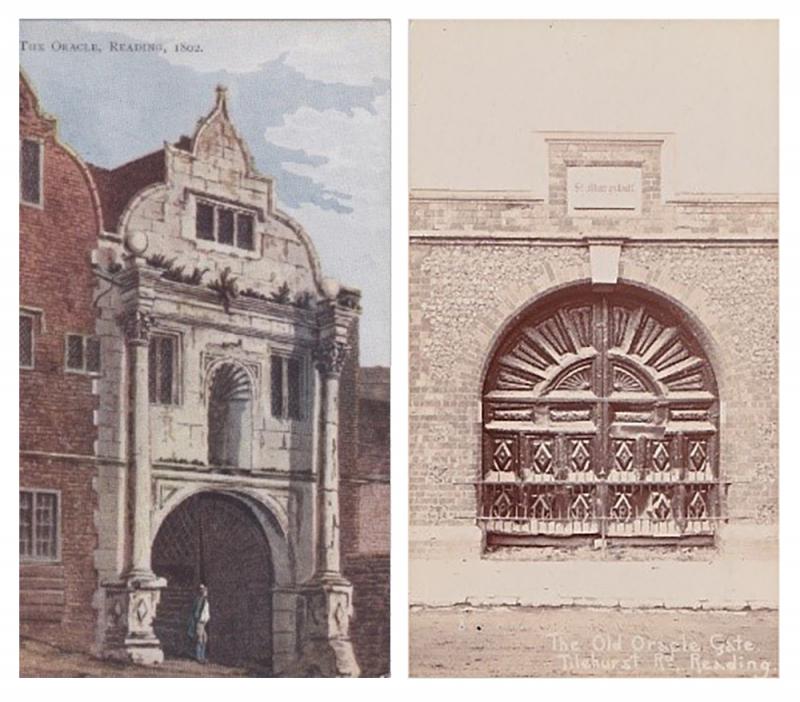

The Oracle 1802 (l); Oracle Gates, St Mary’s Hill, Tilehurst Road (r) (Author)

Today, Minster Street acts as one of the main drop off and pick up points for Reading buses and is commercially a relatively quiet street, which is very different from the 18th century and its heyday in the early Victorian era. Until the middle of the 19th century the most well-known feature of Minster Street was the Oracle Workhouse. Founded in the 17th century under the will of John Kendrick, it stood on Gun Passage corner opposite The Old Dolphin. When the workhouse was finally pulled down in 1850, it was replaced by retail shops known as St. Mary’s Parade. However, with the opening of the Railway in 1840, the town’s epicentre shifted and although Minster Street was still important, it had gradually declined by the 20th century. The corner now forms part of the Oracle Shopping Centre entrance way. When demolished the impressive Oracle gates stood in a wall on the Tilehurst Road until they were moved to Reading Museum in 1962 and are on display in the Story of Reading Gallery. [13]

15, 13 & 14 Gun Street (Author)

Gun Street, named after the gunsmiths who made and traded their wares there from the 17th century, was built up on both sides until 1816, when the buildings on the north side were cleared to widen the road, allow for the extension of St Mary’s churchyard and allow for the raising of the street level.

Gun Street 1908 (Hylton, S., Reading A Pictorial History, image 44.)

1, Gun Street - a Building of Townscape Merit

In 1770, the Cross Keys Pub was mentioned as a place of cock fighting and the building was still there in 1816. It remained below the level of the new raised carriage way until 1877, when it was rebuilt to the designs of Brown and Albury. At the time the original lease was still held by the Blagrave estate and G.F Shadbolt was the landlord. It was sold by its brewery owners in 1989 and has since had a variety of names. Noted as Reading’s best Victorian pub, its fine exterior, which plays on the cross keys theme, can still be admired despite the surrounding street furniture.

1, Gun Street (Author)

9, Gun Street

Most probably built in the early 19th century rather than the late 18th, this 3-storey shop, of silver brick, has a rear yard that includes a listed, culverted section of the Holybrook and has been the home of the renowned Purple Turtle since its move from the southern end of London Street in 1996. [14] The club was fondly remembered by Game of Thrones actor, Natalie Dormer and James Corden, on his Late, Late chat show in America in 2015. No 9’s earliest known occupant was Henry James, an ironmonger, manufacturer of guns and a truss maker for ruptures specially adapted for sportsmen! His father, owned premises on the north side of the street until their demolition, when the business moved to the south side.

Purple Turtle (Author)

By 1851, Henry had been joined by his sons, Archibald and Nathaniel and was a town councillor. He retired from business in 1861 when Nathaniel, took over the running of the Wholesale, Retail and Furnishing Ironmongery. The business and building were sold in 1864 to Joseph Staples an established Wholesale, Retail, General Furnishings and Saddlers’ Ironmonger who was trading in Newbury. His son, John took over No 9 in the 1880s, but no longer lived over the shop and on retirement in the mid-1890s he sold it to George Cox. The Ironmongers was still there in 1931, under the ownership of John May who had run the business from 1909.

A continuation of the development of Georgian and Victorian Reading will appear in Part Two of this blog where our short walk will also bring us into the 21st century.

Thank you!

Thanks for joining us for the first part of our walk in time along St Mary's Butts and Castle Street. Part two, kindly provided by Katrina and Margaret continues our journey into the 20th Century and up to present day.

To view more images from Reading's past, take a look at our Online Collections or visit Reading Library's Online Catalogue or the Berkshire Record Office. You can also learn more about the Reading Conservation Area Advisory Committee by heading to the Reading CAAC website.

End Notes

[1] Slade, C., Historic Towns Reading (c.1969) p. 3.

[2] Dils, J., Reading A History (2019) pp. 3-5.

[3] The borough of Reading: The borough | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk) FN 15 Doc. penes churchwardens of St. Mary's Reading.

[4] The term Butts has a number of origins; one is with archery referring to the place yeoman undertook target practice, another the term used for an abutting strip of land often associated with the medieval field system.

[5] BRO R/AT3/19/1/1-2

[6] Dils, p.14; Slade, p. 5 fn51.

[7] Slade, p5.

[8] BRO R/AT3/2/1/1-7

[9] BRO D/ENS/BS 10

[10] Berkshire Chronicle 20 Jan 1849 p2; Dearing, p. 17.

[11] Phillips, D., The Story of Reading, p. 75.

[12] Petyt, M., The Growth of Reading, p. 85.

[13] Reading Evening Post 10/9/93 p9

[14] Reading Evening Post 13 December 1996 p. 27.