UPDATE, 19th April 2022: you can now view the Silchester Eagle in full 3D on the Reading Museum Sketchfab account!

One of the most famous objects found in the excavations of the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum at Silchester, near Reading, is a meticulously sculpted bronze eagle.

Whilst this proud bird stands at just 15cm tall, its wings both missing, it has maintained an awesome presence in England's collective imagination ever since its discovery in the 19th century.

In this blog, learn the story behind the Silchester Eagle, one of the most famous Roman eagles discovered from the time of the Roman conquest of Britain. Read about the discovery of this remarkable object, the significance of eagles in imperial Rome, and how this mighty Roman aquila continues to inspire today.

Why an eagle?

In ancient Rome, the eagle was known as the king of birds. It was a symbol of imperial power, and therefore represented courage, strength and immortality. The eagle remains one of the most famous animal symbols associated with ancient Rome today.

Most famously, the eagle, or aquila, featured on the standard of the Roman Legions. The standard bearer, the Aquilifer, would carry the eagle standard into battle. This was a hugely prestigious position within the Roman army.

The eagle was not the only animal of significance in Roman mythology. Another key animal from Roman mythology was the wolf, a powerful symbol of Rome's earliest days. The most famous example is the she-wolf (the Capitoline Wolf) that raised the legendary twins Romulus and Remus who became the city's mythical founders. The eagle represented something very different to the wolf: Roman military strength, power, and superiority over the Empire's foes.

The Silchester Eagle (museum number REDMG : 1995.4.1)

Where was the Silchester Eagle found?

This striking Roman eagle, as imposing as any ever found in Britain, was found at the site of the Basilica, the public meeting place of daily life, at the centre of the Silchester Roman town. It was unearthed on the 9th October 1866 during excavations led by Reverend J. G. Joyce.

Reverend Joycem, the rector of nearby village Stratfield Saye, was very interested in archaeology. He excavated at the Silchester site from 1864 to 1878 and recorded his work with fine illustrations in a three-volume journal.

When he discovered the Silchester Eagle, Joyce thought that he had found a great legionary aquila, buried in debris when the Basilica was destroyed. Perhaps it was hidden for safekeeping?

Today, we believe the Eagle was actually part of an official civilian statue, and likely ended its life as scrap, waiting to be melted down.

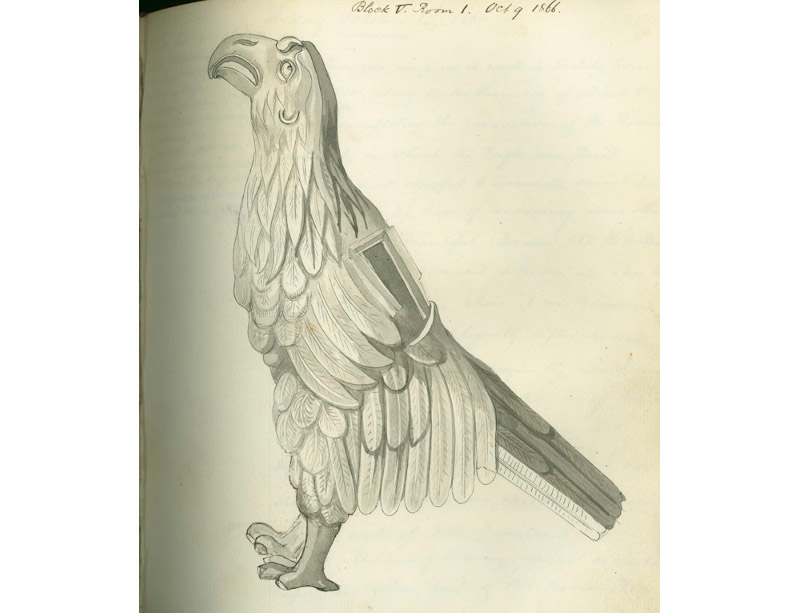

Drawing by Rev Joyce of the Silchester eagle in his journal

The design of the Silchester Eagle

Crafted in the 2nd century AD by a skilled craftsperson, the Silchester Eagle stands with its head raised and turned to the right. It would have had outstretched wings. The careful modelling of the feathers on the body suggests the wings must have been extended and raised.

In 1962, Jocelyn Toynbee, a British classical archaeologist who taught at University College Reading in the 1920s, described the eagle as ‘by far the most superbly naturalistic rendering of any bird or beast as yet yielded by Roman Britain’.

Detail of the body feathers and feet of the Silchester eagle

The Silchester Eagle was repaired during its lifetime, when replacement wings and probably new feet were fitted. It was then damaged again when it lost its wings and suffered damage to its replacement feet.

The curve of the underside of the feet suggests that the eagle’s claws once grasped a globe, probably held in the hand of a statue of an emperor or a god, like Jupiter (the god of the sky, within whose grasp the eagle would have surely found its natural home).

What has the Silchester Eagle inspired?

The Silchester Eagle was a significant inspiration of Rosemary Sutcliff's popular children’s books The Eagle of the Ninth and The Silver Branch.

The books focus on the mysterious disappearance of the Ninth Legion, Legio IX Hispana (the 9th Spanish Legion). The Ninth Legion was stationed in Britain following the invasion of 43 AD. However, by 120 AD, less than a hundred years later, the Legion had vanished from Roman records without a trace.

Sutcliff imagines what would have happened when the Ninth Legion's eagle was lost. This is because the loss of an eagle was of enormous importance in Imperial Rome. It represented not just the defeat of an individual Legion, but of the might of the Roman Empire itself. When eagles were captured by enemy forces, bloody battles would be fought to regain them.

Whilst we don't know what happened to the Ninth Legion, we do have thorough records about the movement of Legions and Auxiliary units across the Roman province of Britannia. We know about these activities from inscriptions (like the Vindolanda tablets) and later histories.

Head of the Silchester eagle

Discover the Silchester Eagle and more stories from Roman Silchester

To learn more about the Silchester Eagle and the astonishing history of the Roman town at Silchester, come and explore the Silchester Gallery at Reading Museum! The Eagle stands proudly on exhibit, alongside many other artefacts and displays chronicling the history of the town and the wider context of Roman Britain in which it was so important. Plan your visit to Reading Museum today, or view the Silchester Eagle in 3D on Reading Museum's Sketchfab.

Reference

Toynbee, J.M.C. (1962) Art in Roman Britain

The Silchester Eagle was purchased by Reading Museum from the Duke of Wellington in 1980 with generous support from Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund and the Art Fund. It is on display in the Silchester Gallery.