Just over one hundred years ago, in autumn 1918, the people of Reading were living through turbulent times. The First World War was drawing to a close, and the worst pandemic since the Black Death was sweeping through Europe: the 1918 influenza pandemic. Across the world, more than 50 million people lost their lives, and a quarter of the British population was affected.

The outbreak hit the UK in a series of waves, with its peak at the end of the war in November and December 1918. It is thought that the spread of the influenza virus was catalysed by the terrible conditions in the trenches of the First World War and returning soldiers who brought it home to the UK.

As the vaccine rollout for COVID-19 continues across the UK, join us as we look back at life in Reading in 1918, and explore how people then responded to the pandemic that changed their world, just as COVID-19 has impacted ours.

Wounded soldiers at Reading War Hospital, postcard, 1917 (museum no. 1996.197.95)

Reading and the First World War

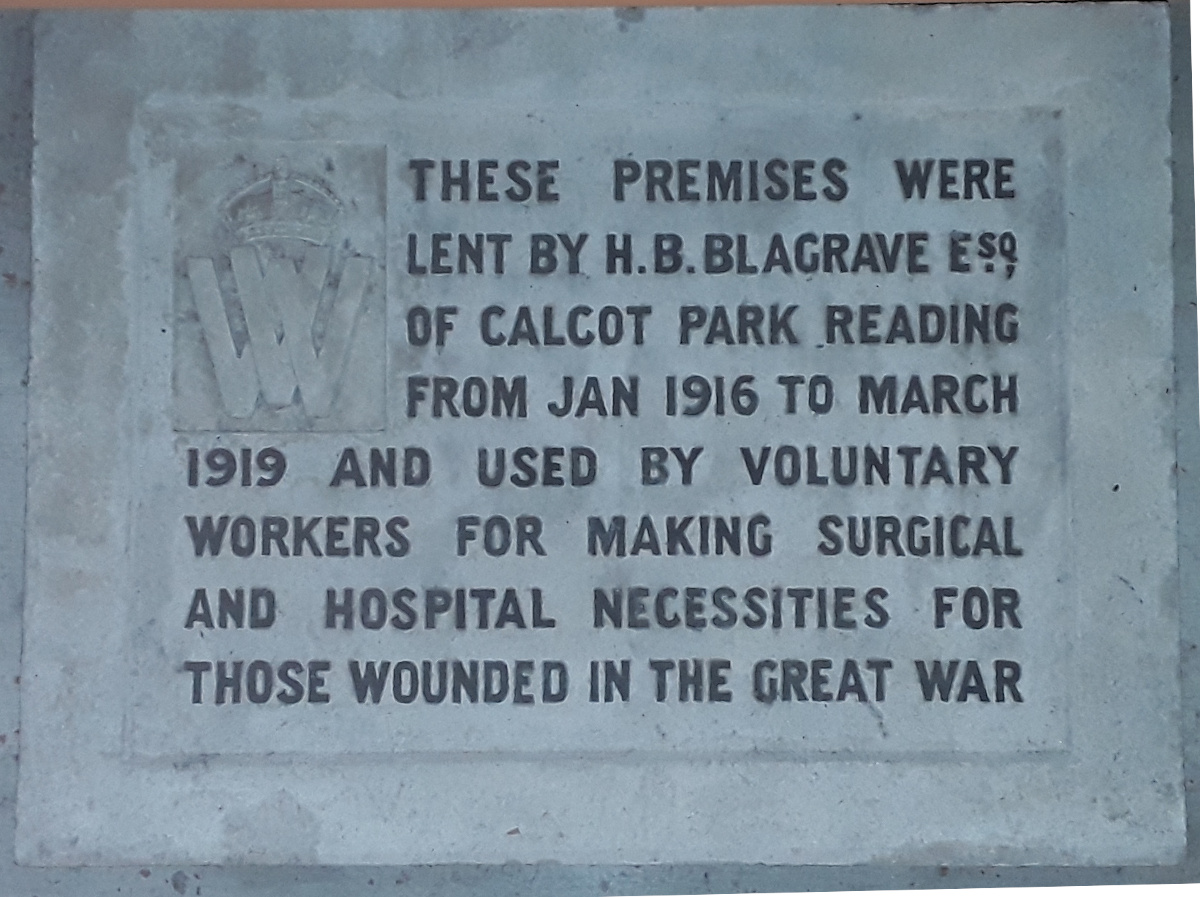

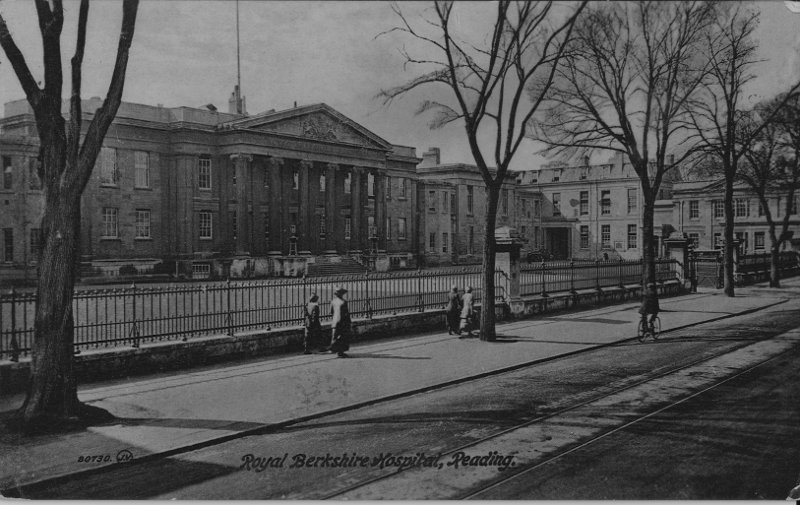

Reading had become one of Britain's main First World War medical centres, treating casualties sent to recover from the frontline. The outbreak of the war created an urgent need for hospital beds, and Reading’s workhouse became Reading's no. 1 War Hospital. Nos. 2 to no. 6 section hospitals were located at local schools and the Royal Berkshire Hospital[1]. A war hospital depot was also opened in Reading, producing specialised equipment such as artificial limbs.

In total over 39,000 people were treated in Reading during the war.

Inscribed stone plaque from the 16 Duke Street premises of the Reading War Hospital Depot, about 1919 (museum no. 1997.72.97)

The 1918 pandemic in Reading

Despite the large numbers of soldiers from the European frontline, it seems that Reading escaped the worse of the 1918 pandemic. However, there were still large numbers of infections and deaths in the Reading area.

On the 26 October 1918 the Reading Observer reported:

‘The Influenza bacillus[2] which has been ravaging all over the continent, has undoubtedly arrived at Reading and is having its trail of death and illness in various parts of the town… our representative called at the Royal Berkshire Hospital… and was informed by one of the house physicians that several deaths had occurred there. The doctor stated that the outbreak was of very virulent nature and the deaths were mostly caused by pneumonia following influenza’.

Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading in about 1920 (museum no. 1976.36.8)

School closures and queues at doctor's surgeries

At first, the Reading Education Committee had to close two schools: Christchurch and St. Laurence's Schools. Only 247 children were present out of a total of 534 at Christchurch, and 111 of 193 at St. Laurence's. Many members of teaching staff were also absent.

A few days later, the Committee had no choice but to close all its schools, as up to 4,000 children had already been reported as absent. The Schools Medical Officer warned children not to go into cinemas and other places of amusement and advised them to keep in the outside in the open air as much as possible. If they should feel unwell, they were told to go home to bed at once.

By the 2 November 1918, the Reading Mercury recorded that ‘Reading has been spared the worst visitation of the influenza epidemic’. However, there were still a very large number of cases, and in several instances, complications leading to deaths. The Mercury reported: ‘The novel sight of a queue at a doctor’s establishment was seen in King’s Road on Wednesday morning’. While deaths were reported among the large numbers of military in Reading, due to the War Hospital, and all places of entertainment were placed out-of-bounds to soldiers.

The Observer reported a considerable proportion of day-boys and boarders at Reading School were down with the disease, while all boys at the Bluecoat School were told not to travel inside trams.

Christchurch School - Boys at Handwork, 1934 (museum no. 2016.64.7)

Armistice on 11 November 1918

Unlike the current COVID pandemic, there were few mandatory restrictions, and measures varied greatly between local authorities. Britain’s chief medical officer of health, Sir Arthur Newsholme, had issued a range of recommended measures to slow influenza, including isolating the sick from the healthy, school and cinema closures, oral disinfection (gargling with antiseptics), and warnings against large 'aggregations of people'.

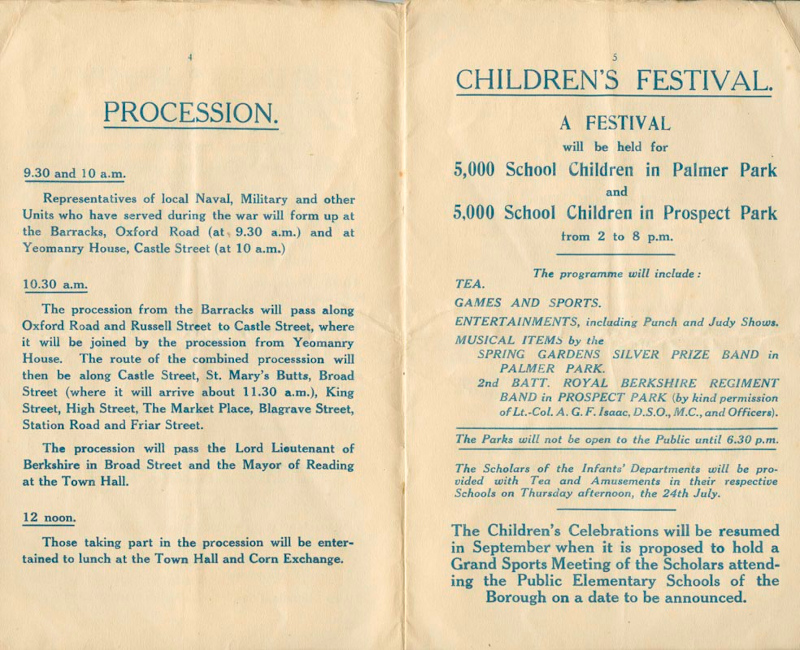

There were many reasons why measures were not systematically introduced, including the continued demands of the war effort and uncertainty among the medical profession about the nature of the pandemic. Many of the pandemic's attributes didn't confirm with what was then known of influenza: who it affected the most, the nature and severity of symptoms, and how it caused loss of life. At the same time, the public saw influenza as a mild illness and weren’t unduly worried. This can be seen in the public reaction to the armistice on 11 November 1918. After four years of war, people ignored health advice and gathered together in towns and villages across the country. The Reading Observer described ’seething masses of humanity’ in the Market Place, Broad Street, Friar Street, Oxford Road, Duke Street, and St. Mary's Butts.

The death of Arthur Sawyer

Throughout the autumn, local newspapers reported influenza deaths in Reading. On 19 October 1918, the Reading Mercury recorded the death of one of their own journalists, Mr. Arthur Sawyer. The Mercury reported that the late Mr Sawyer:

‘left a gap which it is almost impossible fill in local journalism, owing to his intimate knowledge of the locality, with which was joined a keen sense of the value of news. The late Mr. Sawyer took the deepest interest in the fund raised by this paper on behalf of the Reading War Hospitals Supplies Depot. He threw himself into the effort of raising money for this excellent object with the greatest devotion. He also had large share in the organisation of collections. Deep sympathy is felt with the widow and little boy, and also with the deceased gentleman’s mother'.

By 25 November 1918, the Reading Health Committee’s Medical Officer, Dr Ashby, was stating that the pandemic in the borough was abating. He also reported that in the previous week there had been 24 deaths from influenza (including five military cases), seven from bronchitis, and 12 from pneumonia (including one military case).

Bovril shortages and the return to peace

Reports of shortages were restricted to Bovril! This was probably because the nation was already subject to food controls due to the war. On 7 December, the Reading Mercury reported on an apology for the shortage of Bovril from its makers:

‘In View of the immense value of Bovril during an Influenza epidemic, the proprietors of Bovril are making every effort to meet the demand. The shortage of bottles is seriously hampering the endeavours to meet demand'.

Increases in flu and pneumonia were seen again in March 1919, and Reading’s Medical Officer of Health said:

'The golden rule is to keep fit, and avoid infection as much as possible… It is not always possible to avoid infection, but the risks can be lessened by - (a) healthy living; (b) working and sleeping in well-ventilated rooms; (c) avoiding crowded gatherings and close, ill-ventilated rooms; (d) wearing warmer clothing; (e) gargling the throat and washing out the nostrils; (f) by wearing a mask and glasses when nursing or in attendance on a person suffering'.

Flu cases did not return to the high levels of the autumn, and life returned to normal, seeing national peace celebrations for the end of the Great War in July 1919.

Official Programme of Ceremonies and Festivities for national rejoicing of peace in Reading, 19 July 1919 (museum no. 1987.21.2)

Footnotes

[1] Reading War Hospital was made up of No. 1 War Hospital – Reading Workhouse (later Battle Hospital), No. 2 War Hospital – Battle School, No. 3 War Hospital -Wilson School, No. 4 War Hospital – Redlands School, No. 5 War Hospital – Katesgrove and Central Schools, and No. 6 War Hospital – Royal Berkshire Hospital (military wards only). A further 36 auxiliary hospitals were established (not all operated concurrently) in large private house, public halls and District Hospitals across Reading and Berkshire that supported the main War Hospital. Convalescent homes were also established (including Dunedin in Reading which is still an independent hospital). References - Margaret Railton and Marshall Barr (1989) The Royal Berkshire Hospital 1839-1989, The Royal Berkshire Hospital; Margaret Railton and Marshall Barr (2005) Battle Workhouse and Hospital 1867-2005, Berkshire Medical Heritage Centre.

[2] At the time Influenza was thought to be a bacterium not a virus.