Room to Let: No Coloured Men

It was rough the first few years because it was hard to find rooms. There were rooms that were vacant but you would see signs that said ‘No Blacks’, ‘No Coloureds’, ‘No Irish’. Or you might see ‘English Only’.

- Roy Campbell, oral history

The arrival of black West Indians in the UK was seen as a “threat” to British society by many of the white population. This resulted in racial discrimination against the new migrants who were considered unwelcome, as evidenced in various signs at establishments stating “West Indians not welcome, above all, not indoors,” or “no coloureds”.

There was a housing shortage in Britain, and West Indians found it hard to find accommodation, a difficulty compounded by landlords refusing in many cases to rent to black tenants. As a result, housing offered to West Indian migrants was usually substandard, poorly located overcrowded and often lacking in basic facilities. Black West Indians were denied the ability to apply for Council housing and were met with resistance on the part of white landlords who often refused to let or sub-let properties to black tenants. In some instances, West Indians were met openly with signs which stated "if you are black you need not apply for the housing vacancy" as well as situations whereby when you arrived to inquire about a vacancy, and the landlord realised you were black, the vacancy no longer existed.

West Indians settled in neighbourhoods where they could find accommodation, which they had to share with others. Some of the migrants who arrived were not accustomed to these types of living conditions. It was very different from home, and not at all what they had imagined. To combat the discrimination they faced, many West Indians created better accommodations for themselves by sharing a whole house with other West Indians. This was a new experience for some who were not accustomed to having just a room in a house as opposed to having their own house. But they soon began to create independent micro-neighbourhoods, which existed within the larger white neighbourhoods. In time, they began to buy properties which they could then rent out to other Caribbean people. It was, however, often difficult for West Indians to raise mortgages, so they raised the funds through ‘meeting turns’ or ‘partners’.

Watch My Life as an Immigrant in 1960s Britain - #YourStoryOurHistory

No Scared of a Little Hard Work

Gilbert, come, you no scared of a little hard work. I can help you.

- Small Island, Andrea Levy

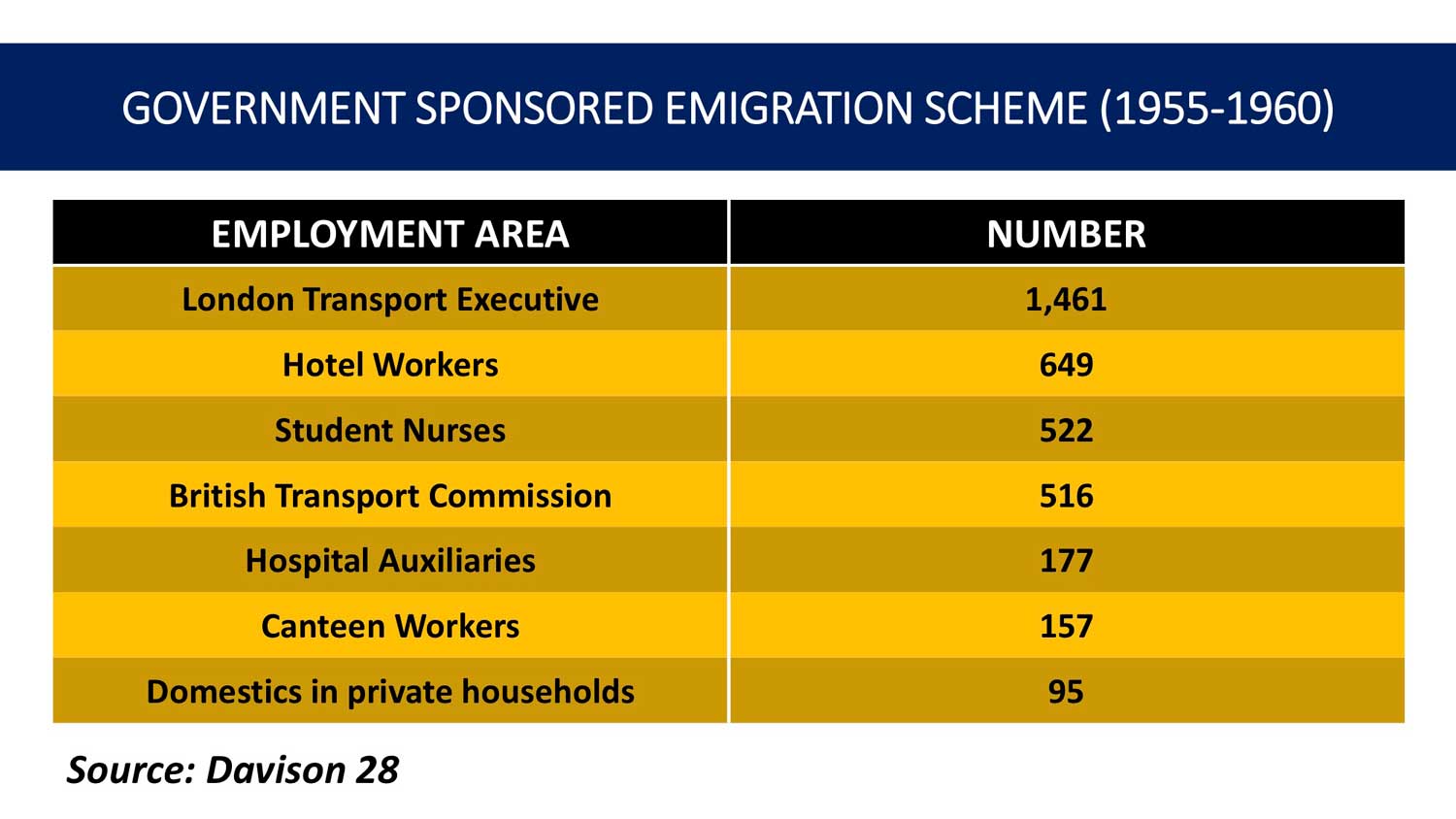

The British government had initially hoped that European immigrants would fill the labour shortfall in the UK after the war. This did not happen and the labour shortage was exacerbated by many white Britons opting to migrate to the “new” Commonwealth countries of Australia and New Zealand. It was only reluctantly, and in the early 1950s, that the British government turned to “coloured colonial labour” for assistance and some employers such as London Transport, the National Health Service, or the hospitality sector actively recruited from within the Caribbean.

Courtesy Dr. Henderson Carter

Many of the West Indian migrants were skilled and professional workers such as carpenters, motor mechanics, dressmakers, teachers, and engineers. Few were employed in those capacities and had to take on work in factories and on building sites, in hotels and restaurants such as the Lyons Corner Houses, or in transport. Many women were recruited by the National Health Service to train as nurses. Many West Indians, however, found themselves having to take work as porters and street cleaners.

The migrants took on positions that British citizens themselves often refused to fill, and found it necessary to supplement the wages they earned at their regular jobs with additional work, utilizing skills that they would have brought with them from home. This additionally allowed them the opportunity to foster a community spirit in their neighbourhoods.

The working conditions that West Indians experienced were no better than the housing conditions, as they often experienced racism and discrimination in the work place, in securing suitable employment, or in promotion. They were treated differently to their white counterparts when applying for, or carrying out similar jobs. For example, some whites refused to touch the hands of coloured conductors when giving them bus fare, instead opting to place it on the seat next to them.

Remittance

When I arrived in England, my thinking was that I would be away no more than five years. I had a goal of saving a certain amount of money then coming back to Barbados and getting a little home.

- Roy Campbell, oral history

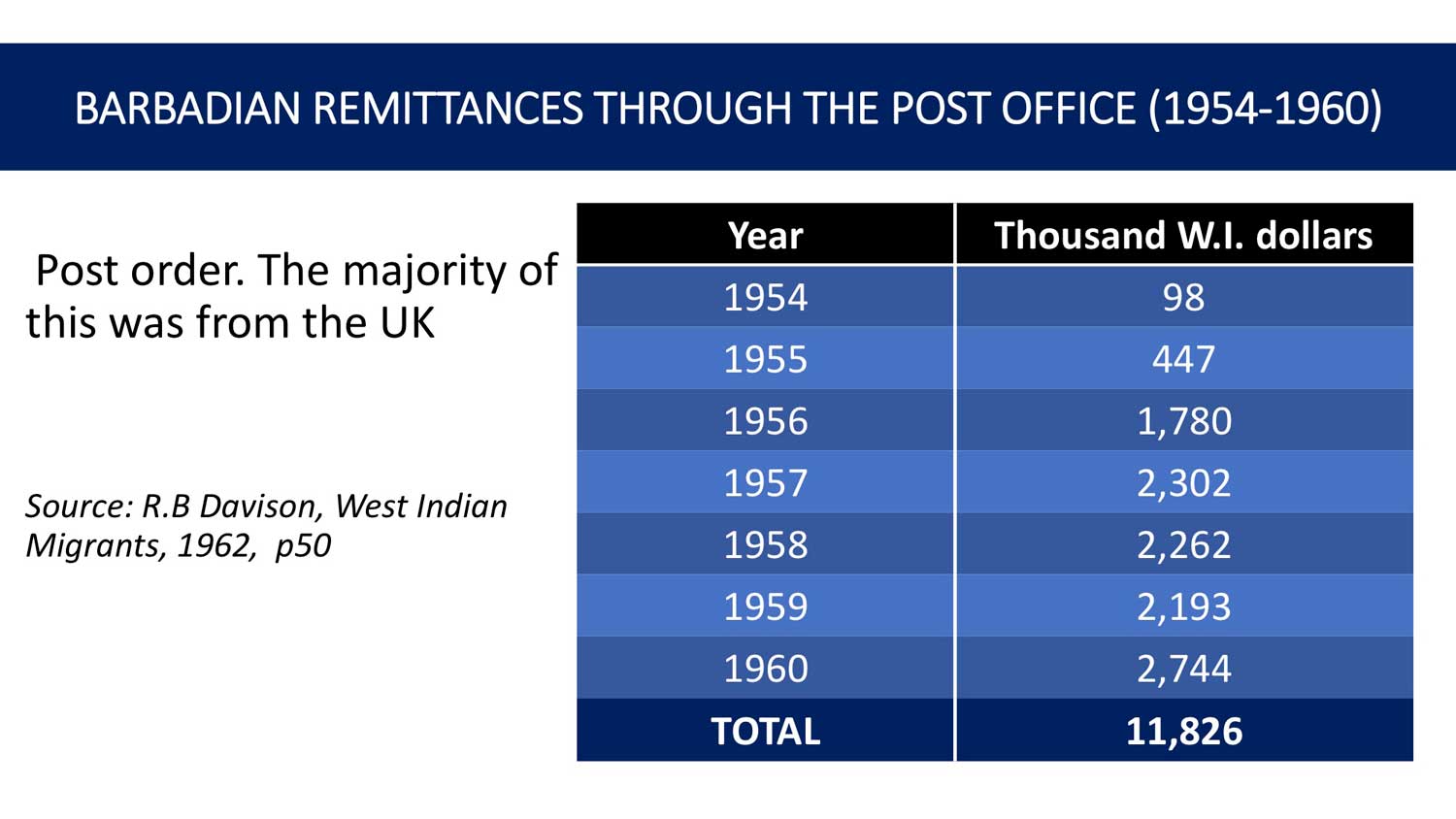

West Indians voluntarily remitted money back home. It was expected that any individual who went to the UK in search of a better life was would send home money to improve the lives of those they left behind at home, and to support family members. Repatriation, or remittances as it is also known, was the way in which migration helped to improve the economic conditions and family life back home.

Remittances were, and continue to be, a major source of foreign exchange earnings for Caribbean governments.

Courtesy Dr. Henderson Carter

“Grapevines” in a Lovely Miserable City

This is a lonely, miserable city, if it was that we didn’t get together now and then to talk about things back home, we would suffer like hell.

- The Lonely Londoners, Samuel Selvon

One way to deal with the discrimination and racism experienced in the UK, was for West Indians to build their own social networks, or adapt existing networks to their advantage. Some of these networks started out of kinship or family relationships, where siblings and cousins came together to support each other throughout the experience. Other networks were built on neighbourhoods and friendships which originated from home in the Caribbean.

For example, friends of a family often lodged new arrivals, not just looking after them, but showing them around and helping them get settled. In other cases, merely the recognition of someone of West Indian descent was enough to assure kinship among them, and an outpouring of support to assist them in whatever way needed.

As such, individuals made room in their homes and their lives to become new “families” with similar support and relationships to those in the Caribbean. These networks or “grapevines” were an adaptive response to the difficult situations and conditions that the migrants faced and helped them also find available jobs and become close knit communities in the process.

They held parties, dances and social gatherings. They also started local “meeting turns” or “partners” (informal savings groups) which they used, for instance, to raise the funds to buy property. They created church communities, Saturday schools, island communities, sporting associations and welfare organisations. They organised politically, and, with other Caribbean people, were in the vanguard in the pushback against racial discrimination. This was partly, for example, through the efforts of activists such as Claudia Jones, and after 1965, through organisations such as the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD), or the West Indian Standing Conference. They organised activities culturally, via the organisations like the West Indian Students Association and the Caribbean Artists Movement, from large scale events like Notting Hill Carnival – a direct response to the race riots of 1958 - to the establishment of bookshops, publishers, newspapers and journals.

Leave the Girls Alone at Work

I told them they had come to this country and that there were prejudices against them, and the quickest way to stir them up is to make advances to one of the girls.

- A.V Willmott, ‘An Employer’s Point of View’, Going to Britain?, 1961

Although some travelled alone, many of the migrants either left to join family or friends or were accompanied by family members. Those who did not already have personal relationships in Britain, set about forming their own.

Racism played a part in any romantic relationships that West Indian migrants sought to have with white British women.

Because of racism, interracial relationships were greatly feared, resented and seen by some white Britons as an abomination - for example any white woman who was believed to be in a relationship with a black man was likely to be considered morally “loose”, ridiculed, shunned by her community, and even threatened with bodily harm from strangers. Interracial couples and marriages were often not tolerated by the majority white population out of ignorance and prejudice and a fear that, perhaps, black masculinity (as an old racist trope) threatened white males and “soiled” their women.

However, despite discrimination in relationships as well as in housing and employment, large multiracial communities grew up in the inner cities of London, Bristol, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Reading and elsewhere. Brixton in South London in particular emerged as an early multi-racial community. This could have been due to the fact that original migrants from the “Windrush Generation” had been temporarily housed in an empty air-raid shelter in Clapham, and reported to the nearest Labour Exchange – in Brixton.

Nevertheless, white vigilante groups such as teddy boys, provoked by agitators such as the fascist Union Movement and the White Defence League, instilled fear in these communities. In 1958, white provocation led to riots in Notting Hill, in London, and in Nottingham and to the murder, the following year, of a young Antiguan, Kelso Cochrane.

One response, led by among others the Trinidadian Claudia Jones, was to organise a carnival to celebrate Caribbean culture in face of such hostility, and to assert a positive Caribbean presence. The Notting Hill Carnival is now the largest such carnival in Europe.

God and History Will Remember

Colour hatred and world prejudice are so strong today that everything done seems to aim at the subject of negroid peoples. Whatever restrictions imposed by Britain against people of goodwill in the Commonwealth in preference to the people who scalded Britain with incendiary bombs, when we shared in that defence, God and history will remember any restrictions British Government may impose on West Indians, particularly, Commonwealth immigration into Britain.

- Secret Telegram from the Colonial Administrator on behalf of the St. Vincent Government to the Secretary of State of the British Government, October 21st 1961

Early political responses by Caribbean leaders to the call for migration to the UK was generally positive, as political leadership largely recognised the potential economic gains of relieving pressures on the local market in the colonies and receiving valuable remittances from abroad.

However, there were increasing pressures in Great Britain to control immigration from the “new” Commonwealth, not only the Caribbean but also from the Indian subcontinent. This led to the Commonwealth Immigrants Acts of 1962 and 1968, designed to regulate the flow of migrants to Britain. Political leaders in the Caribbean then recognised that the open and free period of migration was being forced to a close. Increasingly overt racism was affecting British politics and legislation, the effects of which would have a negative impact on the region.

The West Indies Federation, under the leadership of Grantley Adams, therefore felt it necessary to take overt steps to engage and negotiate with British politicians as heads of Government. They also supported the efforts of politicians and activists in Britain against these new and increasingly racist policies which made the British citizenship of those who had entered Britain as British citizens, but who had been born in the West Indies, increasingly vulnerable.

“Everyone Had a Place.”

The war was fought so people might live amongst their own kind. Everyone had a place.

- A Small Island, Andrea Levy

For some migrants, relationships between them and migrants from other countries differed greatly. For instance, the experiences between Barbadian and Jamaican migrants was in some instances one of kinship and camaraderie where they recognised that they were both in a situation that was not working out as they would like and they adapted in ways that enabled them to have a better experience and reduce the hardships they had encountered. In other ways, however, the experiences were negative and there was animosity between the two cultures.

A Barbadian migrant to the UK recalled an instance where the "Jamaicans would tell Bajans (Barbadians) to go back to their small island and Bajans would have responded that their island is small so that they can hear the school bell while Jamaica is so big that Jamaicans could not hear the school bell and that is why they are so ignorant."

Another memory spoke to the cultural tensions between African students and their Caribbean counterparts, where "the Africans said to the Caribbean students that they are slaves," and the Caribbean students responded, "thank God we have come out of it [slavery] but you all are still in it”. These various experiences showed that not only did Caribbean migrants face discrimination from whites, but there was also a wide range of tensions amongst different heritages. The legacy of colonial peoples often pitted them against each other in their metropole.

London Transport Bus Conductors © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection