Migration before Windrush

You see me here on dis boat leavin' Trinidad. Well, 'tis simply because ah little tired. Ah sick, bored. Ah doan' care w'at ah do next, but ah can't stan' in Trinidad no more 'cause ah know w'at rum taste like, an' ah know w'at woman taste like, an' if you know dose two you know Trinidad.

- The Emigrants, George Lamming

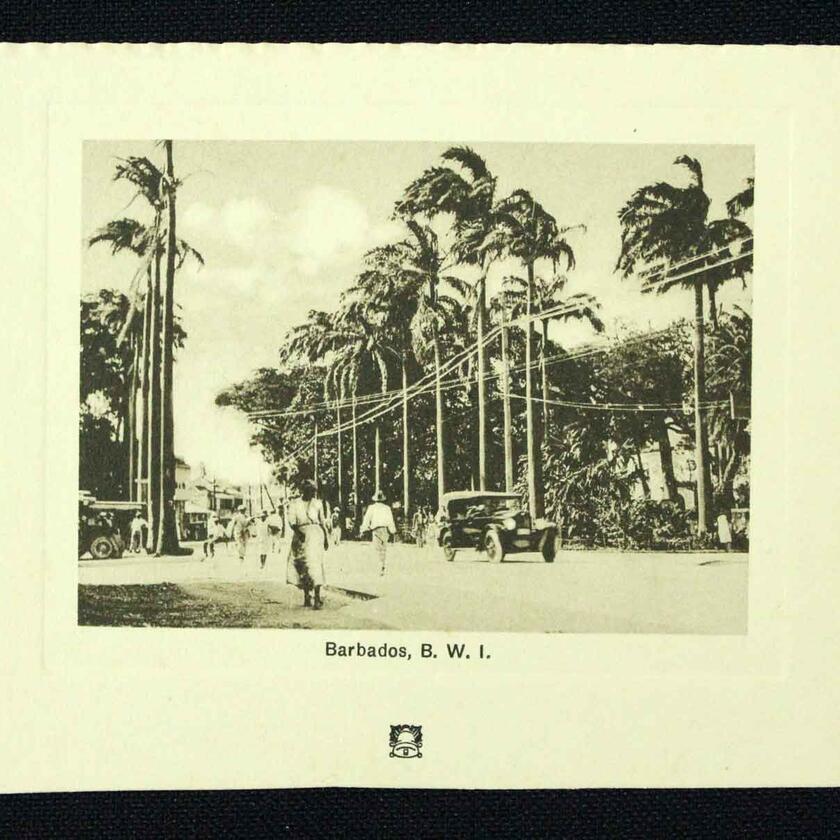

Prior to the mass migration to the UK following the end of World War II, Caribbean people had already developed patterns of migration, after Emancipation, to countries which provided the best opportunities for work. Migratory movements from the latter half of the 19th century and the early 20th century became the new norm as thousands of British West Indians migrated to destinations within the Caribbean, or to Central and South America and the United States.

From 1904, by far the largest migration was to Panama to work on building the Panama Canal. Some migrants remained in Panama, some returned home to their islands, and others re-migrated. Destinations included Honduras, labouring on banana plantations; Costa Rica and Guatemala, working in the coffee industry; Cuba and Dominica, working on sugar plantations; Venezuela, working in the goldfields and Brazil, on the railway. Others moved on to the United States.

In 1924, the USA passed the Immigration Act which severely restricted migration to that country. It was followed by exclusionary measures in the Hispanic Caribbean. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, also known as the MacArran-Walter Act, placed further curtailments on West Indians, which was one of the reasons that the migration flow was diverted to the United Kingdom.

Before the Second World War, there had been limited migration to the United Kingdom. This included seamen who settled in the UK, mainly in port cities, while others included students like Charles Duncan O’Neale and Harold Moody who settled for shorter periods. This period also saw the migration of radicals such as C L R James and Marcus Garvey, who ironically found the metropole less restrictive than the colonies.

Caribbean Family Life

My mother was very strict… and I thought… it might be a good idea, just to leave the country, because I couldn’t see my mother really letting go if I’d stayed at home in Barbados.

- “Euline”, in Narratives of Exile and Return by Mary Chamberlain

Family is important in Caribbean social life and generally consists of a large/extended family. Families usually resided in rural and semi-rural communities or country villages, which fostered their sense of community spirit and extended familial ties.

Parents tended to be very strict with their children in terms of what they were allowed to do, and most families instilled in their children the importance of an education in order to help improve their standard of living. Children were brought up to help and contribute to the upkeep of family life, by assisting with their younger siblings, helping with household or garden chores and, later, contributing financially. Grandmothers played an important role in caring for children while their parents worked and most families were inclusive in their membership and close knit.

For most families, a strong religious background was the cornerstone of social life in the Caribbean and religion formed a focal point for the community. Religion in the colonies varied from Protestant, Catholic, Pentecostal and various syncretic Christian denominations established during the colonisation period – to Hinduism and Islam as a result of Post-Emancipation indentureship from the Indian sub-continent. Nevertheless, Christianity was the most prevalent. As religion was such a strong feature in West Indian life, it formed a driving force in any life changing decisions they made.

Chattel houses in Barbados in the 1930s - BMHS Collection

Educated for Escape

From the beginning they had been educated for escape.

- Water with Berries, George Lamming

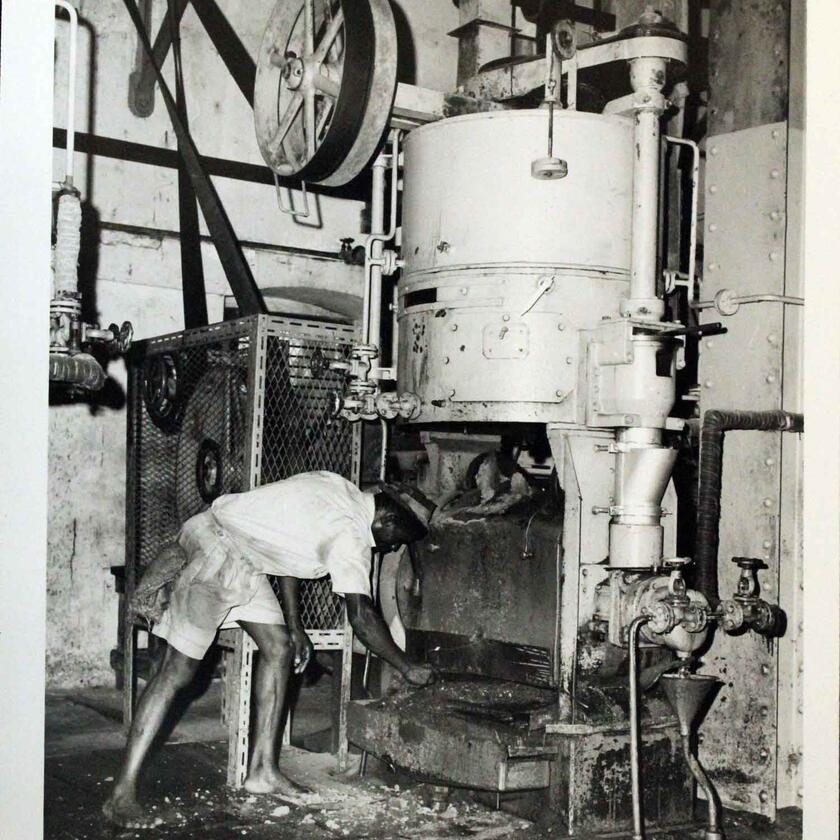

When full Emancipation was achieved in 1838, the ability to find work away from the plantation system proved difficult for many. A high premium was put on education by the former slaves so that by the mid-twentieth century, most of the migrants to Britain were educated. Some achieved a Standard 4 education (equivalent today to a school leaving certificate), however, the majority of them only finished elementary school. A smaller number completed some form of secondary education, and a very limited number achieved of some tertiary level studies. Some migrants left in order to improve their education, but many, including the highly skilled and educated migrants, experienced de-skilling.

The limited educational background of many individuals determined their status as well as their prospects for employment in Britain. Wages were low and those who had trade skills such as carpentry, masonry, building, tailoring and dressmaking, managed to utilise them to help supplement their income alongside their regular occupations. These factors determined that while some could aspire to the middle-income strata of society, most West Indian workers would become part of the British working-class.

Big-Time Job

And every month they leave the right way, paying a passage in search of what: a better break. That’s what the others say. Every man wants a better break.

- The Emigrants, George Lamming

People from the Caribbean made the choice to migrate to the UK for a variety of reasons, including:

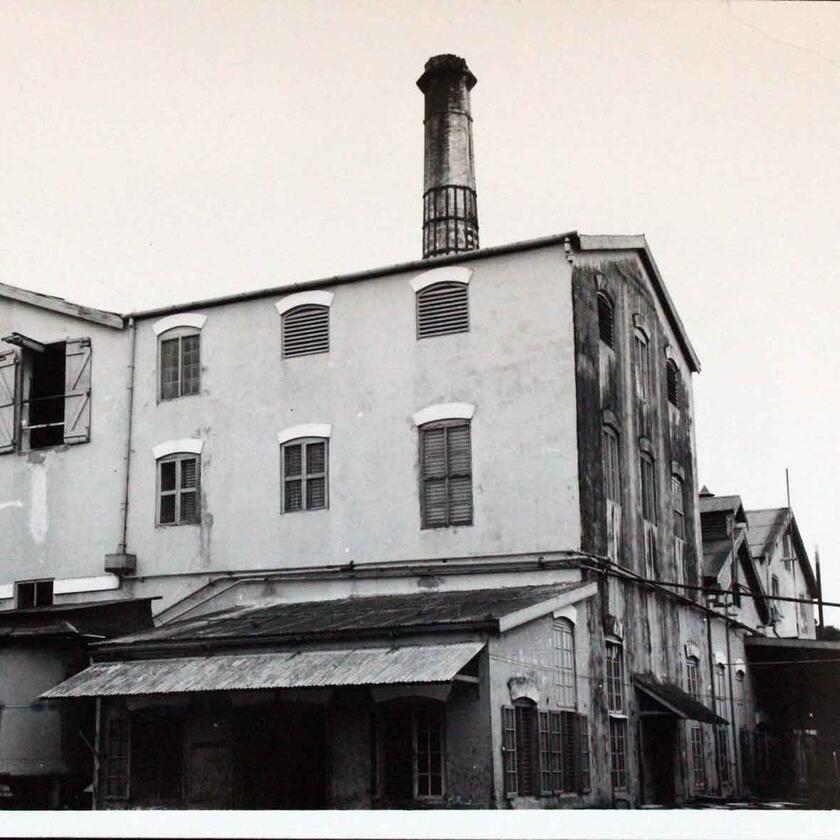

- Unemployment and underemployment in the Caribbean since Emancipation

- Service at the end of World War II and the need for workers to help with the post-war reconstruction of Britain

- Governments schemes in the Caribbean to sponsor workers in “state-aided migration”

- UK based employers offering work and training

- Adventure and travel

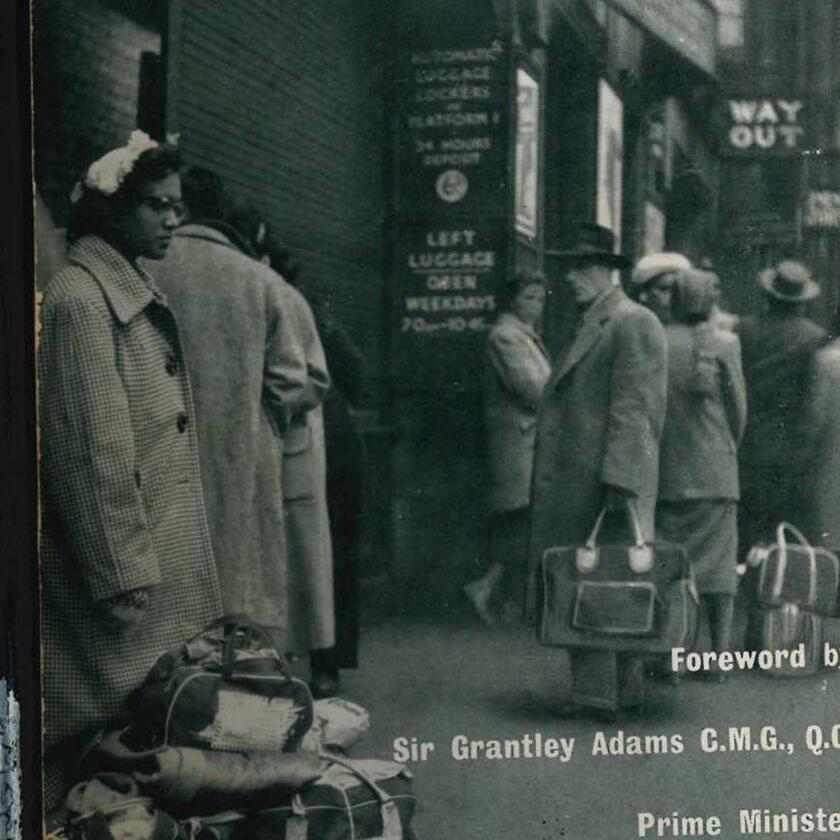

Letters written by those who had migrated contained missives of encouragement to those left behind to come and enjoy the good life in the UK. Further encouragement came in the form of local press reports and news from returning emigrants. Recruiting agencies that advertised opportunities for improved wages and conditions also served to help fuel the migration fever.

Newspaper Advert for Passengers to Sail on Empire Windrush

The hope of higher wages to help improve the lives of those family members left behind - and the potential for greater educational opportunities - also proved to be a great incentive to migrate.

Made in England

It had written on it the name of the company, the year the company was established, and the words “Made in England.”

- On Seeing England for the First Time, Jamaica Kincaid

Most Caribbean people knew about the UK through the newspapers and various radio programmes that were broadcast throughout the British West Indies; these ranged from news and sports, to culture and current UK affairs. In addition, they learned about the notion of a "Mother Country" through the education and social system in the British West Indies, which mirrored that in England. This included adopting the national flag, anthem, Christian religion, cricket, literature, national holidays - including celebrating Empire Day - and revering the Royal Family. These first impressions, indoctrinated at a young age, gave an idealistic view of the UK so that many migrants thought they would be going to a fairy-tale land where all was well, with none of the problems that existed at home in the colonies. The "Mother Country" was perceived as a welcoming "home" of a family of nations, which had extended an invitation to come. The 1948 Nationality Act conferred the status of “Citizen of the United Kingdom and its Colonies” on the migrants, giving them the right to enter freely. Migrants believed they were British citizens. This cultural heritage and legal status distinguished Britain from earlier migrant destinations.