Rivers of Blood

Maggi Tatcha on di go

wid a racist show

but a she haffi go

kaw,

rite now,

African

Asian

West Indian

an´ Black British

stan firm inna Inglan

inna disya time yah.

- “It Dread Inna Inglan”, on Dread Beat an' Blood by Linton Kwesi Johnson (Heartbeat Records)

Enoch Powell and Margaret Thatcher were two of the most notable figures in British politics when it came to Commonwealth immigrants in the UK. They are both known for their stances on immigration in the UK and who they considered constituted a British citizen.

As Health Minister during 1960 to 1963 Enoch Powell invited West Indian nurses to come and work for the National Health Service in Britain. By 1968, however, he delivered his famous "Rivers of Blood" speech, criticising mass immigration and the proposed 1968 Race Relations Bill which sought to end discrimination based on grounds of ethnicity and national origins. This also coincided with the 1968 Commonwealth Immigration Act which sought to restrict further the entry of citizens from Commonwealth countries.

Powell, in particular, advocated the halting or reversal of post-war immigration from the colonies failing which he predicted he could see “like the Roman...the River Tiber foaming with much blood”, caused by the violence that immigration would bring. English people it was feared, would awaken one morning to a country that was no longer theirs.

The fight against Commonwealth citizen immigration to the UK culminated with the 1971 Immigration Act which saw even more restrictions placed on Commonwealth citizens. This was followed by the 1981 British Nationality Act passed by Margaret Thatcher's government, which re-defined British citizenship. Citizenship was no longer based on imperial ties to Britain, which had extended to all citizens of the Commonwealth. Instead, only those born in Britain, or the descendants of those born in Britain, could claim to be British. Powell's inflammatory anti-immigration rhetoric paved the way for Margaret Thatcher to continue the anti-immigration battle. Thatcher campaigned on a platform which queried how many immigrants were too many, while she staunchly tried to identify how a British citizen should be defined.

It would have a lasting impact on many immigrants and their descendants who would one day awaken to find themselves abandoned and without a country to call home.

Watch Uk: Demonstrations, For And Against Mr. Enoch Powell 1968

Barbara Grey at a Training centre for black women in 1974 - Photo Courtesy Neil Kenlock

If a Fellar Too Black...

If a fellar too black, Bart not companying him much, and he don’t like to be found in the company of the boys, he always have an embarrass air when he with them in public, he does look around as much as to say: ‘I here with these boys, but I not one of them, look at the colour of my skin.’

- The Lonely Londoners, Samuel Selvon

Many West Indians believed that migrating to the UK would provide them with better opportunities to improve their social status. What they did not expect was that it may also change who they were socially and culturally. West Indians with lighter skin were surprised to experience the same treatment as the other darker migrants. For these persons this was quite a shock because they now had to struggle and compete to secure jobs, housing and other amenities whereas back home they often enjoyed a privileged status within society. Some tried to separate themselves from the darker skin immigrants, sometimes going so far as to directly ignore their fellow countrymen when they perceived that their association might draw unwanted attention to themselves.

Syd Shelton, Brixton 1977

Some migrants learned to modify their cultural upbringing because of the way the British people reacted and treated them. Cultural practices instilled from home such as being “mannerly” and greeting people with whom you came into contact were ignored by the British.

One migrant man recalled that when he entered the doctor’s waiting room and greeted all present no one replied. In another instance a female migrant recalled that while her white workmates were friendly at work, they would not acknowledge her outside the work environment.

As a result, there was little initial interaction between the West Indian and the white British communities. In the educational system, migrant children were treated differently. Teachers often did not recognise ability, or encourage it, and assumed that West Indian children could not compete with white British children educated in the UK. This led to supplemental schooling being offered within Caribbean communities in order to help these children to progress. Even now, Caribbean heritage children are still discriminated against in schools, and at university entrance.

Many Caribbean heritage families began to espouse a positive Caribbean identity, nurturing and imparting Caribbean culture – cuisine, music, literature, history, identity – to their children and grandchildren.

You are the stranger © BBC copyright content reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

Not Exactly What You Expected

You hear so much about England and Europe, but when you go there it is not exactly what you expected.

- Roy Campbell, oral history

There are three main areas that stand out when considering West Indian attitudes towards migration and living in Britain: the intended length of stay, the conditions they encountered and the reality of the UK/”Mother Country”.

Length of stay played the biggest and most important role in how West Indians viewed their experiences in Britain. Most migrants travelled to the UK with the mind-set that it would be short-term, for a period of 3-5 years. Given this, many felt that any inconveniences or difficulties could be tolerated because they were temporary. This attitude laid the foundation for almost all other issues that migrants encountered during their time in the UK.

Their belief in the temporary nature of their stay allowed people to overlook the difficulties they faced while trying to find jobs and housing, even though frustrated and appalled by the conditions and attitudes toward them by the locals. Migrants accepted all manner of challenges thrown at them because they believed that it was only for a time that they needed to deal with these negative aspects of their migration experience.

Even the cold, bleak, sombre and stark difference from all the stories that were told by friends or family who encouraged them to migrate, as well as the pictures they conjured up when listening to the various programmes and news about the UK, were not enough to dissuade migrants for them to want to return home. There was a strong belief that almost anything could be tolerated as it was not going to be for an extended period.

Vegetable Stall © BBC copyright content reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

Never Felt I Belonged Here

I never felt I belonged here. It is not my home. Jamaica is my home, it’s in my blood.

- The Windrush Legacy, Sarah Thompson

The concept of home had two different meanings for Caribbean migrants.

For some it was a symbol, a place of belonging, which also helped to play a role in the construction of their identities. Home served as a fantasy shaped by the teaching system within the colonies, which made the UK seem like “home”. In this respect, the concept of home was used as a mechanism for social control and imperial loyalty.

The Caribbean, on the other hand, also served as the symbol of home. It was referred to as home by all who had been born there, and would always be home, even to those who were born in the UK. The Caribbean as the symbol of home was an inherited memory for those born in the UK, something that they experienced as descendants of those who migrated from the British colonies. It also served as a symbol of resilience to remind them of where they had come from, what they endured and what they could possibly overcome.

The emotional need to maintain contact with home meant that West Indians would never forget where they came from, while the un-severable link with the "Mother Country" guaranteed that the colonies would always have some sense of loyalty to the UK. This made it inevitable that home would always have a dual meaning and that each place would have a different attraction to the migrants and citizens alike.

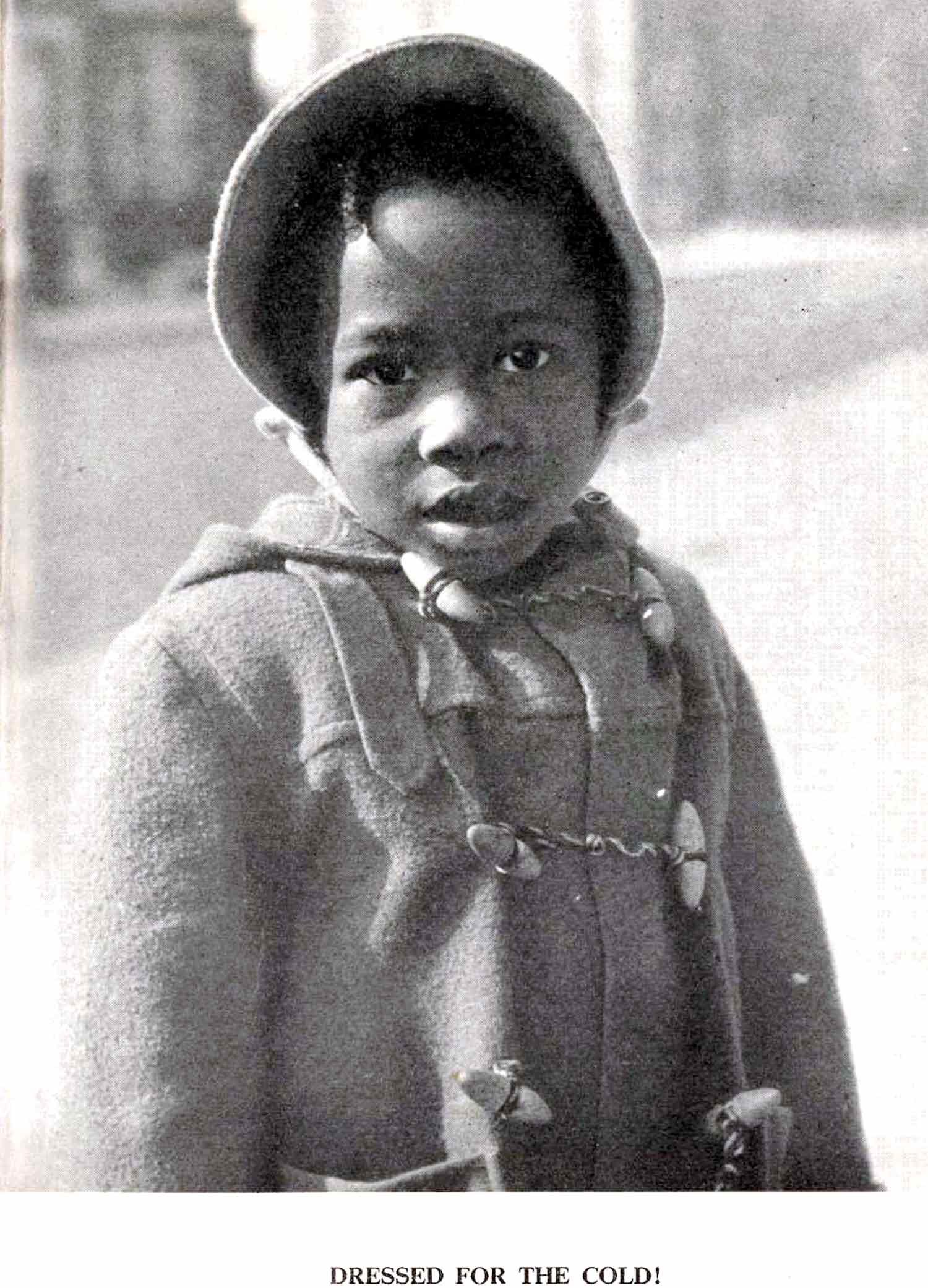

Dressed for the Cold! © BBC copyright content reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

Colonization in Reverse

Wat a joyful news, miss Mattie,

I feel like me heart gwine burs

Jamaica people colonizin

Englan in reverse- Colonization in Reverse, Louise Bennett Coverley

So many migrants could not have settled within the heart of the UK without making an impact on the society within which they lived. Despite the resistance to the visible difference in the colour of their skin, many cultural practices of Caribbean migrants have become norms within British society, and many have made distinctive contributions to British cultural, professional and social life.

Many migrants found British meals lacking in flavour after the highly seasoned food of the Caribbean and they introduced both produce and traditional dishes from their homelands. Supported by West Indians and other colonial peoples, cook shops sprung up in migrant neighbourhoods and Caribbean food became a part of British culture, particularly in the urban areas where they settled.

In addition, West Indians made themselves felt though the arts, sports and culture. Writers such as Samuel Selvon, V.S. Naipaul and George Lamming, or poets such as Louise Bennett, migrated and became published authors documenting the colonial experiences of black and brown people. Their work was heard in the Caribbean and, through the influential radio programme, Caribbean Voices broadcast by the BBC between 1943 and 1958, encouraging other West Indians to write distinctively Caribbean prose and poetry. Later, poets such as Linton Kwesi Johnson, or Caribbean-heritage novelists such as Andrea Levy, Kei Miller, Caryl Phillips, Zadie Smith or Bernadine Everisto, published or performed within urban cultural spaces.

Another significant contribution of Caribbean migration on British arts was through the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) started in 1966. Visual artists participating in this movement included Paul Dash, Cecil Baugh, Aubrey Williams and Althea McNish.

Furthermore, although British people did not necessarily embrace the migrants themselves, they readily embraced cultural influences from calypso and carnival, while supporting black players representing England in sporting events at the international level in cricket and football and participating wholeheartedly in the diverse collection of music, food and cultural life which became a part of the melting pot in London city life.

The Emigrants by George Lamming 1995

Carnival in Notting Hill

“…we got to do something to make this come alive …”

Russel Henderson, the Russ Henderson Steel Band

“Notting Hill carnival is our home”

Sadiq Khan (Mayor of London)

“Carnival is life for me”Kyra (a carnival goer)

- Notting Hill carnival 2018: Why the Caribbean origins of Europe's biggest street party are so important, Georgia Chambers, 24 August 2018

Notting Hill Carnival, Europe’s largest street festival, was a response to the brutal racial violence that existed in England in 1950s. It was also seen as a way to bring culturally mixed communities in the UK together. These racially and culturally diverse groups had an uneasy co-existence. A carnival was seen as a way of allowing these groups to appreciate cultural diversity and to find common ground whilst relieving the tensions caused by their living together.

Racial tensions across England were brought to a head in 1958 when the white nationalist teddy boys intervened in a domestic dispute between an interracial couple. The race riots of 1958, spanned the period August 31st to September 5th 1958 with Nottingham and London being the “hottest” spots.

At the time of the riots, many West Indians who had migrated to fill the post-World War II labour shortage in Britain lived in Notting Hill. Other residents in this community were members of the British working class, migrant Irish and European Jews. Notting Hill was considered to be one of London’s urban slums. Oswald Mosley’s fascist “Keep Britain White” campaign, which advocated the forced repatriation of West Indians and a ban on interracial marriages, heightened racial tensions. Exacerbating Moseley’s narrative was a down turn in England’s economy, fierce competition for jobs and a lack of opportunities for the poor.

After the riots, several people sought to counteract racial tensions through social activities. Trinidadian activist Claudia Jones, with support from Jamaican Prime Minister, Norman Manley, set up a fund to assist with paying the fines of black people who had been arrested during the 1958 riots. In addition, with support from both Manley and Trinidadian Prime Minister Eric Williams, she founded the West Indian Gazette, an Afro-Caribbean newspaper and the United Kingdom’s first major black paper.

Claudia Jones then went on to found the first indoor Caribbean carnival, in January 1959, committing herself to both the culture and political underpinning of Caribbean carnival. When she founded the event, erected by Eric Connor, a Trinidadian actor, folklorist and calypsonian, held in St Pancras Town Hall, it was televised by the BBC. Her creation of a ‘mas camp’ and her focus on community development to pursue carnival as a collective enterprise laid the foundation for what was to become an annual coming together of the West Indian populations in and around Notting Hill, prior to her death in 1964.

In 1964, community activist, Rhuane Laslett converted Jones’ carnival into an outdoor event in Notting Hill. Laslett’s more cosmopolitan carnival was marketed as a ‘Fayre’ similar to a traditional British fête. Laslett expanded Notting Hill’s Caribbean influence by involving persons like musician Russell “Russ” Henderson who is responsible for transforming Notting Hill Carnival into today’s Caribbean-flavoured street festival, complete with ‘mas’. Sterling Betancourt, a pioneer of steelpan to Europe, was one of those responsible for incorporating pan into Notting Hill Carnival.

The Carnival’s impact has moved well beyond the introduction and integration of West Indian culture into Britain. London's West Indian community embraced carnival as an important source of celebration and cultural identity in the face of racist intimidation in Britain. During its early years Notting Hill Carnival has encouraged many a Briton to visit the Caribbean to experience the real thing first hand. In addition, the Carnival has led to a demand for West Indian goods and services (including music, food and fashion) which contributes to West Indian economies.

Cricket Lovely Cricket

With those two little pals of mine, Ramadhin and Valentine

…

The bowling was superfine, Ramadhin and Valentine

…

West Indies voices all blended.

Hats went in the air.

They jumped and shouted without fear;

So at Lord's was the scenery

Bound to go down in history.- Test Match aka Victory Calypso, Lord Beginner/Lord Kitchener

Perhaps the biggest sporting and indeed cultural impact made by the West Indians in Britain has been felt through their dominance in cricket, which was an Empire-wide obsession during the “Windrush Generation” era.

C.L.R James articulated, most significantly, that “West Indian Independence and national consciousness would not be shaped until they had beaten England at home at a game they had invented.” West Indian cricketers’ names – Sobers, Walcott, Weekes, Worrell, Gibbs, Richards, Holding, Lloyd, Roberts, in a seemingly endless list - became household words as the West Indies achieved worldwide cricketing dominance and the “calypso cricketers” invaded English club cricket where they continued to dominate.

The impact of the historic test victory at Lords in 1950 reverberated beyond England and around the West Indies, with public holidays in Jamaica and Barbados, and is still remembered every time the West Indies is victorious over England, even today. Reports in the papers at the time noted not just the impact of the crushing defeat at Lords but also the effects of the West Indian spectators at Lords as reflective of a new sporting culture and indeed a changing social culture in Britain itself.

As noted by The Times, cricket was now accompanied by “a loud commentary on every ball”, and the Gleaner, “bottles of rum were produced like magic”. John Arlott, a noted sporting journalist of the time observed “above all, the West Indian supporters created an atmosphere of joy such as Lords had never known before”.

Cricket brought nations together as evidenced by the many West Indian flags draped over the front of the Kingsley Hotel where the team was staying. Though they excelled at many other sports (football, boxing and rugby for example), cricket gave a sense of national pride, a purpose and an immersion in cultures that was seen otherwise only with the development of the Notting Hill carnival.

West Indian cricket influence was reflected also at the local levels where West Indians played league cricket and formed their own clubs, imbuing them with a character and play which was more “attacking” than standard English cricket at that time. So prevalent were West Indians in English cricketing that within forty years of the Windrush landing, Barbadian born Roland Butcher became the first black player to represent England, making his test debut at Bridgetown in 1980-81 commemorated by the local paper headline "Our boy, their bat!" (http://www.espncricinfo.com/england/content/player/9329.html)