With a length of more than seventy metres, both the original Bayeux Tapestry and our Victorian replica contain astonishing amounts of detail, including finely stitched depictions of:

- 626 human figures

- 190 horses

- 35 dogs

- 506 birds and animals

- 33 buildings

- 37 ships

- 37 trees or groups of trees

- and 57 Latin inscriptions

Below, learn about some of the most important figures to appear in the Tapestry, and find out the role they played in the events before, during, and after the Norman conquest of England.

You can also read about the women who made Reading's Victorian replica.

Edward the Confessor

Edward was King of England at the beginning of the Bayeux Tapestry. His death, and the matter of his succession, set the scene for the conflict between Harold and William, which culminated in the Battle of Hastings.

King of England, 1042-1066

Edward the Confessor was the son of the Saxon King Ethelred (the Unready) and Emma, sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy. Emma later married Cnut, King of Denmark. Cnut became King of England and Edward went to live in exile in Normandy.

When Cnut died in 1042, his son Harthacnut was made King of England. But Harthacnut died without leaving an heir, so Edward became King in 1042 and was crowned at Winchester in 1043. He ruled with the help of powerful Saxon earls, and married Edith, daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex. Edward invited many of his Norman friends to come to England. He gave them important jobs and land, and ordered the building of Westminster Abbey.

Because Edward had no children, he had to choose someone to succeed him. There were many claimants to the throne. One was Harold, Earl of Wessex, Edward's brother-in-law. Another was Harold Hardrada, King of Norway. A third was William, Duke of Normandy. The strongest claim was from Edgar Aetheling, Edward's great-nephew who had been raised by Edward since 1057 when he was four-years-old.

The Normans contended that Edward had promised the throne to William, but Harold Godwinson was chosen as Edward's successor when Edward died in January 1066.

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson, a revered warrior and the Earl of Wessex, here becoming King of England after Edward's death in 1066.

King of England, Jan - Oct 1066

Harold had no hereditary claim on the throne, and was not of royal birth. He was the son of Godwin, who in his time was the most powerful of the Saxon earls. Harold's sister, Emma, was married to Edward the Confessor and had at least five brothers. Harold was known as a revered warrior, and the tapestry shows Harold fighting alongside William against Conan, the Duke of Brittany, and Harold swearing upon holy relics, possibly in support of William's claim to the English throne.

When Edward died, Harold was chosen to be King of England by the leading Saxon noblemen, and he accepted their offer.

Right away, Harold ran into problems. Harald Hardrada, the King of Norway, invaded England to pursue his claim on the English throne, and was accompanied by Harold's own brother, Tostig. Both Hardrada and Tostig were killed by Harold's army at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, near York.

At the same time, William of Normandy brought his army to England to dispute Harold's succession and vie for the crown of England for himself. Harold marched from Stamford Bridge to London, and then onto Hastings where William's army waited. The English and Norman armies both fought bravely, but Harold was killed, alongside his brothers Gyrth and Leofwine. The tapestry tells us 'here King Harold has been killed', struck down by the sword of a mounted Norman knight.

After the Battle of Hastings, William had an abbey built on the place where the battle had been fought: Battle Abbey. The abbey's high altar is supposed to mark the spot where Harold was killed.

William of Normandy

Before the events of 1066, William was the Duke of Normandy. However, he was a claimant to the English throne, and after the death of Edward the Confessor, he invaded England to seize the crown, supported by the Pope.

King of England, 1066-1087

William's father was Duke Robert of Normandy, and his mother was Herleva, a tanner's daughter. Duke Robert's great-great-grandfather was Rollo, a Viking who invaded France in 911. Although he was illegitimate, William became Duke of Normandy when he was only seven years old. His father died whilst on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. William's mother later married the Viscount of Conteville and had two more sons: William's half-brothers, Odo and Robert.

William was a strong leader and wanted to become King of England. William led his army at the Battle of Hastings where Harold was killed and his army defeated. William then set about the conquest of England; he granted Norman barons pieces of land all over the country. In return, these barons supported him in war and administered regions of England on the King's behalf.

During his reign, William ordered the collection of information about the people in Britain and how much property they owned. This information was recorded in the Domesday Book. William died in 1087 after being injured whilst fighting in France. William's youngest son Henry became king of England in 1100, and founded Reading Abbey in 1121.

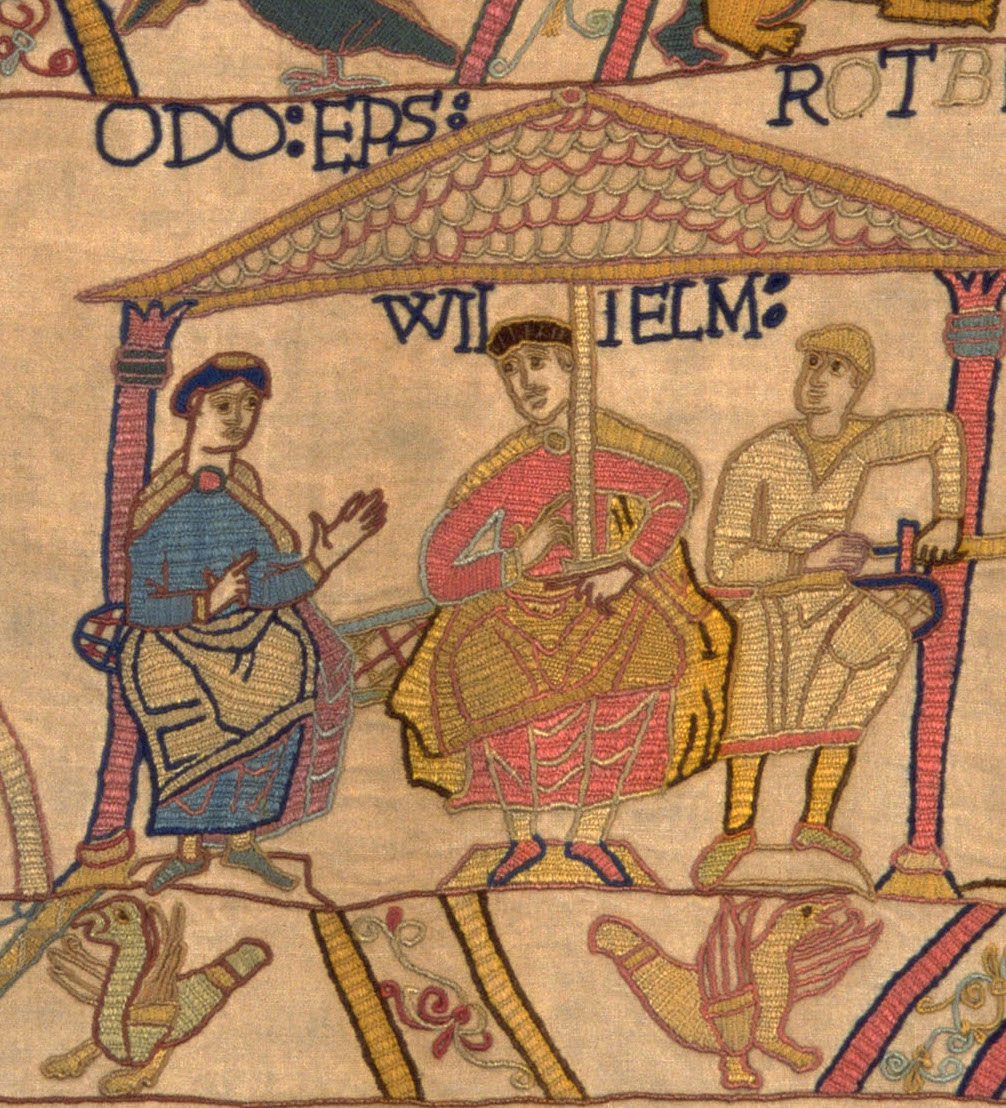

Bishop Odo

Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux, plays a prominent role in the Tapestry, even appearing amidst the fighting at the Battle of Hastings itself.

Bishop of Bayeux

Odo's father was Herluin, Viscount of Conteville. His mother was Herleva, who was also the mother of Duke William of Normandy. When Odo was only nineteen-years-old, William made him Bishop of Bayeux, where he built a cathedral.

When William was planning to invade England, he had Odo at his side. Odo accompanied the Norman army, and as well as leading the prayers for victory, he even fought in the battle, wielding a mace rather than a sword. Although men of the church were not allowed to spill blood, they were permitted to batter their opponents with a club.

Odo was made Earl of Kent and often ruled England when William was in Normandy. He was given great areas of land and he granted some of these areas to his knights. The tapestry may have been made in England to record the Norman victory and Odo's role within it. The tapestry was later hung in Odo's cathedral in Bayeux.

By 1082, William and Odo had fallen out. Odo was imprisoned in Rouen, and was only released shortly before William's death. He then returned to England and plotted against William Rufus, William the Conqueror's son, but was he captured and banished to Bayeux.

Odo died in Sicily in 1097, whilst participating in a crusade to the Holy Land.

Stigand

Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury at the time of Harold's ascension to the throne, had a long career within the church, but his prospects became extremely limited after the Norman invasion, and he was ultimately deposed and imprisoned.

Archbishop of Canterbury

Before the events told by the Tapestry, Stigand had led a long career in the Anglo-Saxon church, first appearing in the historical record in the 1020s as a royal chaplain to King Cnut.

Within the Tapestry, Stigand is portrayed as playing a prominent role at Harold's coronation. Because his appointment as Archbishop was disputed by the Pope, this may have been a Norman attempt to discredit Harold's kingship.

Whilst he initially served in William's new court, Stigand soon fell out of William's favour. In 1070, he was deposed and imprisoned, and he died as a prisoner in Winchester in 1072.

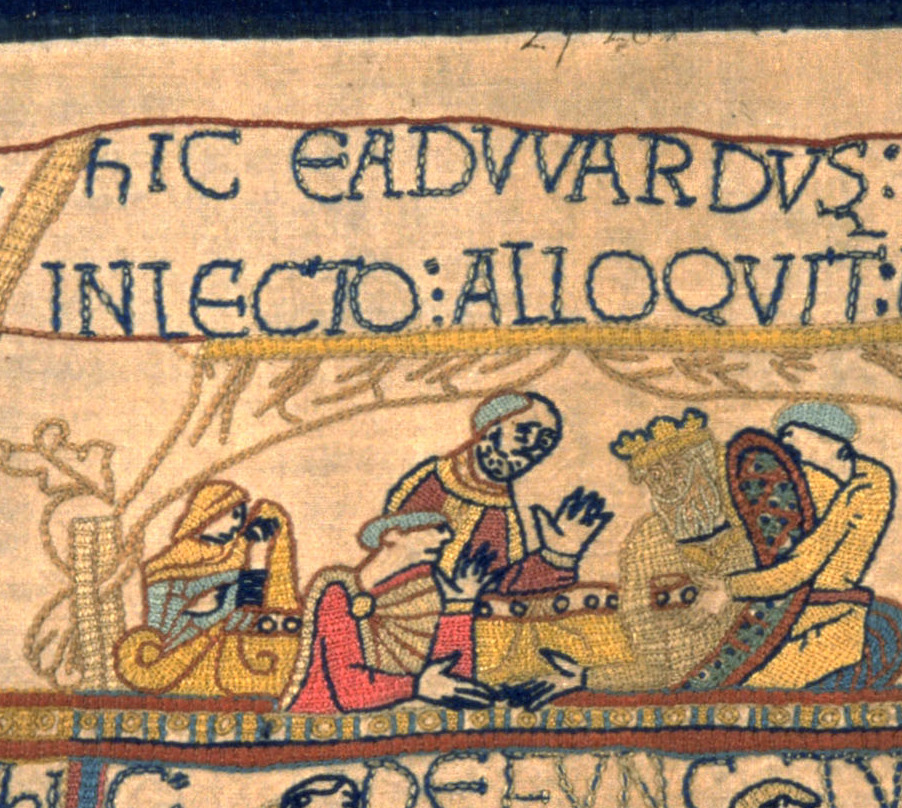

Edith

Edith Godwinson or Edith of Wessex was Harold's sister and Edward's wife. This is probably her (far left) at Edward's death bed.

Only three women appear in the main narrative of the Bayeux Tapestry.

This figure must be Edith (c.1025-1075), the wife of Edward the Confessor and the sister of King Harold.

The author of the Life of St Edward the Confessor, a thirteenth century Anglo-Norman text, records that Edith was present at Edward's deathbed. At that point, Edward commended her to Harold's protection.

Fleeing woman

A woman flees from a burning building.

This woman is shown either trapped inside or fleeing from a burning building at Hastings, when William's troops were harrying the area.

Aelfgyva

Despite its prominent position with the Tapestry, the events behind this scene are unknown today.

The meaning of this scene is obscure but it must refer to a well-known event to be in such a prominent position within the Tapestry.

Aelfgyva was a widely used Saxon name.

The embroiderers of Reading's Victorian copy

Elizabeth Wardle (1834–1902) was an accomplished embroiderer and had founded the Leek Embroidery Society in 1879. Her husband, Sir Thomas Wardle (1831–1909) was a wealthy and successful textile dyer and printer. Elizabeth and Thomas saw the embroidery on a visit to Bayeux in 1885. They were friends of William Morris and shared his interest in the revival of ancient craft skills and the use of natural materials. They also knew Sir Philip Cunliffe-Owen, Director of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) where there was (and still is) a full set of hand-coloured photographs, taken in 1871, of the Bayeux Tapestry. It was after seeing these that Elizabeth developed the idea that she and her friends should make a full-size replica ‘so that England should have a copy of its own’.

As well as members from Leek, women from Derbyshire, Birmingham, Macclesfield and London took part in creating the copy. Each embroiderer stitched her name beneath her completed panel. Elizabeth Wardle added the final inscription at the end of the tapestry in Whitsuntide 1886.

The women who created Reading's copy were:

Miss Alice Allen

Miss Emily A. Bate

Miss Emma Bentley (Leek)

Miss Mary Bishop

Miss Ann Cartwright

Miss Mabel Challinor

Miss Ann Clowes

Miss Elizabeth Eaton (Etwall, Derbyshire)

Miss Elizabeth Frost (Derby)

Miss Mary Alice Garside

Miss Patience E. Gater

Miss M.H. Gillett (Duffield, Derby)

Mrs Mary Adeline (Charles) Gwynne

Miss Elizabeth Haynes

Miss Sarah Iliffe (Edgbaston, Birmingham)

Miss Beatrice Lavington

Mrs Anne Mills Lowe

Mrs Elizabeth V. Lunn (Derby)

Miss Lizzie Mackenzie (Cheadle, Staffs)

Miss Emily Parker

Miss Alice Pattinson (Macclesfield)

Miss Florence Pattinson (Macclesfield)

Miss Florence M. Pearson (Putney, London)

Miss Margaret J. Ritchie

Miss Anne Smith (Endon Bank)

Mrs Jennie (Charles) Smith

Miss Mary E. Turnock

Miss Edith Wardle

Mrs Elizabeth Wardle

Miss Ellinor Wardle

Miss Margaret W. Wardle

Miss Phoebe Wardle (Cheddleton Heath)

Mrs Margaret E. Watson

Mrs Mary Edith Watson

Mrs Margaret Maude Worthington

Lizzie Allen (Mrs Coombe) prepared all the drawings, which were based on coloured drawings lent by the South Kensington Museum. Mrs Clara Bill joined all the sections together.