Written by Dr Cynthia Johnston, lecturer in History of the Book, School of Advanced Studies, University of London.

In the Middle Ages, scribes had to produce readable text within a small amount of space. Parchment was an expensive commodity and commercial scribes not located in monasteries needed to be paid for their services. We cannot be sure where any section of Harley 978 was produced, or who chose the texts gathered together here. We can observe, however, conventional methods used by scribes to make the texts they produced accessible to their readers.

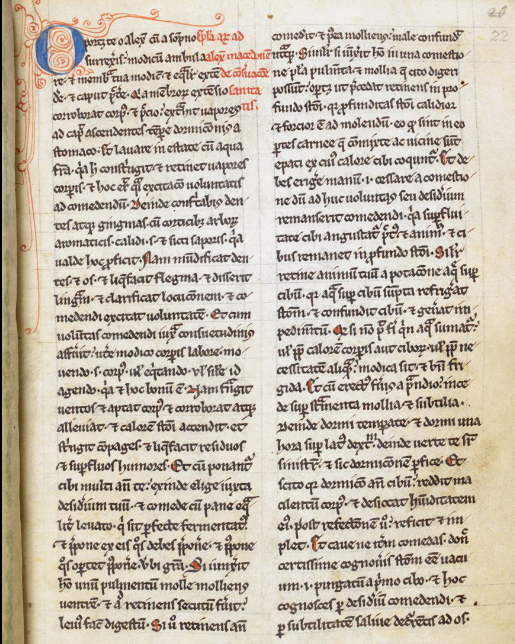

The Secret of Secrets (folio 22r)

This section of Harley 978 contains a miscellany of medical texts which needed various layouts to communicate their contents. Folio 22r opens with the first section of one of the most famous texts of the later Middle Ages: the Secret of Secrets, the Secretum Secretorum.

This opening text claims to be a letter by the famous Greek philosopher, Aristotle, providing health advice for his pupil, Alexander the Great. The letter was accepted as genuine in the medieval period and was specially chosen for translation by a cleric and academic now known as John of Seville. John presented his Latin version to Queen Theresa, who ruled in Portugal from 1112 to 1128.

The first complete translation of the book was made c. 1230 from an Arabic work known as Kitab sirr al-asrâr. It became enormously popular because of its mistaken identification as the fabled book that Aristotle had written for Alexander on the art of governance. The text was reputed to contain Aristotle’s disputations on a wide variety of subjects, but with a special focus on how to live well intended for his inner circle of readers alone. The inclusion of a wide variety of subjects, including hygiene, astrology and alchemy, made it especially popular with medical students and professionals. Some versions included guidance on palmistry and on how to deduce both secret strengths and failings from details of a person's appearance.

This folio opens with a penflourished capital ‘O’ in blue ink, filled and surrounded by swirls of red penflourishing. These embellished capitals marked the beginnings of major passages in the text. The words, ‘Oportet te o Alexander cum a sompno’ ('You ought, o Alexander, with a dream…'), are conventionally abbreviated following medieval scribal practice. The red or rubricated text at the right-hand edge of the text provides a short title in abbreviated form, ‘Aristotle’s letter to Alexander of Macedonia on the conservation of health’. This rubricated text made each section of the book immediately identifiable. The scribe has also marked the beginning of each sentence with a red infill to the first letter. This made the text easier to navigate, especially for study and consultation.

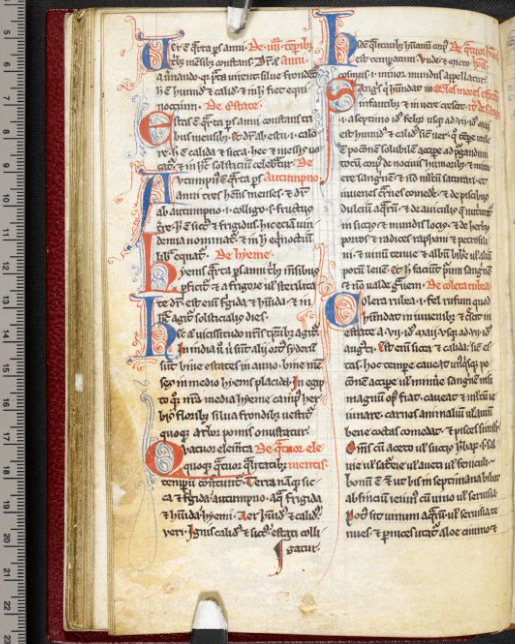

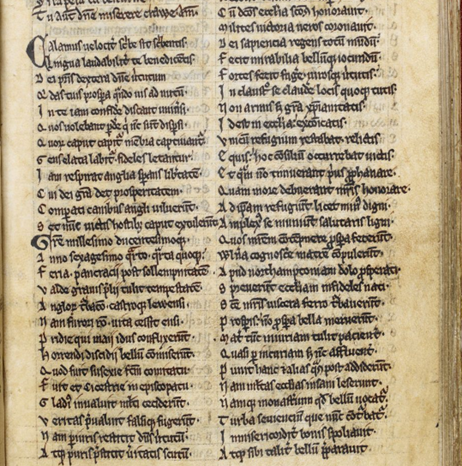

The Secret of Secrets (folio 24v)

This folio is written by the same scribe who used penflourished capitals to indicate separate sections of folio 22r. The subjects featured here in the left-hand column are the four seasons, the four elements (earth, wind, fire and water) and, in the right-hand column, the four bodily humours (sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric and melancholic). The short titles continue to appear in red in the right-hand top corner of each section, and the use of the penflourished initials is intended to make it easy to find what you want to consult on the page. Although the page looks highly decorative to us, the alternating blue and red of the initials and their contrasting flourishing was meant to speed up the medieval reading experience. This indicates the way in which those who commissioned this book expected to use it.

Folio 75r

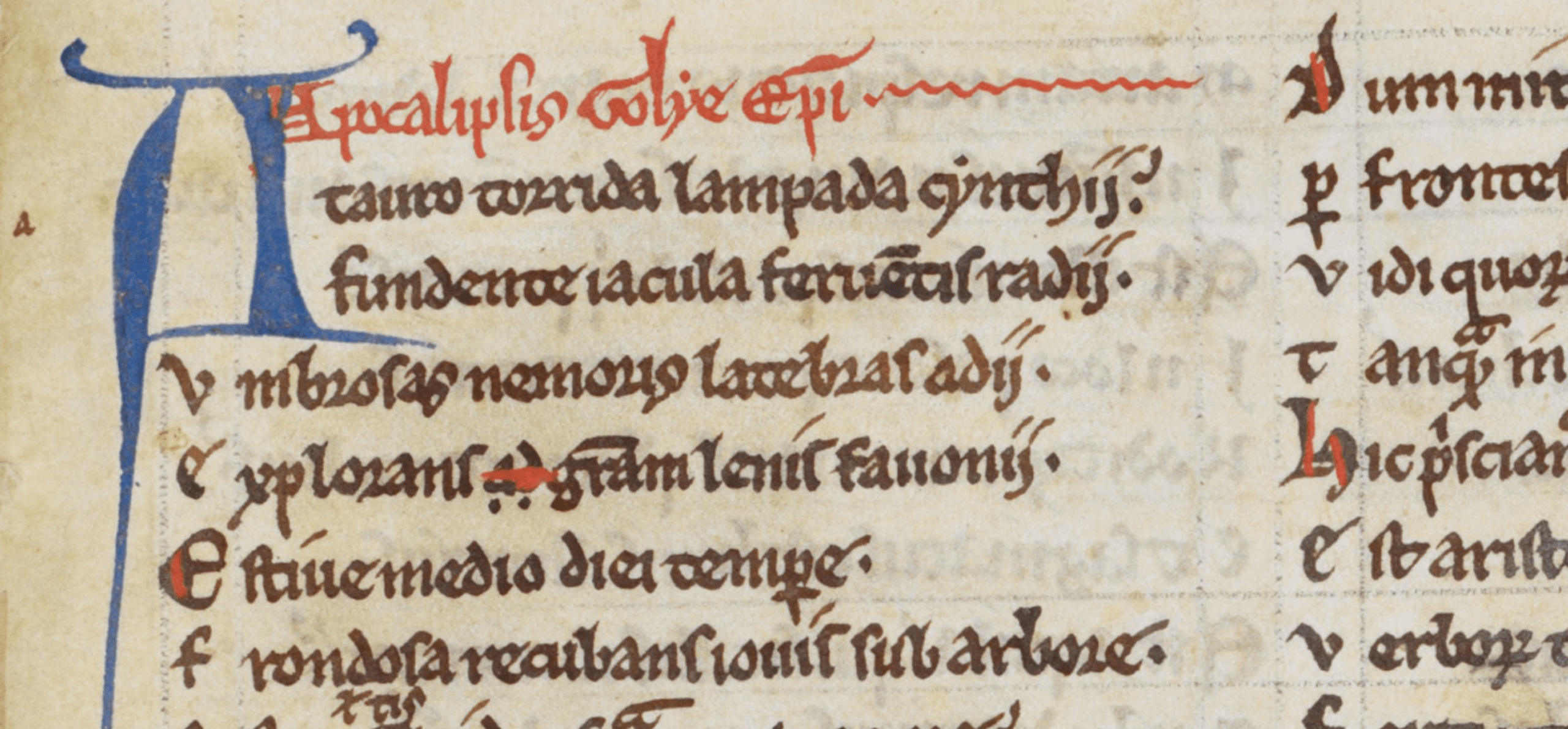

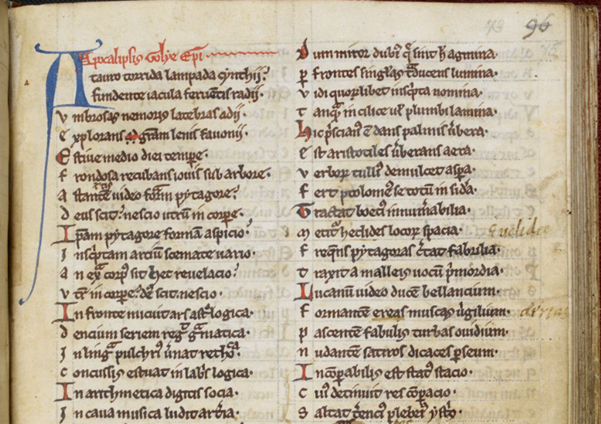

This folio is part of a section containing poetry, which necessitates a completely different lay out of the page. The title of the poem, Apocalipsis Golye episcopi, is rubricated at the top of the page with an elongated capital letter in blue ink. The scribe uses many of the same methods observed in the presentation of the pseudo-Aristotelian material above, but for a very different purpose.

For this poem, the scribe’s repertoire of rubrication and flourishing distinguishes verses and pauses via punctuation, with visible lines, ruled in lead, separating each line. The aim of the scribe was to facilitate continuous reading of the text from start to finish. It may be that oral delivery was anticipated. The first letter of each four-line verse is rubricated to aid the understanding of the structure and the meaning of each section. No doubt delivery of the humour of the verse was suggested by this visual apparatus. The words are still highly abbreviated suggesting that the reader would have been a fluent reader of medieval Latin.

The author of this poem was traditionally assumed to be Walter Map (c.1140-c.1210), who was a courtier in the court of Henry II. Reportedly born in the Welsh Marches, Map trained as a cleric at the University of Paris. He had a successful career as both a diplomat in Henry’s service, and in the church. He rose to be archdeacon of Oxford, but his dream of becoming bishop of Saint David’s remained unfulfilled. Map was a well-known writer of comic verse but is unlikely to be the author of this poem. The poem is in the satirical ‘Goliardic’ tradition of Latin poems which lampooned the conduct of the clergy. The poems were written by disaffected clergy themselves. The origins of the term Goliard are obscure, but it may be associated with the eponymous fictive author of this poem, one Bishop Golias. The name Golias may be suggestive of the biblical giant Goliath.

This poem (The Apocalypse of Bishop Golias) takes the form of a dream vision, with an angel acting as guide. He provides highly uncomplimentary and crudely humorous comparisons of the pope, bishops and other high-ranking churchmen to a variety of unpleasant animals.

Folio 107r

This folio presents another Goliardic poem, the Song of Lewes (or the Song of the Barons). There appears to be a different scribal hand at work here whose writing is more compressed. The verses of this poem are not demarcated by rubrication of the first letter in each verse, and the poem is less elegantly set out. This may have to do with the time available to the scribe or the preference of the original patron of the manuscript. Nonetheless, the scribal hand is professional and confident.

The Song of Lewes celebrates the victory of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, over Henry III, at Lewes on 14th May 1264. The king and his son, the future Edward I, were taken prisoner during the battle. The poem is strongly in favour of the cause of Simon and the other rebels, and was probably copied here before Simon’s death at the Battle of Evesham in August 1265. The poem narrates the battle itself and then reflects on kingship and good governance.

While de Montfort is remembered for supporting a broadening of representation in Parliament, and insisting on adherence to the Magna Carta, his campaign was also marked by antisemitic rhetoric. He sought to absolve himself and others from repayment of debts owed to Jewish creditors. His incendiary rhetoric resulted in massacres of Jewish communities, particularly in London.